Fungi Flourish Below the Seafloor

Searching for life in the deep sea, scientists find surprises

Scientists have discovered a previously unknown diversity of fungi living far beneath the seafloor throughout the world’s oceans.

“Walking in a forest, everyone knows how important fungi are on land in decomposing fallen trees, leaves, and other material,” said William Orsi, a postdoctoral fellow at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “But nobody knew whether fungi performed a similar function in deep subseafloor ocean sediments. Our study shows that fungi are also very important in the subseafloor in a similar way”—breaking down organic matter into nutrients and carbon dioxide that other organisms need and use.

The study, published Feb. 15, 2013, in PLoS One, also produced another unexpected finding: evidence in seafloor sediments for living cells from organisms that usually live near the sea surface. Either the cells were still alive, perhaps in a quiescent form such as a spore, seed, or cyst; or scientists will have to reevaluate the validity of a method they have traditionally used to detect the presence of living organisms in various habitats.

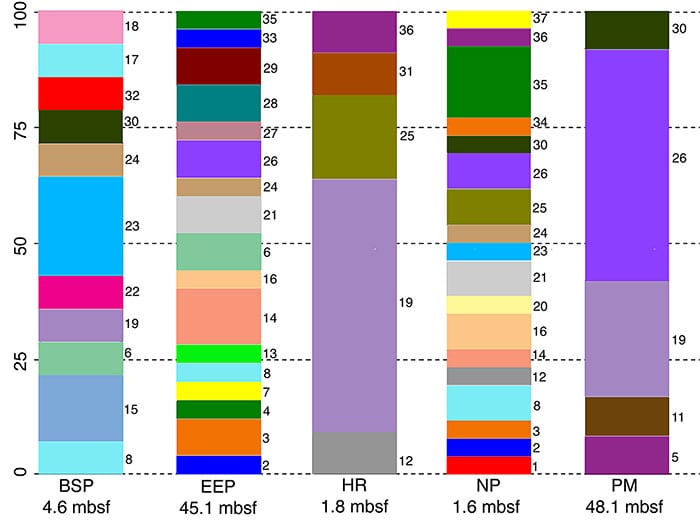

Orsi and his colleagues, microbiologists Virginia Edgcomb of WHOI and Jennifer Biddle of the University of Delaware, identified at least 70 kinds of fungi in sediments collected from six sites around the world at different depths from the surface and different subseafloor conditions. Samples came from depths of 1.8 meters (nearly 6 feet) to 48.1 meters (nearly 158 feet) below the seafloor.

To show that the fungi in the sediments were alive, the scientists analyzed the samples for ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA), which living cells use to produce proteins. Because rRNA normally degrades within hours of a cell’s death, scientists routinely use its presence as proof that the organism it came from is still alive.

The researchers used a recently developed technique (called 454 pyrosequencing) to detect rRNA sequences for up to 75 percent of the fungal species present in samples, compared to only 5 to 10 percent detectable by earlier methods.

“We were able to sequence much more deeply into subseafloor rRNA than had ever been done before, “ said Orsi. “That allowed us to find some rare things that had been missed in earlier studies.”

In addition to identifying rRNA from many more species of fungi than had been found there before, the scientists also found rRNA from organisms that should not be living in deep sediments. For example, all of the samples contained rRNA from diatoms, a type of phytoplankton. Diatoms live near the sea surface, where they can obtain enough sunlight to power their photosynthetic machinery.

After diatoms die, their hard shells may fall to the seafloor and become buried and preserved in sediment. (In fact, scientists use some species of diatom shells to estimate the age of sediments they are found in.) But seafloor sediments should not contain living diatoms.

Finding rRNA from diatoms thus posed a challenge for Orsi and his colleagues: If the rRNA of diatoms was persisting that long in the subseafloor, then perhaps the fungal RNA they found also came from dead organisms.

“We had to come up with some kind of evidence that these fungi are alive and the other guys aren’t alive,” said Orsi. In further investigations, they found that fungal rRNA sequences strongly correlated with organic carbon, a food source for fungi, and with inorganic carbon (mostly carbon dioxide), a waste product of fungal respiration. By contrast, rRNA from diatoms and other groups that should not be living in the sediments were not related to the amount of organic or inorganic carbon in the habitats in which they were found.

The scientists had taken rigorous steps to ensure that the seafloor sediment samples were not contaminated by outside sources, so why rRNA from diatoms was found deep below the seafloor remains a mystery. Orsi said he and colleagues are now conducting experiments to distinguish between two possibilities: Either cells containing rRNA remained alive buried in sediments, perhaps in a dormant form; or their rRNA had persisted long after their death and long after scientists expected it would. If the latter, scientists will have to reevaluate how they interpret rRNA to determine the presence of living organisms.

This research was funded by the Center for Dark Energy Biosphere Investigations and by the Ocean Life Institute at WHOI.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- WHOI postdoctoral fellow Bill Orsi led a team of researchers who identified more than 70 kinds of fungi living in ocean sediments as far as 48 meters (157 feet) below the seafloor. (Photo courtesy of Bill Orsi, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Bar graphs show that ocean sediments from five sites around the world are home to different kinds and numbers of fungi. Each bar represents a sample from one site. The colored and numbered strips on the bars represent different species of fungus. The bigger the strip, the more of that kind of fungus was in the community. Nutrient-rich sediments near coastlines (first, third, and fifth bars) had relatively few fungal species. Nutrient-poor sediments in the deep ocean (second and fourth bars) had more diverse fungal communities. Numbers along the bottom show the depths of each sample, in meters below sea floor (mbsf). Numbers along the left side of the graph show the percentage of the total fungi. BSP=Banguela Upwelling System. EEP=Eastern Equatorial Pacific. HR=Hydrate Ridge. NP=North Pond near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. PM=Peru Margin. (Courtesy of Bill Orsi, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Bill Orsi (left) and his postdoctoral mentor, WHOI microbiologist Virginia Edgcomb (right), look for and analyze microscopic organisms living in extreme habitats, such as deep sediments, hypersaline pools, and anoxic (oxygen-free) areas of the ocean. Here, they work on an instrument designed to sample, incubate, and preserve microbes from specific depths in the ocean. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Orsi and his colleagues analyzed samples from sediment cores similar to this one. Cores are collected by driving long pipes deep into the sediments, then withdrawing them with sediment inside. Back in the lab, each pipe is split down the middle, giving researchers access to the interior of the core. The age of a particular sample is determined in part by measuring its distance from the top of the core (which was at the seafloor). Other methods used to date samples include radiocarbon dating and assessing the microfossils embedded in the sediments. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- Our eyes on the seafloor

- Bridge-to-PhD program at WHOI opens doors for new scientists

- A coral reef kickstart

- Junk Food

- A Lobster Trap for Microbes

- The Unseen World on Coral Reefs

- The Recipe for a Harmful Algal Bloom

- The Bacteria on Your Beaches

- Scientists Reveal Secrets of Whales

- In the Gardens of the Queen

- The Amazing Acquired Phototroph!

- What Happened to Deepwater Horizon Oil?

- New Device Reveals What Ocean Microbes Do

- Life Dwells Deep Within Earth’s Crust

- Can Animals Live Without Oxygen?

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Virginia Edgcomb's lab

- Integrated Ocean Drilling Program The IODP collects sediment cores that can be used by scientists at many institutions. It provided many of the samples used in this study.

- Deep Marine Subsurface Eukaryotes Summary of the Edgcomb lab's work with sediment microbes.