Cold Comfort for Barnacles

Researchers are surprised to find that frozen barnacle larvae can revive

Cast adrift in coastal oceans, the tiny, weakly swimming larvae of marine animals such as barnacles must employ the ocean’s currents and tides—and also avoid obstacles including predators—to arrive at a place where they can mature into adults. Ice was always thought to be one of the obstacles, and a larva that didn’t settle down before winter set in was considered a goner.

But in the winter of 2003, Claudio DiBacco, a postdoctoral investigator, and Research Associate Vicke Starczak, both working with WHOI marine ecologist Jesús Pineda, were taking samples of seawater along the Rhode Island shore and found barnacle larvae frozen into sea ice. They placed them in water, where they revived and swam normally.

The intriguing finding detoured Pineda’s lab group into a new series of lab and field experiments. He and colleagues (some from the warm climates of Spain and Chile), and two local high school students worked in icy conditions from January to May, tracking thousands of larvae in coastal sites from Rhode Island to Nova Scotia. In the September 2005 issue of the journal Limnology and Oceanography, the team reported that barnacle larvae can remain frozen up to seven weeks and still revive, settle, and grow to reproduce.

“We tend to have an anthropocentric view of larvae as babies that don’t tolerate severe conditions,” Pineda said, “but it isn’t always true.”

The discovery offers a new understanding of barnacle larvae, which are abundant sources of food for larger animals in the coastal ocean. It also provides possible clues to how other northern intertidal marine invertebrates may settle and survive harsh winters.

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Slideshow

Slideshow

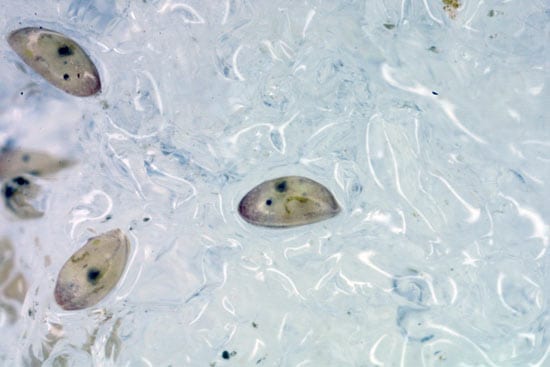

- WHOI researchers found these barnacle larvae, called cyprids, frozen into ice in January on the shores of Buzzards Bay, Mass. They were surprised to find that the larvae (at 1 millimeter long, about half the diameter of the head of a pin) could thaw out, swim, and develop into normal adults. (Photo by Jesús Pineda, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Carolina Cartes, a visiting investigator from Chile working with WHOI biologist Jesús Pineda, looks for tiny larval barnacles in the icy intertidal zone along the northeast U.S. coast during winter. (Jesús Pineda, WHOI)

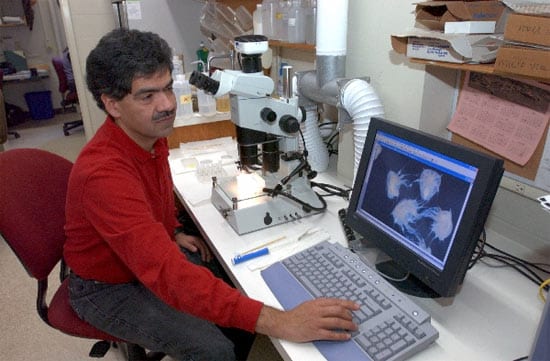

- Biologist Jesús Pineda studies how ocean currents and tides carry tiny larvae of coastal invertebrates such as barnacles from their places of origin to other sites where they can settle to the bottom and mature into adults. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, WHOI)