Alvin Gets an Interior Re-design

Sub's new sphere offers room to add a bit of comfort

For more than four decades, scientists have foregone a few creature comforts to see animals, or volcanoes, or shipwrecks at the bottom of the sea.

On a typical dive in the research submersible Alvin, a pilot and two scientists climb through a narrow hatch into an equipment-filled, 6-foot-diameter titanium sphere. Once sealed inside, they have no room to stand up, no seats, and no bathroom. For up to eight hours, they sit on thin pads on the floor and peer out windows, or viewports, the size of teacup saucers. The pilot drives while perched on a small metal box.

“It sort of equates to sitting in a phone booth with two of your closest friends, all day long,” said Patrick Hickey, Alvin operations manager at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), who has logged 636 dives as the sub’s pilot.

“Being on the smaller side is definitely a plus when you dive in Alvin,” said Bruce Strickrott, who, at 6 feet 3 inches, is currently Alvin’s tallest pilot.

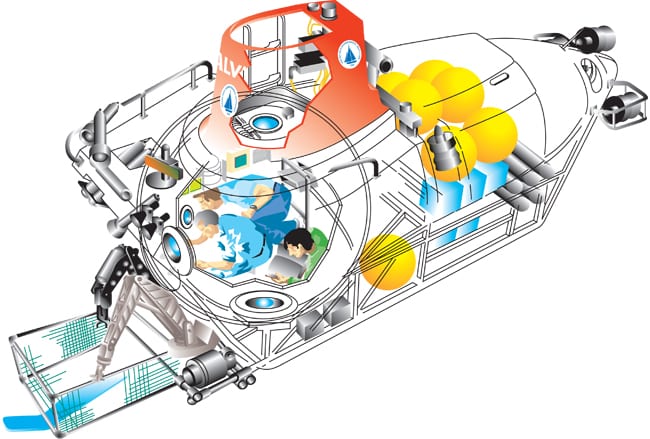

But now engineers at WHOI have begun planning a multimillion-dollar overhaul that will ultimately allow Alvin to stay down longer (up to 12 hours) and dive deeper (6,500 rather than 4,500 meters). To withstand greater pressures at greater depths, a new, stronger titanium sphere has been forged . It is 3, rather than 2, inches thick, with an interior diameter that is 4.6 inches wider than Alvin’s current sphere. That increases the interior volume by 18 percent, from 144 to 171 cubic feet, and that additional space has opened up a range of new possibilities.

“The buzzword is ergonomics,” said Anthony Tarantino, a former Alvin pilot. He is part of a team of marine engineers at WHOI who have donned the hats of interior designers to make Alvin, a workhorse of the oceanographic community, a little more comfortable.

Space constraints

Even before thinking of a redesigned interior, engineers on the project considered the shape and weight of every item that must fit inside the submersible on each dive. All told, the list includes about 300 items. Every power, navigation, and alarm system panel, storage shelf, camera control device, ethernet switch, emergency flashlight, and even the pilot’s small seat must be weighed to ensure that Alvin has enough buoyancy material to keep the submersible upright and stable during a dive.

Once all the equipment is inside, what space remains goes to the pilot, the scientists, and the small bags of items that they bring down with them (typically, a snack, notepads or other recording devices, and extra warm clothing).

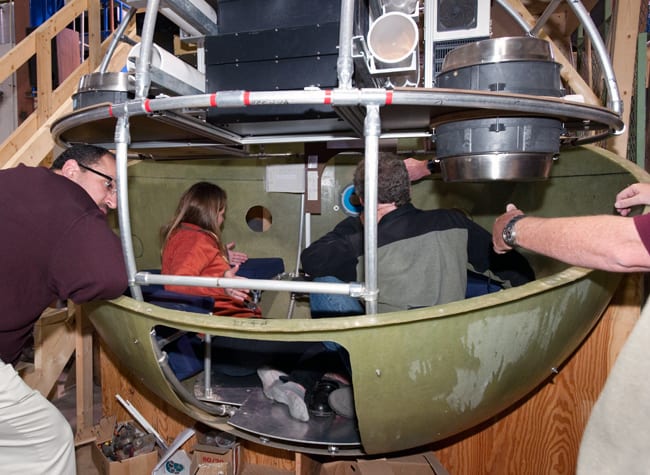

Fitting it all inside the sphere is like piecing together an enormous puzzle inside a big ball. In a laboratory on a dock in Woods Hole, engineers created a prototype fiberglass version of the new sphere to give people a sense of the available space and help them figure out where everything might go.

To represent each item that will go into the sphere, engineers designed and built cardboard mock-ups of computer monitors, video displays, handheld cameras, and dozens of other pieces of equipment to help work out how to fit people and components harmoniously together.

In spring 2010, Chris German, chief scientist for deep submergence at WHOI, distributed a 20-question survey to Alvin users, seeking their opinions on changes they would most like to see in the new sphere’s interior. More than 110 biologists, geologists, microbiologists, geochemists, and engineers responded.

Seats, sights, and heights

The survey also asked people about their height and vision. German said the information will help make the interior set-up of the sphere more user-friendly, and when possible, adjustable to accommodate different needs.

Half of the respondents reported that they are nearsighted. “During the average dive, people are constantly looking out of a viewport then back to a computer screen or notepad to record what they are seeing, or to interior video screens showing live video feeds to areas around the submersible,” German said. “It means they are constantly refocusing their eyes. That’s important to know because it helps us decide where we are going to put key components like video monitors,” especially in relation to where scientists will position themselves inside the sphere.

As to how they will position themselves, scientists will have more options. The new locations of the viewports necessitated changes in seating, which gave engineers an opportunity to build in some more comfort. Now, passengers often sit on the floor, with their heads on opposite sides of the sphere and their legs poking into shared space in the center, trying not to kick each other or the pilot’s metal box seat. To get people off the floor, engineers have proposed adjustable benches that allow passengers the choice of kneeling, sitting, or lying flat.

Built for depth, not for comfort

With such an expensive and carefully crafted investment, why not make the new sphere really snazzy by adding reclining leather seats? a reporter suggested. How about a few cozy cashmere blankets and an Italian coffee maker, which would fight the chill that comes from the average temperatures of 55° to 65°F inside the sphere? Tarantino laughed and shook his head.

Weight limits prohibit too many frills, he said. Safety considerations also add constraints. To prevent a fire inside the submersible, electronics must meet strict criteria before they are allowed in. Fabrics covering the foam pads also must be fire-resistant and made from a material that would not emit noxious fumes.

“We’re never going to be able to provide luxury,” said German. “It’s not like flying business class.”

But lack of comfort is part of the experience, he said. Sharing a ride in Alvin bonds people, he said, in the same way that people sometimes feel a shared experience after making an arduous car journey.

“People know that they have endured one of the more uncomfortable rides on Earth to be a part of a really special group,” German said.

Hickey, Alvin’s operations manager, was confident that people would enjoy improved creature comforts in the new sub. But he forewarned future passengers that they still won’t find one thing on board: indoor plumbing.

Funding to upgrade the submersible comes from the National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences and and private donations to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- On a typical dive in the research submersible Alvin, a pilot and two scientists crowd into a 6-foot-diameter personnel sphere in the front of the sub. (Illustration by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

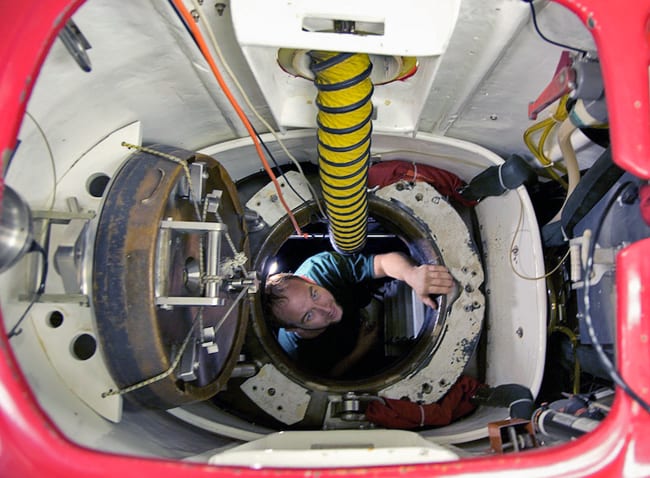

- People descend through a narrow hatchway into Alvin's personnel sphere, where WHOI engineer Jeff McDonald is standing and looking up. Once sealed inside, they have no room to stand up, no seats, and no bathroom. (Photo by Buffy Cushman-Patz, Teacher at Sea)

- Last year, the process began to create a new, larger personnel sphere for Alvin. Massive titanium ingots, weighing a total of 34,000 pounds, were heated and reshaped into two giant hemispheres that were machined and welded together. (Photo courtesy of the Advanced Imaging & Visualization Laboratory, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The new sphere will have five, rather than, three viewports; three will be 7, rather than 5, inches in diameter. To withstand pressures at greater depths, the sphere will be 3, rather than 2, inches thick, with an interior diameter that is 4.6 inches wider than Alvin’s current sphere. That increases the interior volume by 18 percent, from 144 to 171 cubic feet. (Illustration by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Members of a scientific advisory committee for national deep-submergence vehicles test a mock-up of the new Alvin sphere constructed by engineers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The scientists offered feedback on ways to make the sphere more comfortable and effective. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A preliminary view of the upgraded submersible, when the new personnel sphere and other additions are in place. (Illustration by Megan Carroll, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- The story of a “champion” submersible

- Robots to the Rescue

- Who is Alvin and what are sea trials?

- 7 Places and Things Alvin Can Explore Now

- The story of “Little Alvin” and the lost H-bomb

- Meet the Alvin 6500 Team: Lisa Smith

- Overhaul to take Alvin to greater extremes

- Meet the Alvin 6500 Team: Rose Wall

- Racing an undersea volcano

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Human-Occupied Vehicle Alvin Alvin is a 3-person research submarine that takes scientists deep into the ocean. Since its launch in 1964, the Alvin has taken more than 2,500 scientists, engineers and observers to visit the floor of the deep sea.

- Building the Next-Generation Alvin Submersible Plan offers roadmap to extend sub's diving capacity to reach 99 percent of seafloor

- Frequently Asked Questions about Alvin from WHOI Ocean Instruments

- Alvin Pilots A tight-knit group with the 'right stuff' to guide a submersible on the seafloor. from Oceanus magazine