A new underwater robot could help preserve New England’s historic shipwrecks

WHOI’s ResQ ROV to clean up debris in prominent marine heritage sites

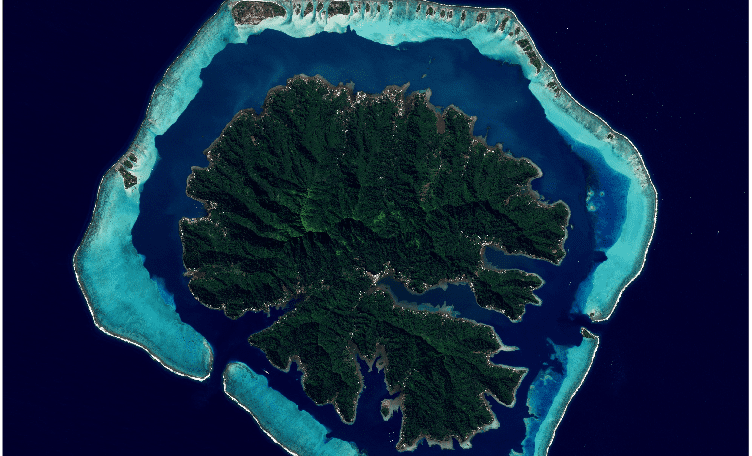

From ruin to reef

What Pacific wrecks are teaching us about coral resilience—and pollution

One researcher, 15,000 whistles: Inside the effort to decode dolphin communication

Scientists at WHOI analyze thousands of dolphin whistles to explore whether some sounds may function like words

Remembering Tatiana Schlossberg, a voice for the ocean

Environmental journalist and author Tatiana Schlossberg passed away after battling leukemia on December…

As the ocean warms, a science writer looks for coral solutions

Scientist-turned-author Juli Berwald highlights conservation projects to restore coral reefs

How an MIT-WHOI student used Google Earth to uncover a river–coral reef connection

Google Earth helps researcher decode how rivers sculpt massive breaks in coral reefs

The little big picture

WHOI senior biologist Heidi Sosik on the critical need for long-term ocean datasets

Lessons from a lifetime of exploration

Award-winning ocean photographer Brian Skerry shares insights from a career spent around ocean life and science

and get Oceanus delivered to your door twice a year as well as supporting WHOI's mission to further ocean science.

Our Ocean. Our Planet. Our Future.

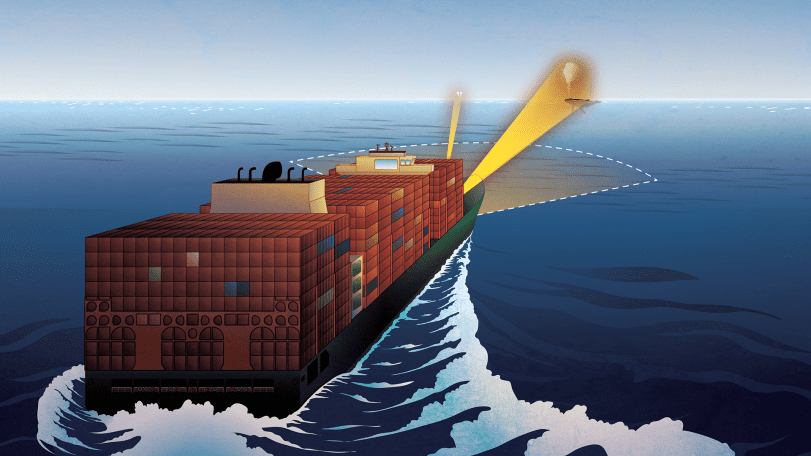

The ocean weather nexus, explained

The vital role of ocean observations in extreme weather forecasting

Breaking down plastics together

Through a surprising and successful partnership, WHOI and Eastman scientists are reinventing what we throw away

Three questions with Carl Hartsfield

Captain Hartsfield, USN retired, discusses the role ocean science plays in our national defense

The Ocean (Re)Imagined

How expanding our view of the ocean can unlock new possibilities for life

Body snatchers are on the hunt for mud crabs

WHOI biologist Carolyn Tepolt discusses the biological arms race between a parasite and its host

A polar stethoscope

Could the sounds of Antarctica’s ice be a new bellwether for ecosystem health in the South Pole?

Secrets from the blue mud

Microbes survive—and thrive—in caustic fluids venting from the seafloor

Looking for something specific?

We can help you with that. Check out our extensive conglomeration of ocean information.

Top 5 ocean hitchhikers

As humans traveled and traded across the globe, they became unwitting taxis to marine colonizers

Following the Polar Code

Crew of R/V Neil Armstrong renew their commitment to Arctic science with advanced polar training

Harnessing the ocean to power transportation

WHOI scientists are part of a team working to turn seaweed into biofuel

Casting a wider net

The future of a time-honored fishing tradition in Vietnam, through the eyes of award-winning photographer Thien Nguyen Noc

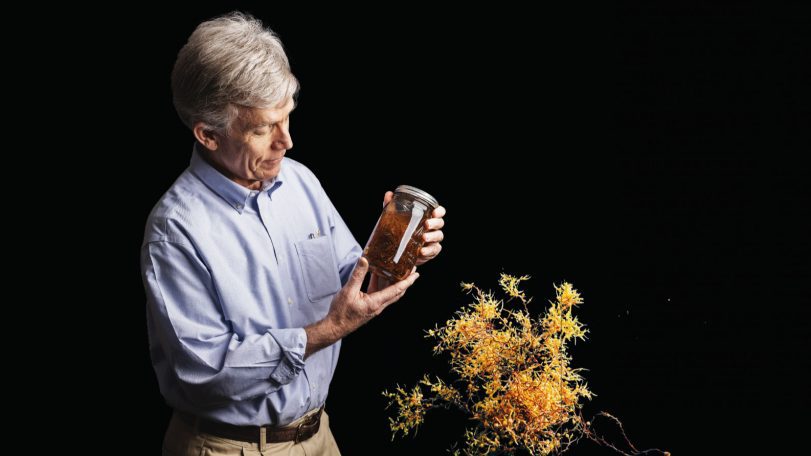

Gold mining’s toxic legacy

Mercury pollution in Colombia’s Amazon threatens the Indigenous way of life

How do you solve a problem like Sargassum?

An important yet prolific seaweed with massive blooms worries scientists

Ancient seas, future insights

WHOI scientists study the paleo record to understand how the ocean will look in a warmer climate

Rising tides, resilient spirits

As surrounding seas surge, a coastal village prepares for what lies ahead

Whistle! Chirp! Squeak! What does it mean?

Avatar Alliance Foundation donation helps WHOI researcher decode dolphin communication

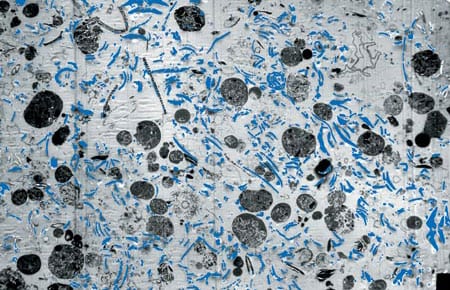

The Rain of Ocean Particles and Earth’s Carbon Cycle

WHOI Phytoplankton photosynthesis has provided Earth’s inhabitants with oxygen since early life began. Without this process the atmosphere would consist of carbon dioxide (CO2) plus a small amount of nitrogen, the atmospheric pressure would be 60 times higher than the air we breathe, and the planet’s air temperatures would hover around 300°C. (Conditions similar to these are found on Earth’s close sibling Venus.

Deploying the Rain Catchers

Deployment of a deep-ocean sediment trap mooring begins with the ship heading slowly into the wind.

Monsoon Winds and Carbon Cycles in the Arabian Sea

The monsoon, a giant sea breeze between the Asian massif and the Indian Ocean, is one of the most significant natural phenomena that influences the everyday life of more than 60 percent of the world’s population.

A New Way to Catch the Rain

The carbon budget of the upper ocean includes an important loss to the deep ocean due to a very slowly falling rain of organic particles, usually called sediment. As this sediment falls through the upper water column it is consumed, mainly by bacteria, and the carbon is recycled into nonsinking forms (dissolved or colloidal organic carbon or inorganic forms). Thus the sediment rain decreases with increasing depth in the water column, and only a tiny fraction reaches the deep sea floor, less than about one percent.

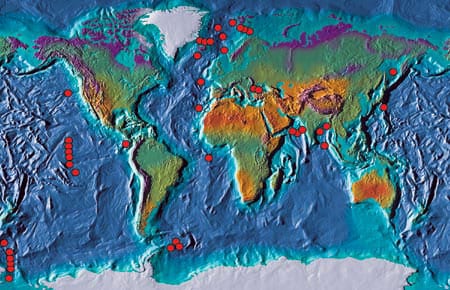

Continental Margin Particle Flux

The boundaries between the oceans and the continents are dynamic regions for the production, recycling, and deposition of sedimentary particles. In general, rates of biological productivity along continental margins are significantly higher than in the open ocean. This is due to a variety of factors including coastal upwelling of nutrient-rich waters and nutrient input from continental runoff. While continental margins account for only about 10 percent of the global ocean area, 50 percent of the total marine organic carbon production is estimated to occur in this limited region, with much of it exported to the deep sea.

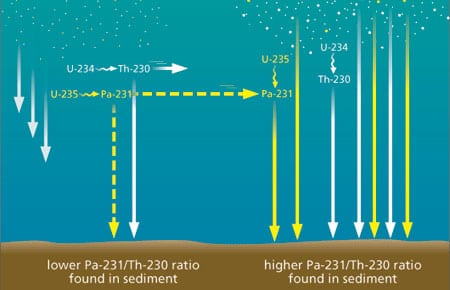

Geochemical Archives Encoded in Deep-Sea Sediments Offer Clues for Reconstructing the Ocean’s Role in Past Climatic Changes

Geochemical Archives Encoded in Deep-Sea Sediments Offer Clues for Reconstructing the Ocean’s Role in Past Climatic Changes

Paleoceanographers are trying to understand the causes and consequences of global climate changes that have occurred in the geological past. One impetus for gaining a better understanding of the factors that have affected global climate in the past is the need to improve our predictive capabilities for future climate changes, possibly induced by the rise of anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere.

Ground-Truthing the Paleoclimate Record

Sediment Trap Observations Aid Paleoceanographers

The geological record contains a wealth of information about Earth’s past environmental conditions. During its long geological history the planet has experienced changes in climate that are much larger than those recorded during human history; these environmental conditions range from periods when large ice sheets covered much of the northern hemisphere, as recently as 20,000 years ago, to past atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases that warmed Earth’s polar regions enough to melt all of the ice caps 50 million years ago. Since human civilization has developed during a fairly short period of unusually mild and stable climate, humans have yet to experience the full range of variability that the planet’s natural systems impose. Thus, the geological record has become an extremely important archive for understanding the range of natural variability in climate, the processes that cause climate change on decadal and longer time scales, and the background variability from which greenhouse warming must be detected

Catching the Rain: Sediment Trap Technology

WHOI Senior Engineer Ken Doherty developed the first sediment trap in the late 1970s for what has come to be known as the WHOI PARFLUX (for “particle flux”) group. Working closely with the scientific community, Doherty has continued to improve sediment traps for two decades, and these WHOI-developed instruments are widely used both nationally and internationally in the particle flux research community.

Replacing the Fleet

When R/V Atlantis arrived in Woods Hole for the first time on a bright, beautiful April 1997 day, it represented not only a welcome addition to the WHOI fleet but also the culmination of a 15-year UNOLS fleet modernization.

WHOI and Access to the Sea

In the mid-term future, two WHOI ships (Knorr in about 2006 and Oceanus in about 2009) will reach the end of their planned service lives. There is general agreement that WHOI should work to replace them with two vessels.

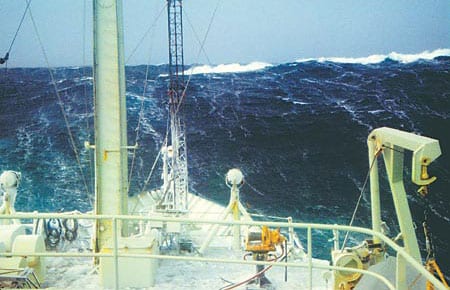

A Northern Winter

As the 1996-1997 ship schedule began to take shape in 1995, we learned that Voyage 147 would take R/V Knorr into the North Atlantic from October ’96 through March of ’97. The various science missions would require station keeping during CTD casts, deployment of current drifters, and expendable bathythermograph (XBT) launches, as well as weather system analysis designed to put Knorr in the path of the harshest weather conditions possible during the winter season. Long before the cruise, we began to tap all available assets that would help us with this challenge.

Adventure in the Labrador Sea

The sound of the general alarm bell reverberated through the ship. At 2:30 AM, this couldn’t be a drill. Even more puzzling, we were still dockside in Halifax, four hours from our scheduled departure for the Labrador Sea.