Students Get Their Sea Legs

Orientation cruise provides introduction to ocean research

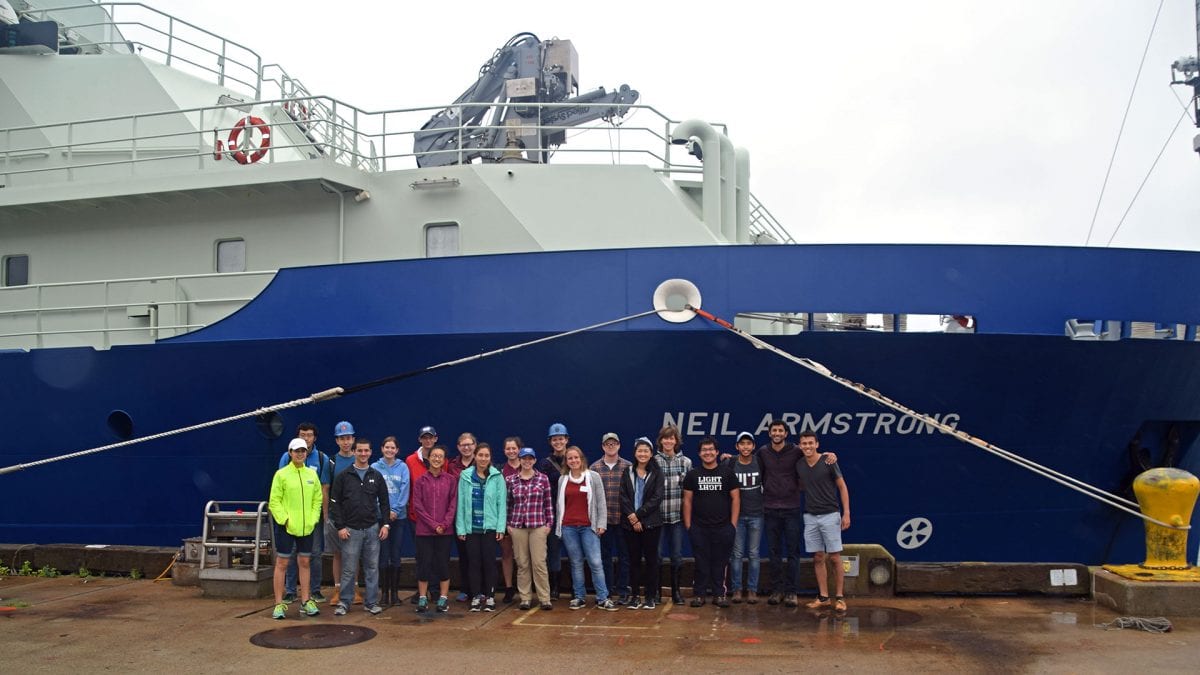

Emmanuel Codillo and Jing He are graduate students at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), which is renowned for its ocean-going research. But like many incoming students, Codillo and He had never set foot on a large research ship until last September, when they joined 14 other first- and second-year students on a 30-hour cruise to the edge of New England’s continental shelf aboard the research vessel Neil Armstrong.

“When I first stepped into it, I was kind of amazed,” Codillo said.

“It was huge and really beautiful!” He agreed. “It was so much nicer than I was expecting it to be.”

Every year, students in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program take a Student Orientation Cruise designed to introduce new graduate students to shipboard life and the basic techniques and equipment involved in oceanographic research. Previous orientation cruises have been aboard the Sea Education Association’s 98-foot-long sailing ship, the SSV Corwith Cramer. But in 2017, WHOI Vice President for Marine Operations and Facilities Rob Munier had the idea of taking students out on the Armstrong.

“We established the Armstrong Endowment with the goal of funding ship time for strictly WHOI use,” Munier said. “This has allowed us, for the first time, to make one of the large WHOI ships available for a student-run oceanographic mission. While raising money for an endowment is not easy, this mission is proof of the tremendous value of such an investment.”

A student-run expedition

When Munier says the cruise was student-run, he means it: WHOI physical oceanographer Glen Gawarkiewicz was nominally the chief scientist, but he wanted students to take the lead. “I think one of the most important aspects of the cruise was that it was entirely student-run,” he said. “It was not tied in to any individual project, so the students really had the intellectual freedom to explore what they thought would be good science questions, in addition to going through the amazing pile of work that happens when you’re a chief scientist.”

Taking on that “amazing pile of work” were Jacob Forsyth and Joleen Heiderich, both physical oceanographers; Kevin Archibald, a biologist; and EeShan Bhatt, who works with acoustics—all third-year graduate students.

“I underappreciated how much time and effort goes into planning a cruise,” Forsyth said. “This probably took Joleen and me a full month of our time, day in and day out.”

There were forms to be collected, certifications to verify, safety gear to check out, and berths to assign—“and, of course, there’s the whole actual planning of what science you’re going to do,” he said.

Science at sea

The plan was for the Armstrong to travel along a transect from Cape Cod, Mass., to the Ocean Observatories Initiative’s Pioneer Array, an installation of moorings and underwater gliders collecting oceanographic data at the edge of the continental shelf, about 80 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard. Along the way, the ship would stop at a dozen sampling locations, or stations, where students would use an instrument called a CTD rosette to measure temperature and salinity of seawater in real time.

“A CTD stands for conductivity, temperature, depth,” Forsyth explained. “It’s probably the most basic equipment that we use in physical oceanography.”

Forsyth and Heiderich also planned to have the students use the ship’s Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler, or ADCP, to measure water velocity; its multibeam sonar to map the topography of the ocean bottom; and its EK80—a multifrequency echosounder—to look for a diversity of organisms beneath the ship.

For some students, the cruise was also a chance to try out equipment outside of their usual field. Both Codillo, who is studying marine geology, and He, who is studying physical oceanography and climate, ended up working in the ship’s lab with an Imaging FlowCytobot, an instrument invented by WHOI biologist Heidi Sosik to take high-resolution images of the ocean’s microscopic life.

“You just stick a little probe into a vial of water, and you get these really beautiful images,” He said. “And I’m not a biologist, so this was all really new and pretty neat to me.”

A top-notch crew

Doing science at sea takes careful coordination between the scientists and the ship’s captain and crew, starting well before a cruise begins. In this case, it was up to Forsyth and Heiderich to work out all the details: to verify the speed of the ship, how long it would take to get to sampling locations, and how much time would be available at each location, for example.

“We emailed a lot with the captain of the ship,” Heiderich said. “Relying on the Armstrong crew and their experience was very important to making this actually work.”

That was especially true on this particular cruise, Gawarkiewicz said, because so many of the students had not been on a research ship before. On a typical cruise, there might be at most one or two people who have limited experience at sea. Having the cruise be both educational and safe was a top priority.

“When you have half the science party that may only have been on a ferry before, it’s a real challenge,” Gawarkiewicz said. “It required a lot of tact and sensitivity and empathy, and my goodness, did the ship ever come through with flying colors.”

Getting a taste for ocean research

For the first-year students, it was a chance get to know the Armstrong crew, to meet their peers in other marine science fields—and to get a taste, literally and figuratively, of shipboard life.

“The food on the ship was just incredible!” He said. She was particularly impressed with “cheese-thirty,” a tradition carried over from the R/V Knorr of serving cheese, crackers, and fruit in the ship’s mess every afternoon at 2:30. “I think the Armstrong set my expectations really high for future cruises.”

But not everything about the cruise happened on schedule, or according to plan. When it comes to doing research at sea, you have to be adaptable—and expect the unexpected.

For one thing, the weather out on the open ocean is always a wild card.

“When we first set out it was really nice, and sunny, and seashells, and balloons,” Gawarkiewicz said. But by midnight, everything looked and felt very different.

“The waves got a lot bigger, and the ship was rocking back and forth,” He said. “We had to secure all the equipment down onto the tables. And I remember at one point, the waves, they kept crashing over the side of the ship, and so we all got really wet.”

To complicate matters, a trawl winch malfunctioned, making it impossible for the night shift to do the net tows that Forsyth and Heiderich had planned—so they had to do some quick thinking.

“We had to readjust our entire sampling plan, and come up with something different,” Heiderich said. “That’s what life on a cruise is like.”

“Things go wrong, and you have to be ready to adapt to that,” echoed Forsyth.

2018 cruise planned

Codillo says he was couldn’t believe how well Heiderich and Forsyth handled everything.

“They are just students!” Codillo said. “But they could manage very well, they were very responsible, and they organized everything smoothly. Organizing a cruise—it’s so much. They were pro.”

“I totally agree!” He said. “There are just so many different moving parts on a cruise, and there’s a lot of puzzle pieces that need to fit together. I think one thing that I’ll be mindful of is just how my part of the puzzle fits into the whole.”

Munier and Gawarkiewicz count the 2017 cruise as a big success. But they say 30 hours was not enough time for the students to really get a feel for the pace and momentum of a research cruise. They have already begun planning for the next one—a three-day expedition this November.

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

- At the start of research cruises, researchers coming aboard must go through safety training. Safety is always a top concern, and it was priority on the Student Orientation Cruise, because so many participants had little or no experience at sea. Preparing for emergencies is no joke—but student Adrian Garcia (right) can't help but crack a smile under the hood of the bulky, bright orange survival gear known as a gumby suit, as Rui Chen (left) and Emmanuel Codillo listen for further instructions. (Joleen Heiderich, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- First-year MIT-WHOI Joint Program student Jing He wears a personal flotation device as part of pre-cruise safety training on the research vessel Neil Armstrong. She had never been on a large research ship prior to participating in the Student Orientation Cruise last September. (Joleen Heiderich, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

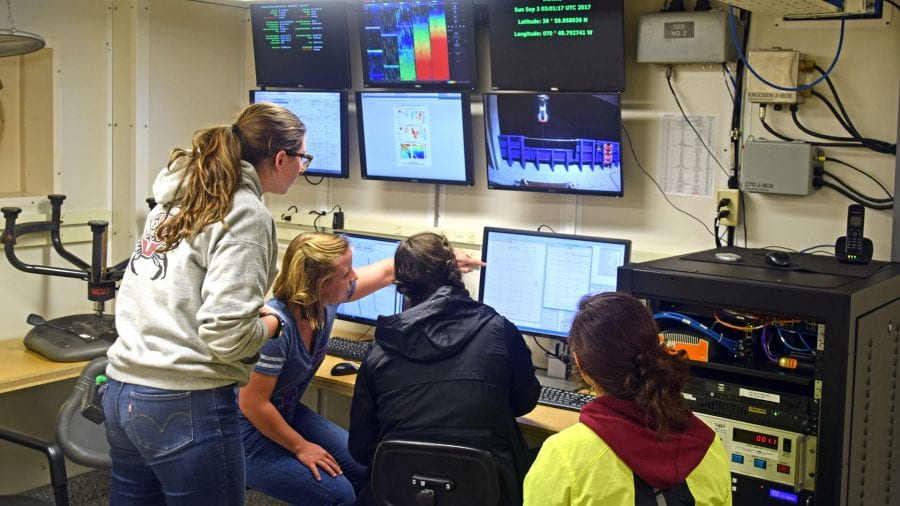

- Third-year graduate student Joleen Heiderich (center left) shows first-year students Ellen Lalk (center right) and Marissa Kellogg (right) and SSSG technician Lauren Kowalski (left) how to read data being relayed in real time from the ship's CTD, an instrument that measures conductivity (salinity) and temperature as a function of depth. Heiderich and fellow third-year students Jacob Forsyth, EeShan Bhatt, and Kevin Archibald planned and led the 2017 WHOI Student Orientation Cruise as its de facto chief scientists, under the supervision of WHOI physical oceanographer Glen Gawarkiewicz. (Rui Chen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

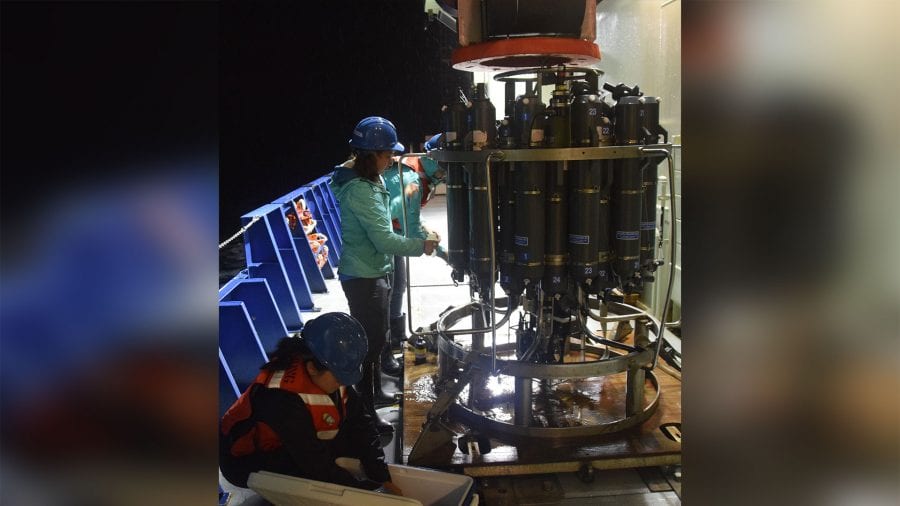

- On a research cruise, work often continues around the clock. Here, students Sheron Luk (left), Fiona Clerc (center), and Julia Middleton work on the night shift with one of the most ubiquitous pieces of equipment in physical oceanography: the ship's CTD. Sensors on the CTD measure conductivity (salinity), temperature, and pressure (depth) as it descends through the water, relaying measurements back in real time to a computer in the ship's lab. On the way back up, sampling bottles can be triggered to close at specific depths to collect water for further chemical analysis. (Rui Chen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Participants in the 2017 WHOI Student Orientation Cruise ham it up for the camera in the main lab of the research vessel Neil Armstrong. Along with providing an experience of life at sea and hands-on training in the basic techniques of oceanographic research, the cruise was an opportunity for the students to get to know their WHOI peers in different subfields of ocean science. (Lauren Kowalski, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI physical oceanographer Glen Gawarkiewicz works in the main lab of the research vessel Neil Armstrong during the 2017 WHOI Student Orientation Cruise. Gawarkiewicz was the chief scientist on the cruise, but he had third-year graduate students take the lead, working with the ship's captain and crew to plan and carry out their research objectives. (Rui Chen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)