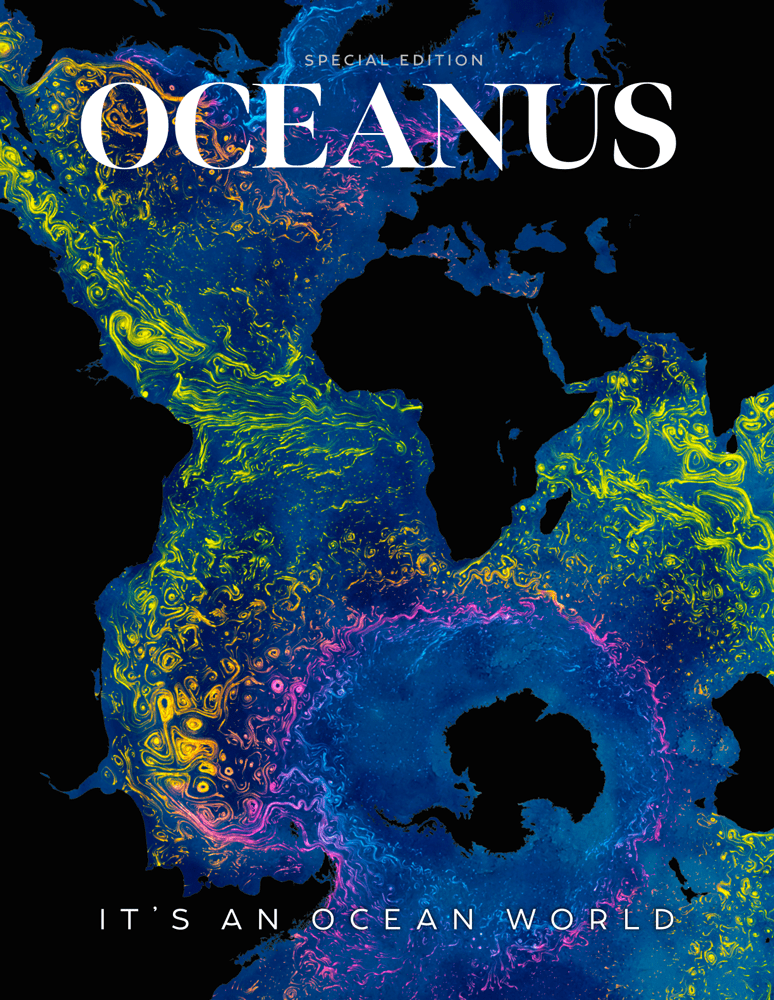

Farewell to the Knorr

Research ship and crew made oceanographic history

Oceanographer Bob Pickart will never forget his first cruise aboard Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (WHOI) research vessel Knorr. It was February 1997, and the ship was headed to the fierce Labrador Sea in the dead of winter.

Sailing into the teeth of wintry conditions was the whole point of the 47-day research cruise. Pickart and colleagues wanted to make unprecedented firsthand observations and measurements to learn how frigid air, high winds, rough seas, and sea ice affected the ocean in the region.

As the expedition’s chief scientist, Pickart was nervous. He knew Knorr’s reputation for performing well in winds and waves, but he had never been aboard a ship that had worked so close to sea ice before.

“There was a lot of uncertainty about how successful we’d be taking this ship into high latitudes during winter,” Pickart said. “Knorr is not an icebreaker.”

Pickart assumed it would be too difficult to work on many days and had factored in a lot of lost research time. But Knorr‘s crew came prepared for the ice. Throughout the trip, everyone, from the captain to members of the science party, worked to break up as much as 20 tons of ice that dangerously blanketed the ship to keep the decks and hull clear and the ship stable.

“Before long, it was like, ‘We’re used to this,’ ” Pickart said. “It didn’t faze them. They were good at it. They were able to adapt.”

Pickart lost only about 36 hours of work time to bad weather, a fact he still marvels at today.

“We got more than twice the amount of work done that we expected,” he said. “It was not only the ship that was capable, it was the crew that was so experienced. They just took on the challenge. They were all about seeing what the scientists wanted and making it happen.”

Pickart’s experience aboard Knorr is not unusual. Over the past 44 years, Knorr has conducted research from the Arctic Circle to the Southern Ocean and many places in between. Knorr has also taken part in some of the 20th century’s greatest ocean discoveries, from locating the wreck of R.M.S. Titanic to finding completely unknown and unexpected life forms on the seafloor.

When Knorr retires at the end of 2014, it will have traveled more than 1.35 million miles—a distance equivalent to more than two round trips to the moon. Its experienced and dedicated crew earned a reputation for safely and effectively conducting research in difficult conditions. Together, Knorr and its crew expanded the limits of our understanding of our planet.

Auspicious beginnings

When Knorr’s keel was laid in Bay City Michigan in 1967, Americans’ enthusiasm for science was at an all-time high. The nation’s space program had ramped up, and NASA engineers were building Apollo space capsules and putting men on the moon. Meanwhile, ocean scientists and engineers at WHOI had just finished designing and building Alvin, the submersible that brings humans to the seafloor. The 1960s and ’70s also brought an influx of funds to build 20 new research vessels in that time.

World War II had changed the way the world looked at the ocean; it was no longer the dark, cold, barren place researchers had imagined. Post-war U.S. leaders had come to view the ocean as a vast resource of economic, political, and naval importance. If the United States was going to remain the world’s superpower, it needed to maintain command of the ocean.

Knorr was the 15th in this series of ships designed and owned by the Navy and represented the best in technology of that time. At 244 feet, the ship was bigger than its predecessors, with an innovative arrangement that allowed scientists more lab and deck space.

Knorr was also the first American research ship to feature an unusual propulsion system used on European tractor tugs: two German-made Voith-Schneider cycloidal propellers. The propeller blades hung down from circular disks placed near the bow and stern on the bottom of the ship. As the disks whirled around, the blades rotated slightly to direct the thrust. Crew members on the bridge could adjust the angles of the thrust instantly to make the ship much more maneuverable.

“It made the ship so nimble,” said Dick Pittenger, former vice president for marine operations at WHOI. “There’s an old story that when Knorr first came into port, it did a 360-degree turn, then came alongside the dock, just to show how maneuverable this ship was.”

Heralding a new era of exploration

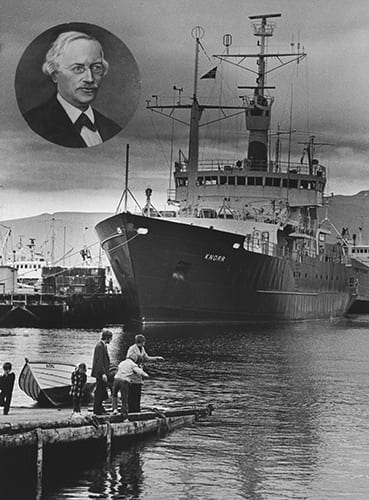

Knorr arrived with that flourish in Woods Hole in April 1970, in time to mark the Institution’s 40th birthday. Some at the Institution had wanted to name the new vessel Oceanus, in honor of the Greek god of the seas. Instead, the Navy chose to commemorate Ernest Knorr, the cartographer who from 1860 to 1885 led the Navy’s first systematic effort to chart and survey the ocean. Nearly 100 years later, the ship served as the backdrop for a new generation of oceanographers, as the first class of the new MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography graduated that June on the WHOI dock.

Knorr also arrived on the brink of the International Decade of Ocean Exploration (IDOE). Led by the United States and supported by the United Nations, IDOE was an ambitious international effort to systematically study the ocean.

Knorr’s first major voyage as part of this effort began in 1972, when the ship left on the first leg of a 30,000-mile expedition for the Geochemical Ocean Sections (GEOSECS) program. The goal was to collect seawater samples throughout the world and analyze their chemical properties to reveal the ocean’s deep circulation.

The ship sailed to the Arctic Circle where scientists tracked a current that originated north of Iceland. The ship then followed the current south, retracing the path Sir Francis Drake had once taken and rounding Cape Horn.

Shaping a ship-shape crew

When the crew wasn’t dealing with the ice and wind of the Southern Ocean, they were feeling the effects of another frigid condition: the Cold War. It was not uncommon for crew and scientists to see Soviet ships lurking in the distance, following Knorr’s movements in those years, said then-Mate A.D. Colburn.

“I remember cruises off Norfolk, Virginia, in the fog with the Soviet ‘fishing vessels’ bristling with antennas coming tight down our port side,” he said. “[There was] a lot of tension, a lot of desire to support research at that time.”

Knorr‘s Captain Emerson Hiller was not about to be intimidated by the Soviets, though. One time, while departing from St. Georges, Bermuda on a cruise, Hiller decided to give a nearby Soviet cruise ship a demonstration of American prowess.

“Captain Hiller came up to the bridge, and he kind of winked at me,” Colburn said. “The lines came in and he took Knorr sideways off the pier. He spun it our own length and went smartly out into the channel. It was just a show of capability and panache.”

Hiller, who had captained two other vessels since joining WHOI in 1959, took over Knorr in 1970 until he retired in 1983. Colburn credits Hiller’s passion for serving science with creating a culture of dedication among Knorr’s crew. In the early years, crew members who worked the deck and those who worked in the engine rooms tended not to mingle, and both kept apart from scientists who came aboard, he said. Hiller broke through those barriers.

“He made it known that we were going to do a good job in support of science,” Colburn said. “We were going to use this wonderful tool, Knorr, to the best of our abilities and the best of its capabilities. That thread continues in Knorr’s crew today.”

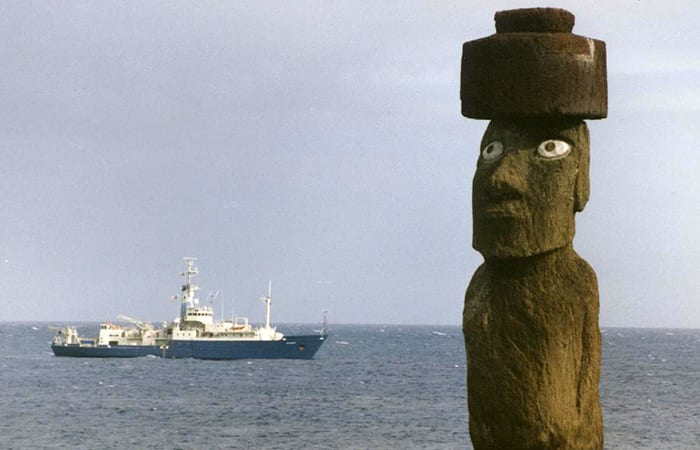

A FAMOUS expedition

Soon after its epic IDOE cruise, Knorr participated in another groundbreaking international collaboration, the French-American Mid-Ocean Undersea Study (Project FAMOUS) in 1973. The ship took scientists to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, part of the continuous undersea mountain chain that encircles the entire planet. Scientists used submersibles, including Alvin, for the first close-up investigation of mid-ocean ridge. They discovered a gnarly, volcanic terrain and cracks in the seafloor big enough to swallow their submersibles.

“I recall the hushed amazement aboard the research vessel Knorr when we first saw high-resolution, deep-tow depth profiles slowly burned onto the paper of our precision depth recorders,” geophysicist Ken Macdonald recalled later in an article in Oceanus magazine.

“The ocean floor is disturbingly different from what we had imagined,” said another scientist aboard, Tjeerd van Andel. The seascape the FAMOUS expedition unveiled provided visual confirmation of what were then nascent theories of plate tectonics and seafloor spreading.

An astounding discovery

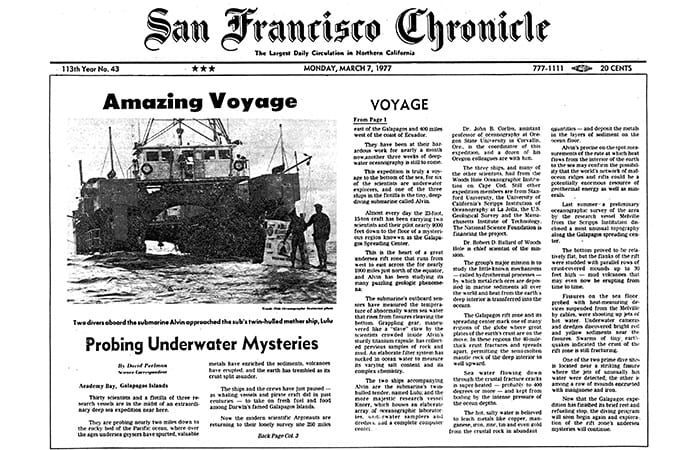

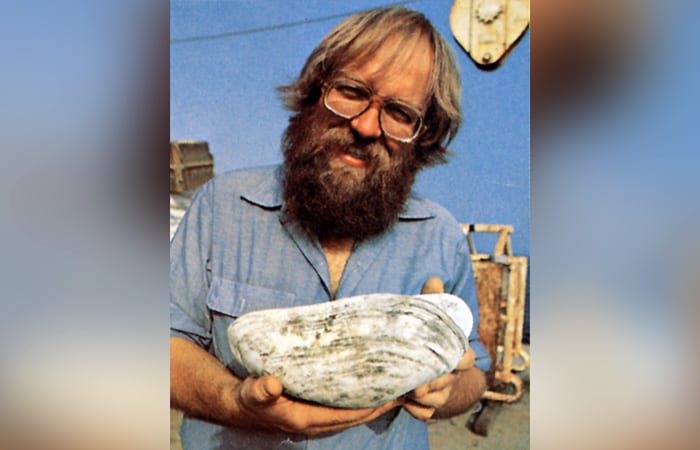

Then, in 1977, Knorr set out on another geology mission to explore a volcanic seafloor spreading center along the Galápagos Rift, some 400 miles off the west coast of South America. Scientists found hydrothermal vents—geysers of hot, chemical-laden fluids gushing out of the seafloor. These were predicted, but what the scientists found around the vents came as a complete surprise.

Perched on the edges of the vents were lush communities of life—crabs, mussels, clams, and six-foot-tall blood-red tubeworms—thriving in a dark, cold world under bone-crushing pressure thousands of feet below the surface. The discovery was pure serendipity. The geological mission had suddenly turned into a biological expedition.

“When they started running across animals, they weren’t the least bit prepared to deal with them,” said WHOI acoustic navigator Steve Gegg. To preserve the specimens they collected (in days before liquor was prohibited on research vessels), “they had to put them in people’s vodka.”

It was one of the most profound scientific discoveries of the 20th century. The longstanding theory that large and abundant life required the sun to survive had been turned upside down.

It was like discovering life on another planet, said Gegg. “It was crazy. If you had to come up with a movie about aliens, you’d be designing these tubeworms,” he said. “Listening to the scientists, I realized the importance of it. They wondered, where did [the organisms] get their food? How did they survive in such dark, cold conditions?”

Scientists would subsequently learn that the organisms were harnessing energy from chemicals spewing from the vents, using a process known as chemosynthesis. Scientists still study the vents and the organisms around them today, searching for more clues to illuminate how life on Earth evolved and how life might exist elsewhere in the solar system.

Lost and found

Knorr was also the ship on the scene for yet another major oceanographic discovery in 1985, when R.M.S. Titanic was found. A team of American and French scientists, led by then-WHOI oceanographer Bob Ballard, located the storied shipwreckwhile on a classified Navy expedition to explore a sunken nuclear submarine in the North Atlantic.

The Navy had agreed to search for Titanic after work was completed on the submarine. Scientists instructed Knorr’s crew to make long back-and-forth transects across an area where they speculated Titanic might be found, and to stay close to that cruise track. They towed Argo, a sled equipped with cameras, on a long wire just above the seafloor. They all knew the chances of finding the wreck were slim; the planned transects were, at best, educated guesses.

“We spent weeks, it seemed, traversing over mud and getting nowhere,” Gegg recalled. “Then we came across this one [potential] target, and it really stood out. There was quite the discussion about whether we should go after it. I voted to go for it. But, Ballard said no, and we kept going.”

It’s a good thing they did. With just a few days of the expedition left, Argo glided over a boiler the size of a two-car garage and took a photo. They had discovered Titanic’s debris field, two and a half miles below the surface, nearly 400 miles south of Newfoundland.

Everyone aboard the ship erupted into a frenzy of celebration. Tito Collasius, then a dishwasher, remembered the excitement. The 20-year-old was on his first cruise for WHOI after leaving the Navy, and he was more than a little awed by the people who had done what had seemed so impossible.

“The atmosphere was absolutely crazy. The ships were wet back then,” he said, meaning liquor was permitted. “So there was a lot of celebrating going on.”

Nearly 30 years later, Collasius is the expedition leader for the remotely operated underwater vehicle Jason. He credits his first trip on Knorr with inspiring him to make a career working himself up the ranks at WHOI.

“There was an obvious sense that I had been a part of history,” he said. “It’s even more amazing now that I’ve been exploring.”

Carefully exploring ‘an old friend’

Word spread home to the United States and France, and soon Knorr was besieged with calls from around the world.

“It’s like it’s an old friend. It’s so nice to see it and know exactly where we are,” Ballard told reporters in on a call from the ship that aired nationwide on American TV networks. “It’s like going back in time. It’s a memorial for a lot of people that died.”

The complicated operation needed the absolute cooperation and expertise of the ship’s crew to ensure no gear was lost and the shipwreck wasn’t damaged any further. Deck officers often steered the ship remotely from the science lab.

“They had to believe in driving by the numbers,” Gegg said. “If you were going to do it with any crew, I’d do it with them.”

Each time they deployed the sled, scientists saw new features of the wreck. They collected photos and video of baggage, cases of wine, and unbroken china strewn across the seafloor. They surveyed the bow and bridge and took pictures of a portion of hull they thought might have sustained the damage from hitting the iceberg that night in April 1912.

A triumphant welcome

When Knorr returned to Woods Hole in September 1985, WHOI’s small dock was crammed with people who turned out to greet the science team and learn more about Titanic. Nearby Water Street was filled with TV crews.

“Knorr steamed into the kind of welcome that might have greeted the Titanic had the famed luxury liner completed its maiden transatlantic voyage 73 years ago,” a Los Angeles Times journalist wrote at the time. “Ship horns blared, a cannon roared, hundreds cheered from piers and rooftops, festive balloons spiraled high, champagne corks popped, banners fluttered, and dozens of reporters clamored.”

Gegg had been flown home mid-cruise by helicopter, and then Learjet, carrying footage of the wreck for TV stations. When Knorr returned, he went out on a small boat to ride in with the team, armed with a special gift to honor their discovery.

“I took them a pizza,” he remembered with a smirk. “I wouldn’t have missed that for the world. It was unbelievable [coming in]. You could not see the WHOI dock.”

Knorr‘s discovery of Titanic publicized the name of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution worldwide.

Mid-life makeover

In 1989, Knorr was reaching a bit of a mid-life crisis. While the ship’s cycloidal propellers made it easy to maneuver and keeping the ship “on station,” or maintaining one position at sea, they also made the ship slow.

“[They were] the great eggbeaters hanging down beneath the ship,” Colburn said. “The joke was that Knorr could go in any direction except straight ahead.”

The cycloidal props and shaft vibrated so much, they broke massive metal gear teeth and broadcast noise into the water, said Dutch Wegman, who served on Knorr for five years. The system experienced frequent mechanical failures, and Knorr needed to go to a shipyard nearly every year to replace components.

It was decided that Knorr would not only get a new propulsion system, it would also be “jumboized” by cutting the ship in half and adding 34 feet to its middle. Knorr went to McDermott Shipyard in Louisiana, a yard known for building rigs for the offshore oil industry.

“It was a big, big shipyard,” retired WHOI naval architect Jonathan Leiby recalled. “But by the time we got there—we didn’t realize it—but there had been such a downturn in activity along the Gulf Coast that lots of people had been laid off, and some of the best ones were gone.”

The yard struggled to properly refit Knorr and its sister ship, Melville. Problems and delays plagued the $32-million project. First, asbestos was in nearly every wall and ceiling that workers opened. Then, the yard had issues installing new piping.

“You had people doing construction things that they had to do two and three times because they couldn’t get it right,” Leiby said. “It was a disaster in all capitals.”

On a dreary October day in 1991, Knorr finally returned to Woods Hole, three years after it had left for the shipyard. The ship was now 279 feet long and had a new state-of-the-art propulsion system to allow the ship to travel faster while remaining maneuverable. It had more deck and berthing space to accommodate more scientists for longer expeditions. Knorr was ready again to conduct research, but the crew had to work through lingering problems.

On the voyage back to Woods Hole, Engineer Steve Walsh, who first sailed on Knorr in the engine department in 1985, said he barely had time to go to the bathroom. “It was just alarms constantly, and everything was new. It took years to get some systems working smoothly.”

Back on the job

Despite its initial problems, the “new” Knorr was a vastly improved ship. In 1992 it began work as part of yet another multinational collaboration, the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE). This time, scientists were interested in learning more about the role of the ocean’s circulation in regulating Earth’s climate. The goal was to take samples every 100 miles to build the most comprehensive dataset ever collected from the world’s ocean.

Over the next decade, Knorr once again left for long voyages, often working in rough weather. The ship again circumnavigated the globe, conducting research from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean, through the Atlantic and into the Pacific.

The ship and crew became intimately familiar with the challenging conditions in the lower latitudes, and after a winter trip off the coast of South America, they would learn just how challenging conditions could be.

“We had done 40 days or so at sea, and it was grueling, people were just worn down,” said Colburn, who took over the helm as captain in 1996. “We pulled into port, and I said to the one of the locals, ‘Hey, we’re going to be back here to do this again in the summer; what’s it like?’ ”

“The guy looked at me and pointed to a little tree that was blown over at a 45-degree angle and said, ‘That’s because of the summer,’ ” Colburn said. “Those are some of the conditions the Knorr successfully navigated.”

Surmounting gender barriers

While the ship was helping scientists push the limits of ocean science, the crew was quietly pushing the limits of who could go to sea, starting with Project FAMOUS in 1973.

“Women at sea were by no means commonplace in the early 1970s,” wrote Kathryn Sullivan in an article in Oceanus magazine. “Knorr’s scientific rosters show that 38 people sailed as members of the scientific parties during the various FAMOUS voyages. The eight women among them probably represent the first significant female participation at sea in a large oceanographic program.”

Sullivan, a first-year graduate student aboard Knorr during project FAMOUS, was named administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2014.

Women, who for decades been excluded from jobs as professional sailors, began to break down those barriers in the 1970s and 80s.

The first woman to sail in the engine department on a WHOI ship, Kathleen Hoad, came aboard Knorr in 1981. More women began to sail on WHOI ships in 1990s, including cook Mirth Miller, who started on other WHOI ships before moving over to Knorr, where she became steward. She stayed because the crew accepted her and the work was fun and interesting, she said.

“To me, the [scientists] that come on are so into their work that you’re sitting having a drink with them, and they’re talking about the vectors in your drink—how the alcohol moves through the ice water,” she said, laughing. “You learn a lot, and you get interested. Their enthusiasm definitely pulled you in.”

Glass ceilings at sea

Sailing as a woman wasn’t without its quirks. Miller was not thrilled when, during a drill to prevent pirate attacks, all women aboard were instructed to hide rather than help.

“If the pirates came on, I was supposed to hide [the women] under the floor boards in the engine room, which was just kind of funny,” she said. “It seemed so weird to think that these ships, if they’re dealing with something like that, would have fire hoses while the pirates had Uzis.”

Her crewmate, then-Second Mate Dee Emrich, was downright mad.

“Mirth and I kind of egged each other on,” she said. “I remember hissing across the table to the captain one day, ‘What makes you think I can protect you any less than you can protect me?’ ”

Knorr can also boast the first woman bosun, or deck boss, in the WHOI fleet. Lorna Allison was promoted to the position in the mid-2000s and sailed when the regular bosun was on vacation. She broke one of the last barriers to women in the WHOI fleet, said Knorr Captain Kent Sheasley.

“Part of my job is putting people in the right spots, and I remember calling her up one time and saying, ‘I think you get it,’ ” Sheasley said. “She was competent. She had high standards.”

The nation of Knorrons

Knorr has always attracted the kind of people who would drop everything for a crewmate in trouble, Sheasley said. “It’s a common mindset,” he said. “You want people to be proud to simply say, ‘I’m one of them, I’m a Knorron.’ ”

The fact that so many of the crew have been at WHOI for so long also helps when times get tough. Wegman, who sailed on Knorr for the first time in 1976, is now WHOI port engineer overseeing ship maintenance. His experience as an engineer on Knorr is still invaluable, Emrich said.

“Nobody knows the Knorr like Dutch does,” Emrich said. “This ship will always be his first love. Every single time he’s on Knorr, I always learn something from him.”

WHOI physical oceanographer Bob Weller agreed. “Woods Hole has always had a hallmark of keeping the crews with the ships, so it always seemed like when you came aboard, you sort of knew exactly what you got, and they participated intimately with the work,” he said.

University of Washington physical oceanographer Craig Lee said Knorr’s crew was a major reason why he has sailed more than a dozen times aboard the ship on science expeditions over the last 14 years.

“You don’t get a team like that every day,” he said. “Knorr is just truly exceptional as far as their enthusiasm for the mission. They behave as a small family and look out for each other.”

An extraordinary effort to save a life

The heart and soul of Knorr’s crew is perhaps most evident in the story of Joe Mayes. Mayes was a well-liked oiler who collapsed aboard the ship on New Year’s Day, 2001. The 46-year-old had begun suffering from headaches that became so severe he went into respiratory arrest.

Knorr was investigating a previously unexplored section of the global mid-ocean ridge in the Southern Ocean, 1,200 miles from the nearest shore.

“We are 9-1-1,” Emrich said. “Fortunately because of the remoteness of it, we had a registered nurse with emergency room experience for that cruise.”

The entire ship worked in 15-minute shifts, hand-pumping an airbag every five seconds to keep Mayes breathing. When the limited supply of oxygen ran out, the crew continued pumping, using regular air. But the dry Antarctic air was causing problems in Mayes’ lungs. Chief Engineer Steve Walsh rushed to concoct a system that would humidify the air and make it easier for Mayes to breathe.

“I came up with a little tray filled with water,” Walsh said. “We put a clean mop head on it and filled it with water and a fan on the wall behind the bed. A thermostat behind the bed registered 100 percent humidity.”

The crew kept Mayes alive until they were close enough to shore for a helicopter to reach them. Though he was still alive when he was brought to a hospital in South Africa, Mayes died shortly after.

Over the four-day transit to helicopter range, the crew had pumped nearly 80,000 breaths into Mayes. Knorr’s crew was later presented with the institution’s Penzance Award for their exceptional heroism and dedication.

The Long Core

Knorr traveled back to the shipyard in 2005 for one last major refit to handle a new one-of-a-kind tool. Called the Long Core, it could extract undisturbed plugs of seafloor sediment up to 150 feet long. It was twice as long as existing coring equipment and weighed nearly five times as much. The ship emerged 50 tons heavier, with new equipment and massive modifications to accommodate the huge core weight dangling into the depths from the ship.

WHOI engineer Jim Broda designed the Long Core and was happy to see Knorr outfitted to carry it. Broda was an honorary Knorron, having sailed on Knorr more than 30 times over his career, so he knew the ship’s crew would be able to help him deploy the system.

Broda was especially happy his tool was on Knorr the night a mechanical component failed, leaving more than 14,000 feet of rope and the coring tube floating in the Pacific Ocean.

“I thought we’d have to abandon the instrument, put a buoy on [the rope] and come back to recover it later, after a failed winch was repaired,” Broda said. “But the captain said, ‘We’ll get this.’ He was determined that we could recover the core. It was incredible.”

The group brainstormed ways to get the system back; they would need to harness thousands of pounds of tension to wind the rope onto the ship and recover the coring device. Nine and a half hours later, everyone, led by the captain, had taken part in bringing the rope back on deck and coiling it securely on the bow. The action saved Broda’s team hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost equipment and enabled research operations to continue.

WHOI’s sea-going tradition goes on

Knorr conducted its last Long Core mission in November 2014. After hundreds of science expeditions, and port stops in more than 40 countries, the ship will return to the Woods Hole dock Dec. 3, to a crowd waiting to greet it.

The ship’s fate is still unknown. Though the Navy has retired it from service in the United States, Knorr has good years left. The ship will be replaced in 2015 with a new ship named after one of Knorr‘s contemporary explorers, Neil Armstrong, who made a giant leap for mankind when he stepped on the moon just one year before Knorr’s first voyage.

“We’re going to miss that boat, absolutely,” Emrich said. “It’s hard to let go, even when you want to go screaming down the gangway.”

Knorr’s crew will transfer their experience and knowledge to Armstrong, getting it ready to serve science and continue in the sea-going tradition long-upheld by Knorr and the other ships in the WHOI fleet.

“Knorr is going out as the can-do, go-to boat,” Sheasley said. “We go the extra mile, plus one.”

Slideshow

Slideshow

- The research vessel Knorr arrived in Woods Hole in April 1970 just in time to serve as a backdrop for the first graduating class of the MIT-WHOI graduate program in oceanography. (WHOI Archives)

- Knorr was owned by the Navy and operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution from 1970 to 2014. It was named after Ernest Knorr, the cartographer who led the Navy’s first systematic effort to chart and survey the ocean, from 1860 to 1885. (WHOI Archives)

- Knorr took scientists to get their first surprising views of the seafloor on the mid-ocean ridge in the historic French-American Mid-Ocean Undersea Study (Project FAMOUS) in 1973. The research cruise was historic in another way: Eight women aboard represented the first significant female participation at sea in a large oceanographic program. Over the years, Knorr also broke barriers to welcome women aboard WHOI ships as crew members. (WHOI Archives)

- In 1977, scientists aboard Knorr made one of the most profound discoveries of the 20th century. They unexpectedly found lush communities of animals and microbes thriving without sunlight around hydrothermal vents on the seafloor in the Galápagos Rift. (San Francisco Chronicle)

- Among the exotic organisms discovered around hydrothermal vents were blood-red tubeworms encased in 6-foot-tall white stalks. (WHOI Archives)

- Jack Corliss, a geologist at the University of Oregon in 1977, holds a giant clam sampled from hydrothermal vents sites. The expedition was searching for hydrothermal vents and found them, but also unexpectedly found chemosynthetic life around the vents. (Emory Kristof)

- Veteran WHOI seaman Emerson Hiller was Knorr's captain from 1970 until he retired in 1983. He is credited with setting the standard for the crew's hard work and dedication to accomplishing scientific missions. (WHOI Archives)

- Knorr’s crew affectionately called themselves Knorrons. Many stayed aboard for decades, becoming a tight-knit group. They worked closely with scientists, and had a knack for overcoming challenges. On a Labrador Sea cruise in the winter of 1997, all hands had to break dangerous ice buildup from the bow, including then-Captain A.D. Colburn, swinging a mallet. (George Tupper, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

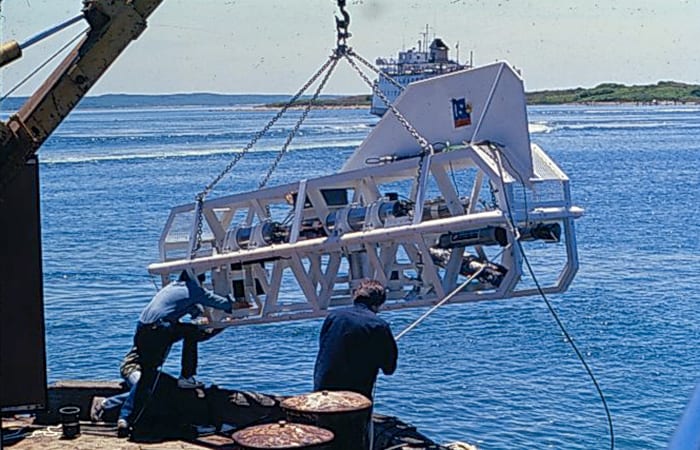

- In 1985, Knorr was the ship on the scene when the wreck of Titanic was discovered. To search for the wreck, the ship used a long wire to tow Argo, a sled equipped with cameras, just above the seafloor. (WHOI Archives)

- After searching for three weeks, and with just a few days of the expedition left, Argo glided over a boiler the size of a two-car garage and took a photo. They had discovered Titanic’s debris field, two and a half miles below the surface, nearly 400 miles south of Newfoundland. (WHOI Archives)

- The pier at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution was crammed with people and media eager to welcome the ship, scientists, and crew after they had discovered the wreck of Titanic in 1985. (WHOI Archives)

- Knorr was the first U.S. research ship to feature an unusual propulsion system: Voith-Schneider cycloidal propellers. The propeller blades hung down from circular disks placed near the bow and stern on the bottom of the ship. As the disks whirled around, the blades rotated slightly to direct the thrust. Crew members on the bridge could adjust the angles of the thrust instantly to make the ship much more maneuverable. (WHOI Archives)

- In 1989, Knorr went into the shipyard to get a midlife refit. The ship was “jumboized” by cutting it in half and adding 34 linear feet to its middle. (WHOI Archives)

- The heart and soul of Knorr’s crew is perhaps most evident in the story of crew member Joe Mayes, an oiler who collapsed aboard ship in the Southern Ocean, far from the nearest port. The entire crew worked in shifts, using an airbag to manually keep Mayes breathing for four days until he was evacuated by helicopter. Sadly, he died shortly after in a hospital. (WHOI Archives)

- In 2006, Knorr went back to the shipyard, this time to be refitted for a new tool called the Long Core. The massive instrument was nearly twice as long, and four times as heavy, as existing coring systems. It could collect sediment cores up to 150 feet into the ocean bottom. (Jim Broda, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Over its 44-year career, Knorr sailed 1,358,000 miles on more than 300 scientific voyages. The highest northern latitude it reached was 80°N; the highest southern latitude it reached was 68°S. (WHOI Archives)

- Knorr sailed throughout the world's ocean, stopping along the way in 46 countries. (P.E. Robbins, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Video

Related Articles

- A new underwater robot could help preserve New England’s historic shipwrecks

- Five marine animals that call shipwrecks home

- Can environmental DNA help us find lost US service members?

- Re-envisioning Underwater Imaging

- Inside the Sunken USS Arizona

- Ancient Skeleton Discovered

- Why Did the El Faro Sink?

- A Luxury-Laden Shipwreck from 65 B.C.

- High-tech Dives on an Ancient Wreck

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Losing a Mate, Finding Themselves An article on Joe Mayes and the Knorr crew from Currents magazine

- R/V Knorr

- The 25th Anniversary of the Discovery of Hydrothermal Vents

- Adventure in the Labrador Sea Oceanus magazine

- WHOI Ships