- WHOI postdoctoral scholar Kirstin Meyer, visitor Megan Bouch, and guest student Nicole Pittoors (left to right) collect plastic monitoring panels that hung in the water off the WHOI pier for two weeks at a time through the spring and summer. She hung another set of panels off the dock in nearby Eel Pond. Her goal? To compare which animals would settle and grow over time in the two locations. (Véronique LaCapra, WHOI)

- Each week, Meyer found new animals growing on her panels, including these brownish bryozoans and orange tunicates, along with barnacles, sponges and other invertebrates that make up a biofouling community. Meyer saw the community shift as water temperature rose from spring into summer and as later arrivals competed for space. (Véronique LaCapra, WHOI)

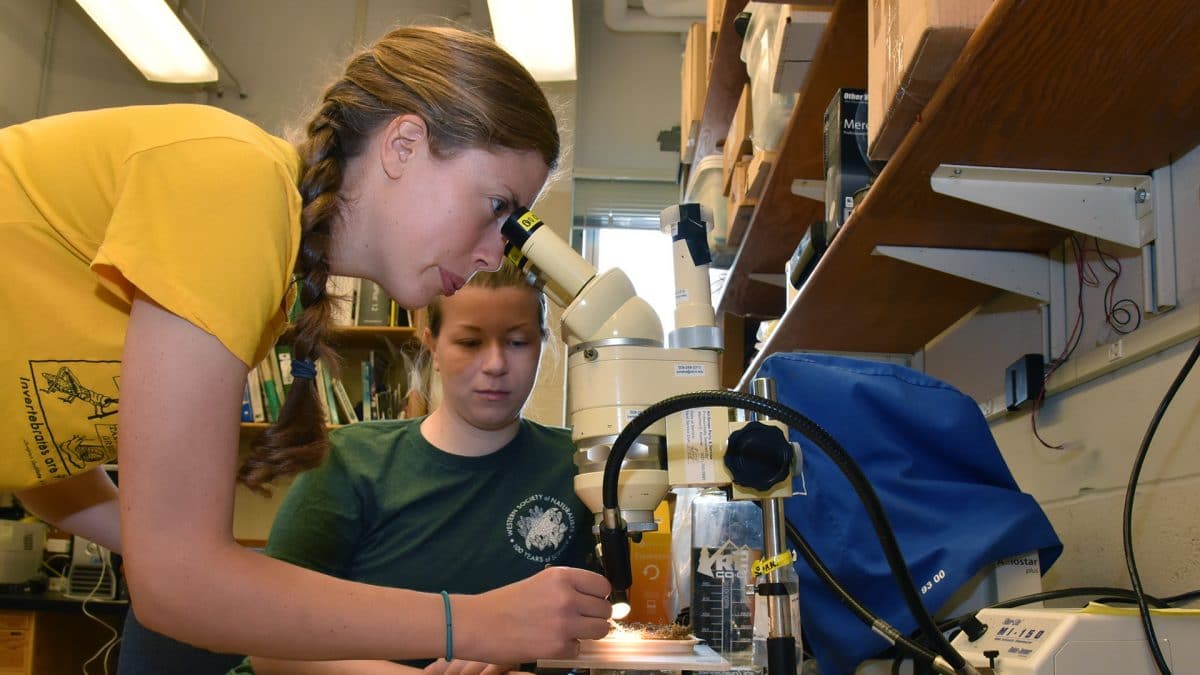

- Meyer and Pittoors painstakingly examined each panel under a microscope in their lab to tally what had grown there. Sometimes, says Meyer, the animals coated the panels so densely they could not count individuals. In those instances, they estimated abundances by measuring the area covered by each species. (Véronique LaCapra, WHOI)

- In spite of their unflattering moniker, “biofouling” invertebrates can be surprisingly beautiful. The “petals” of these delicate golden “flowers” are actually individual animals: clones of the colonial star tunicate Botryllus schlosseri, growing on top of another colony of sea squirts, the bright orange Botrylloides violaceus. (Kirstin Meyer, WHOI)

Who Grows There?

Scientists take a closer look at biofouling marine life

If you’ve spent time by the ocean, you’ve probably seen the masses of barnacles, sponges, and other invertebrates that grow in abundance on submerged rocks, boats, docks, aquatic plants, and even the shells of snails and other marine life. Kirstin Meyer investigates how those so-called biofouling communities emerge and evolve.

In the spring and summer of 2017, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution postdoctoral scholar hung plastic panels off the WHOI pier and in nearby Eel Pond in Woods Hole, Mass., to monitor what would grow on them.

“I wanted to know not just what the communities look like after an indeterminate amount of time, but how they developed from the very beginning,” Meyer said.

She’s particularly interested in the “mechanisms of succession” that drive the composition and ecology of coastal biofouling communities.

“Succession is how a community of animals develops over time—what things settle when,” Meyer said. “Mechanisms refer to the particular ways that those species are interacting.”

Her preliminary results suggest that water temperature and competition among species primarily determine who survives and who doesn’t and how the assortment of species changes over the course of the seasons.

Meyer says her work could help prevent the spread of invasive species, which often dominate biofouling communities.

“If we understand how the organisms interact with each other and why they settle in the order that they do,” Meyer said, “then we can start to understand how these invasive species become established.”

While she was doing her field work, Meyer also had to contend with another kind of “invasive” species—summer tourists.

“I’ve had a couple of people stop me and ask what I’m carrying,” Meyer said. “I have these dish racks that I put my fouling panels in, and people give me really funny looks.”