Two Ships Passing Passengers in the Night

WHOI research vessels Knorr and Tioga rendezvous at sea to evacuate injured mate

Into the frigid darkness, following two days of stormy weather, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s coastal research vessel Tioga left port shortly after 10 p.m. on March 6, with sea spray freezing immediately on its railings and windows. It was headed for a rendezvous with its big sister ship, Knorr, which had been thundering home since the previous morning, against 35- to 40-knot storm winds and 20- to 25-foot seas that relentlessly pounded its bow.

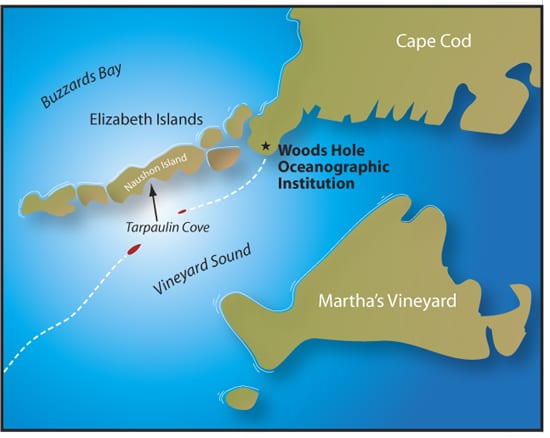

Knorr had to evacuate its third mate, Derek Bergeron, who had injured his hand during a rescue boat exercise on a research cruise 300 miles southeast of Cape Cod. Off Naushon Island in Vineyard Sound, the 60-foot, aluminum-hulled Tioga pulled alongside the 279-foot, steel-hulled Knorr to attempt an at-sea transfer. The winds had eased to about 16 to 20 knots, but the seas were hardly calm. The air temperature was 4°F.

Two days before, Knorr’s captain, Kent Sheasley, had notified Al Suchy, WHOI’s ship operations manager, about Bergeron’s injury.

“Immediately following the injury,” Sheasley said, “we consulted with our ‘on-call’ MedAire Medical Advisory Systems,” which links ships with shore-based physicians via satellite telephone. “It was decided that if the pain and swelling did not ease significantly by morning, it was highly likely that (Bergeron) had a broken bone in his hand. ”

Suchy contacted Mike Brennan, WHOI marine personnel coordinator. Brennan began making telephone calls and sending e-mails from home on Sunday to find an available mate to relieve Bergeron on short notice, so that the science cruise could continue.

On Monday morning, the swelling in Bergeron’s hand had increased. “It was obvious we had to get him in,” Sheasley said.

Winds, waves, and waiting

Knorr headed home, trying to locate a vessel that would rendezvous with it off shore, Sheasley said. Because Knorr was coming from Bermuda, a foreign port, docking at WHOI would have required hours of official protocols, which threatened to compromise a multiyear study of wintertime Gulf Stream air-sea interactions that influence the climate. (See “The Hunt for 18° Water.”)

Knorr turned northwest, right into the teeth of a fierce storm. Through the late day Monday and overnight, Knorr sailed directly into 35- to 40-knot winds and 20- to 25-foot seas. The ship, which normally makes 11.5 knots, averaged only 6.5 knots. It had accumulated about three inches of ice from freezing spray.

Meanwhile, Brennan had located a relief mate: Allison Tunick, who had worked on Knorr in the summer of 2006. But she was in California, and Brennan arranged for her to take a red-eye flight Monday. She arrived Tuesday morning, the time when Sheasley had originally estimated Knorr would arrive in Vineyard Sound. But the ship was still en route and “still trying to find a vessel willing to come out and meet us,” Sheasley said. “The weather was keeping everyone in.”

Ken Houtler, Tioga’s captain, had been monitoring the situation since Sunday. As Knorr neared Woods Hole, he volunteered to meet it. So did Ian Hanley, Tioga’s mate, Liz Caporelli, WHOI marine operations coordinator, and John Dyke, WHOI marine resource coordinator, who waited into the evening for Knorr.

“Larry Costello from the rigging shop volunteered and Geoff Ekblaw from the welding shop,” Houtler said. “We could have gotten 10 other people, if we had asked and if we had needed them. We’re pretty used to working in nasty conditions, and we take care of our own.”

A good lee

Knorr finally arrived at 9:30 p.m., and Tioga headed out with the four-person crew, Tunick, and Apurva Dave, a graduate student from Duke University who had been scheduled to board Knorr in Bermuda a few days before. The same storm that buffeted Knorr had forced a cancellation of his flight from Atlanta to Bermuda, so he missed the ship. Taking advantage of this unplanned personnel transfer, Dave flew instead to Boston.

Everyone was dressed in exposure suits against the biting cold. “The decks were icy,” Caporelli said. “Ian did his best to shovel them clear.”

“Normally,” Sheasley said, “transfers of this kind would be done using a smaller work boat, as any contact, even slight bumping, of two large vessels can do some serious damage, usually to the smaller vessel. But the process of launching a work boat would have been dangerous as well, given the weather conditions, especially the cold. Captain Houtler decided he would maneuver the Tioga alongside the Knorr and conduct the transfer directly.”

The two captains decided to rendezvous in Tarpaulin Cove on the east coast of Naushon Island, about half a nautical mile from the beach. “It’s fairly deep in there,” Houtler said, “and Knorr could get up inside, which provided a good lee”—protection from the waves and winds.

“There was approximately 2.5 knots of current running through Vineyard Sound at that point,” Sheasley said, “so the Knorr had to hold against that current and the wind, and also block those effects as much as possible for the Tioga. Unfortunately, the Tioga still had less than ideal conditions to bring a vessel her size alongside the Knorr.”

Hull to hull

“The ships were moving; there’s no way to stop that,” Houtler said. He decided that he did not want any lines passed between ships. “ I didn’t want to be hard and fast. I wanted to be free to maneuver as necessary” and continually adjust to the dynamic conditions.

“It’s not like pulling a car alongside another,” Caporelli said. “Boats can’t put on the brakes. They can only stop a motion with a reverse motion.”

“For eight minutes—a long time when it is happening,” Sheasley said, “[Houtler] held the Tioga within two feet in any direction. The Knorr had to maintain a solid position to not add to the dynamics Captain Houtler had to contend with.”

“Dock to dock, it only took Tioga an hour, but while the boats were together, it was a long time,” Houtler said. “It was tense, a little sweaty.”

Crew members aboard Knorr lowered a ladder three to four feet down to Tioga. “My impression was that the Knorr would be much taller than we were once alongside, but they lined up fairly well,” Houtler said.

Safely ashore

With crew members above and below firmly holding onto the transferees’ arms and shoulders as the vessels bobbed asynchronously in the waves, Bergeron was transferred to Tioga and Tunick and Dave and their luggage went aboard Knorr.

“Apurva had never been to sea before, so I had been talking to him about what it’s like,” Caporelli said. “I told him, ‘This isn’t normally how people get on a ship. Normally they walk up a gangplank.’ ”

“Derek was generally in good spirits,” Houtler said. “But he felt bad about leaving the ship. It’s always tough to get out with only half the job done and see your mates sail off.”

Bergeron was taken straight to a hospital. He subsequently was examined by orthopedic specialists to see if he requires surgery to facilitate healing of his fractured metacarpal bone.

Knorr returned to work. “On the way out,” Sheasley said, “the weather had eased, and what winds and seas we had were behind us, making a much easier ride than on the way in.”

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

- WHOI's 60-foot, aluminum-hulled coastal research vessel Tioga. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Instiution)

- WHOI's 279-foot, steel-hulled research vessel Knorr.

- R/V Knorr battled rough seas to return to Vineyard Sound. Tioga left Woods Hole to meet its big sister ship. (Map by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- To evacuate an injured mate from Knorr, the captains of the two ships decided to rendezvous in Tarpaulin Cove off Naushon Island, which provided some protection against winds and waves. (Map by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Ken Houtler (at the wheel), captain of Tioga, and Ian Hanley, Tioga's mate. (Photo by Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Kent Sheasley, captain of R/V Knorr (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Topics

See Also

- Research Vessel Knorr

- Coastal Research Vessel Tioga

- Research Vessel Knorr from Dive & Discover

- Where is Knorr now?