The Call of the Sea

An ocean engineer-turned-businessman returned to WHOI and the work he loves most

Marshall Swartz’s lab is a Santa’s workshop of engineering gadgetry. Computer keyboards and circuit boards spill from cardboard boxes. Cables, wires, and an assortment of tools hang from wall hooks. Ocean instruments needing repair are stacked in cases near the door. Swartz’s Labrador retriever, Little Bear, naps in the only available floor space—under a table.

To an outsider it might look like a mess. But in each wire, cable, and connector switch, Swartz sees potential for turning ordinary equipment into extraordinary deep-sea research instruments.

For geologists who want to photograph seafloor volcanoes and valleys, Swartz has made cameras capable of holding up against pressure miles under the sea. He’s made lights to illuminate their way in the depths. He has resuscitated chemical-sniffing instruments flooded with salt water and saved balky, multimillion dollar fiber-optic cables from the junk heap.

Most recently, he transformed a decades-old technology—steel-coated cable—into a high-speed data link into the deep, giving thrilled scientists a faster, easier, and cheaper way to get information about the ocean. He relied mostly on off-the-shelf computer hardware and software to develop an Ethernet connection on the cable, an idea once considered a pipe dream.

“I try not to live with the status quo,” Swartz said. “I like to find out what things could be, and not just accept how they are.”

A dog in every port

Swartz, 56, first came to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in 1976 as an engineering major fresh out of Duke University. After a break to earn an MBA and to work for two large manufacturing companies, he returned to WHOI in 1992.

Since then he has become one of the Institution’s more popular go-to guys for repairing broken gear and building new tools.

“He’s a frighteningly capable engineer,” said George Tupper, a retired engineer in the physical oceanography department at WHOI. “He’s a walking encyclopedia willing to work 18 hour days on behalf of science.”

“I like what I do, and I like that what I do is useful to other people,” Swartz explained.

He’s known for his fastidious attention to detail (“He makes sure that the fifth number to the right of the decimal point is accurate,” Tupper said) and for acts of kindness commensurate with his size (he’s 6 feet 3 inches tall and wears size 13 sneakers).

Dogs, especially, are his passion. Rhian Waller, an assistant professor at the University of Hawaii, recalled the walk she took with Swartz last year in Chile before a research cruise to Antarctica.

“Here’s this jolly American, probably twice the height of most Chileans, strolling with pockets of dog treats,” Waller said. “Every street dog from miles around followed him to the dock. I’m sure those pups all missed him when we finally pulled away from Punta Arenas.”

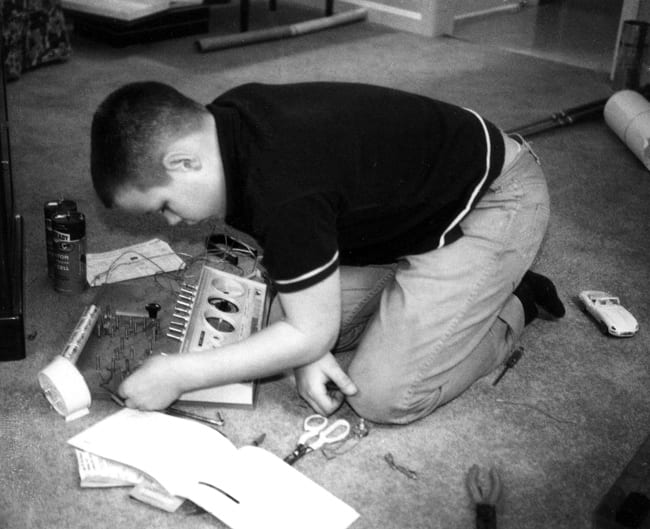

Discovering how things work

Swartz still owns the pink brick house where he grew up in rural Pennsylvania. His father, an attorney, wasn’t mechanically minded, but he appreciated the curiosity of his only child. He plied his son with Tinkertoys, Erector Sets, and Legos and read to him from the family’s home library (Tom Swift, a young inventor, was among Swartz’s favorite literary characters).

Swartz’s dad also encouraged him to explore.

“Where I grew up you could go a half mile through the woods and there was a junkyard with cars from 1920,” Swartz said. “The guy there would let me take them apart and put them together.”

As an adolescent, Swartz spent summers repairing outboard motors at a marina in northern Michigan, where his family vacationed. “I’d hang around taking the jobs the other guys didn’t want, and I usually didn’t get paid,” he said. “My father would say, ‘We came up here so you could work for free?’ But it was what I wanted to do.”

One key to his engineering success, he said, is that “nobody said no. Nobody said, ‘you’re just a kid.’ They said, ‘try whatever you want.’ It’s why I’m not hesitant to modify things to my own liking.”

In high school, a wealthy neighbor paid Swartz $2.50 an hour (“a ton for a teenager in the 1960s,” Swartz said) to work as his mechanic. Swartz’s job was to duplicate tapes that the neighbor, who made his fortune selling cemetery plots along the East Coast, used to train his sales staff. Swartz also helped maintain the neighbor’s fleet of 12 Mercedes-Benz cars, including a 1958 convertible as blue as a robin’s egg.

“He let me drive that car all through high school,” Swartz said. “I realized quickly that I could learn from this self-made man.”

Swartz’s other interest was rock music. His freshman year of high school, he saw his first concert: the Grateful Dead and the Velvet Underground at a theater in Pittsburgh. “I still have the concert poster,” he said. Outside his engineering courses at Duke University, he joined a student group responsible for setting up and taking down concert sets for musicians who appeared on campus.

“Joni Mitchell, Frank Zappa, the Dead—we helped set them up and then we’d watch the shows,” Swartz said. “The work was so similar to what we do on research cruises. It’s just a massive push to get ready then, bam—it’s show time.”

A serendipitous journey

The summer after graduating from Duke, he traveled to Cape Cod for vacation. While waiting in Woods Hole for the ferry to Nantucket, he stood outside a lecture hall reading posters that described ocean science and engineering research.

“This stuff is so cool,” he recalled saying. “The woman next to me said, ‘Are you interested in any of this?’ I told her I would love to work someplace like this.”

The woman, Penny Foster, who still works at WHOI, connected Swartz with the engineering department. He was hired to help repair and develop CTD systems, a conglomeration of instruments that descends into the deep from the side of a ship to measure seawater’s temperature and conductivity (salinity) at various depths.

Six weeks later, he boarded a Russian navy ship with 340 Russians and three other Americans for a three-week research expedition in the North Atlantic. During the next two years, he sailed on seven more research cruises.

Then, following a plan he had mapped before joining WHOI, he left for graduate school at the University of Michigan. After earning a business degree, Swartz spent the next 11 years in management positions at General Electric and Allied-Signal Aerospace.

“I married, had two sons, traveled extensively, and held increasingly responsible management positions, including supervising a business department with more than 70 people and $110 million annual sales,” Swartz said. “But the work was less and less enjoyable.”

By 1992 he had divorced, and was ready for a new professional challenge. He agreed to come back to WHOI to work on the World Ocean Circulation Experiment, a seven-year global project to collect a comprehensive data set from the oceans. The job took him on 12 research cruises worldwide. On some he went as long as 52 days without seeing land.

At home on Cape Cod, his sons John and Mike spent weekends with Swartz. They often joined their dad in his laboratory, where they built spudzookas, a high-powered version of a potato gun. Their best efforts sent potatoes flying 200 yards.

When son John was assigned a science project in grade school aimed at making a household chore easier, Swartz guided him to the dog’s habitually empty water bowl. Together they crafted an alarm that beeped when the bowl’s water dipped too low.

“Growing up, there were all these dads in suits and ties, and then there was my dad, who would show up in a T-shirt with all this insane technology,” said Mike Swartz, now 25 and a Web designer near Boston. “I’ve always loved that he’s offbeat and does his own thing.”

Poise and precision

When the World Ocean Circulation Experiment concluded in 1997, Swartz realized he could no longer count on large, federally funded programs for his salary. He built relationships with scientists and engineers throughout WHOI to develop new instrumentation, improve existing equipment, and take these new tools on cruises for testing and implementation.

Today he sails on research vessels three to six months a year to test, maintain, and help with ocean instruments and technology.

“I always look forward to sailing with Marshall,” said Steve Liberatore, who collaborated with him on the high-speed Data-Link project. “Being at sea is really stressful. You need people who can hold together. There’s nobody better than Marshall at that. Nobody.”

Liberatore recalled Swartz’s reaction several years ago to problems with a deep-sea camera system that Swartz had developed and was testing for the first time.

“The instrument was on deck, all wired and cabled, and ready to survive being towed behind a ship. Finally, the instrument goes over the side using a winch. We then start to drag it 200 meters from behind ship. Before we got too far, we triggered the device to make sure would work. We tried, it fired, and the system locked up. So, we brought it back aboard and tried it again on deck. It worked perfectly.

“Then Marshall is faced with the question of, how do you troubleshoot that?” Liberatore said. “Why wasn’t it working in the ocean, if it worked perfectly on the deck of the ship?”

Meanwhile, pacing nearby was the expedition’s chief scientist, who had spent several years and tens of thousands of dollars having the camera system designed and built, then getting funding to use it at sea.

“I’ve been going to sea 35 years, and I’ve been on over 100 cruises,” Liberatore said. “I’ve seen people lose it from the stress and pressure of trying to get instruments to work. And I’ve seen situations where if anybody has a right to lose it, it’s Marshall. But he just smiles and keeps working.”

Since then Swartz has been asked to build four more of these towed deep-sea camera systems for use by WHOI scientists and others outside the institution.

Working at WHOI, Swartz says, is a state of mind, a way of life. “I didn’t realize when I joined how unusual it was, until I got the experience outside,” he said. “Basically I’m given a fishing license to invent things. This job is doing just what I was doing when I was a kid, except getting paid for it.”

He said he usually doesn’t mind the hours and the time away from home, especially given the new support of an old friend. In early March he married Susie Chapell, his sweetheart from his freshman year at Duke University. Four days after their wedding, he left for a research cruise in the Galápagos Islands.

“Susie,” he said, “met me there when I got off the ship.”

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Ocean engineer Marshall Swartz in his tinkerer's heaven: a lab filled with instruments, tools, work benches, and just enough room to handle equipment and accommodate his dog Little Bear. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- George Tupper and Marshall Swartz working on a CTD rosette prior to a research cruise. CTDs are deployed from a ship to measure conductivity (salinity) and temperature of the water at various depths. Tupper, who retired in 2000 but still works at WHOI occasionally, calls Swartz "a walking encyclopedia willing to work 18 hours a day on behalf of science." (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Marshall Swartz and his dog Little Bear. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- As a boy, Marshall Swartz loved to invent, build, and repair things. (Photo courtesy of Marshall Swartz, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Forty-five years later, Swartz still has the single-minded focus on the engineering problem at hand that often keeps him working late into the night. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- Our eyes on the seafloor

- Unlocking the Earth’s time capsule

- 3 memorable Jason Dives

- How did the ocean remain so quiet during Tonga’s eruption?

- With deep-sea mining, do microbes stand a chance?

- Coming full circle

- 7 Places and Things Alvin Can Explore Now

- The story of “Little Alvin” and the lost H-bomb

- Life at Rock Bottom