Seismic Studies Capture Whale Calls

New software could reveal songs amid the sounds

In November 2012, the California Coastal Commission met to consider a request by Pacific Gas and Electric to study a geologic fault that runs along the central California coast just 300 meters from the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant.

The Shoreline Fault had not been discovered until 2008. With the 2011 Fukushima disaster still fresh in people’s minds, permission to examine it in detail might have been an easy call. But whale conservation groups opposed the study, claiming that underwater airguns to be used in the research would endanger marine mammals.

It was the latest round in a decades-long clash between seismologists and conservationists. The former use airguns to generate sound waves that penetrate and reveal Earth’s structure; the latter worry that those sounds could injure or kill whales and dolphins.

“The thing is, nobody really knows how whales react to airgun shots,” said Dan Lizarralde, a seismologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

In an intriguing twist of fate, he and two WHOI colleagues think they may be able to shed light on that question—using an untapped trove of data from seismic studies.

Ears under water

It turns out that hydrophones (underwater microphones) and seismometers used in seismic studies don’t record just the rumbling acoustic energy from airguns, seafloor volcanoes, and earthquakes. They also pick up the vocalizations of passing whales.

“We’ve been recording whales since the late ‘70s with these ocean-bottom instruments,” said John Collins, a seismologist at WHOI. “In some ways, the whales are a problem, because they make loud sounds and they can obscure an earthquake.” (See “Probing with sound,” below.)

“John had mentioned it to me a couple of years ago,” said WHOI cetacean researcher Laela Sayigh. “I remember him saying to me, ‘I’m getting these sounds. What are the frequencies of blue whale sounds? Could it be them?’ ”

She looked at his seismic records and told him, yes, some of the sounds could definitely be attributed to blue whales. “Then I think he started thinking about it and realized, ‘Wow, this could actually be an amazing data set that could be mined.’ ”

Guess who’s coming to dinner

A plan began to take shape in Collins’s mind. He invited Lizarralde and Sayigh, who did not yet know each other, to join him and his family for Thanksgiving dinner in 2011. The new acquaintances quickly found ample food for discussion: a 2002 Lizarralde-led research cruise during which conservation groups blamed airguns for the death of two whales.

That was the version of events Sayigh had heard, at any rate. She had never been told about the timeline showing that the whales had beached and died when Lizarralde’s ship was still at least 100 kilometers (66 miles) away—and that hundreds of other whales and dolphins, observed by spotters on the ship and in small planes overhead, showed no signs of distress or even of interest in the research ship.

“Talking to Dan was very enlightening, because he had such a different take on it, and one that seemed to me more grounded in fact,” said Sayigh.

They soon realized that data from the cruise had the potential to reveal whales’ behavior before and after the airguns started firing. Lizarralde had used 36 airguns, ramping up the array one gun at a time, the shots about half a minute apart. The hydrophones, some near the surface and some on ocean-bottom seismometers, had recorded during that whole period, including long stretches before any guns fired and the silent gaps between shots.

“That is like the perfect experiment to assess how these animals are responding to airgun shooting,” said Collins.

Excited about the possibilities, the researchers examined data recorded by Lizarralde’s hydrophones. Although they looked very different from the kinds of spectrograms of sounds studied by whale scientists, Sayigh could identify within the data the calls of fin whales and blue whales. A flurry of higher-pitched sounds remains unidentified, and still more might be extracted.

But the potential is clear, especially for seeing what the whales were doing before the shots started and then during the ramp-up to full airgun use.

“Do they change their behavior? Do they go away?” said Lizarralde. “That would be the first thing you could look for, and it would be so easy to do.”

Investment needed

There’s just one small problem: Seismic data had seldom been used for that purpose before, and never in the detail the WHOI researchers have in mind. Recordings from OBS hydrophones could be especially valuable because OBSs are located in large arrays in precise geographical positions, which would allow researchers to track individual whales traveling through the area.

But to pull out whale sounds from the mass of recorded rumblings and present them in a way that allows biologists to distinguish the kinds and numbers of whales present will require sophisticated software that has not yet been created.

That will take money—nowhere near as much as the initial seismic study, but not a trivial amount, either.

It’s what Lizarralde calls a “terraced” project—there was a big investment of effort and money to obtain the seismic records, and now “to do anything beyond this is another pretty decent step,” he said. “It’s not a million-dollar step; it’s about a hundred-thousand-dollar step.”

That’s not a huge grant in ocean science, but as often happens with interdisciplinary studies, this one faces the problem of not quite fitting into the categories under which research proposals are evaluated.

“The biologists will be like, ‘They’re writing a bunch of code and looking at spectrograms; that doesn’t sound like biology to me,’ ” said Lizarralde. “And the geophysicists are going to be like, ‘They’re not going to learn anything about the Earth, so …’ We fall into that crack.”

He and Sayigh recently received seed money from the WHOI Marine Mammal Center that will enable them to take a closer look at some of the data.

A rich vein

The potential for seismic data to enhance our understanding of whales goes far beyond the records from the 2002 study. Software developed for the purpose could be a Rosetta Stone allowing scientists to return with new eyes to collections of data from seismic surveys done all over the world. Since 1999, data from all seismic studies funded by the National Science Foundation and using Ocean-Bottom Seismographs have been archived in the Data Management Center at IRIS, the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology. Those data are available for analysis by anyone with the interest and means.

“The goal is that other people can milk the data for things that you haven’t had time to work on or you don’t even have an interest in doing,” said Collins, who chairs the IRIS Instrumentation Committee. “It costs so much to get these data, the more people that use them, the better.”

The scientists would especially like to see WHOI take the lead on this line of inquiry because, as Collins said, “Somebody else is going to do it. WHOI researchers have provided a huge amount of the data in IRIS. It would be nice for WHOI to say, “Hey look, WHOI showed that you can mine these data for other things.’ ”

Collins and Lizarralde also see a possibility of adapting ocean-bottom seismometers to detect the sounds of more kinds of whales in future studies. They could be outfitted with additional hydrophones that pick up the higher frequencies used by different species and that have something like a voice-activation switch, so they begin recording only when whale sounds are detected. Since the instruments are in place for many months, they could record the comings and goings of several species of whales in the deep sea through the seasons—information biologists currently have no other way to get. And they would do it without bothering the whales.

A fact-based evaulation

For Sayigh, the bottom line is that deciphering the seismic records offers a chance to get closer to answering the question: Do seismic studies harm whales?

Some kinds of sonar are known to harm marine mammals, but evidence that airgun shots endanger them is circumstantial at best, such as a whale washing up on a beach within a few days of a seismic experiment.

As a precaution, federal law requires scientists using airguns to employ marine mammal observers and to cease work if even one whale or dolphin is seen within about a mile of the ship. Such measures did not persuade conservation groups or the California Coastal Commission, which denied permission to do a seismic study near Diablo Canyon.

“To me it seems like a hasty evaluation by the marine mammal conservation community, sort of assuming that these seismic surveys are dangerous to whales,” said Sayigh. “Which may well be a valid assumption, but I think it should be backed up with real data, not just coincidental strandings. I would love to work with Dan and John and use an existing data set that has so much potential.”

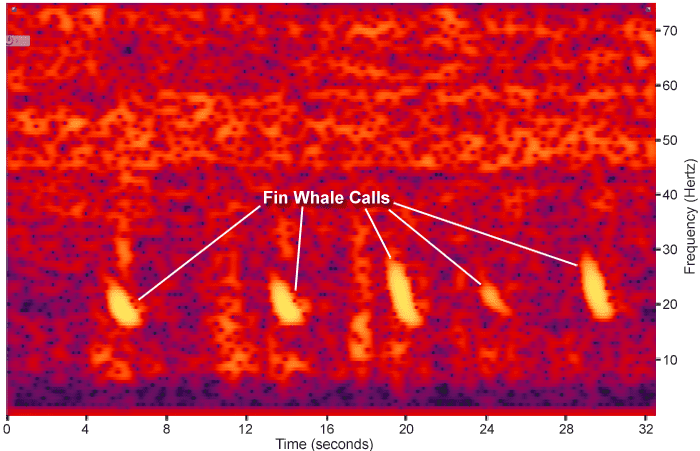

WHOI cetacean biologist Laela Sayigh studies the communication signals of whales and dolphins using spectrograms such as the one shown here. This spectrogram, which was recorded by a hydrophone in Georges Bank, shows calls from two fin whales, one much closer to the hydrophone than the other. Each call lasts about 1 second and falls from about 25 to 30 Hertz to about 17 Hertz. Color indicates the loudness of sounds in these recordings. Violet is less loud, red is louder, and yellow is the loudest. On this spectrogram, sounds other than the whale calls are “background” that may include waves, far distant ships, and other sound sources. (Courtesy of Watkins data archive at the Marine Mammal Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

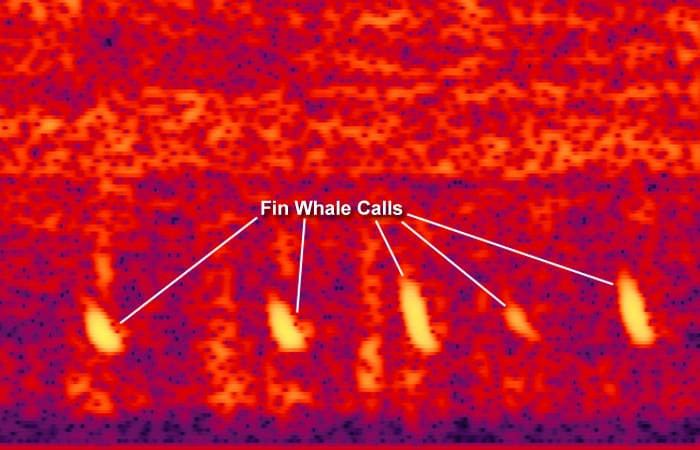

Panel 1. This spectrogram of sounds was recorded by a hydrophone mounted on an Ocean Bottom Seismometer (OBS) in the Gulf of California in 2002. The instruments recorded continuously but this panel shows only the periods when airguns were being fired. Dark blue portions of the spectrogram represent nighttime, dawn, and dusk when the airguns were not being fired. Color indicates the loudness of the sounds, with yellow being the loudest. WHOI researchers Laela Sayigh and Dan Lizarralde have identified the bright yellow signals ranging from about 17 to 30 Hertz as calls from fin whales.

Panel 2. Zooming in on a 5-hour span from Panel 1 shows more detail in the sounds. The brief “blank” periods between intense call activity represent short silences by the calling whale. The source of the sound that hovers around 40 Hertz is not known. The signal near the bottom of the panel is background noise that occurs in almost all recordings from seafloor hydrophones.

Panel 3. Zooming in on 5 minutes from Panel 2 reveals the presence of at least two fin whales, one much closer to the OBS hydrophone than the other. New software could pull out even more data from this and other recordings, allowing scientists to track individual whales and observe their calling behavior before and after airgun shots.

Dan Lizarralde’s 2002 seismic study was funded by the National Science Foundation.

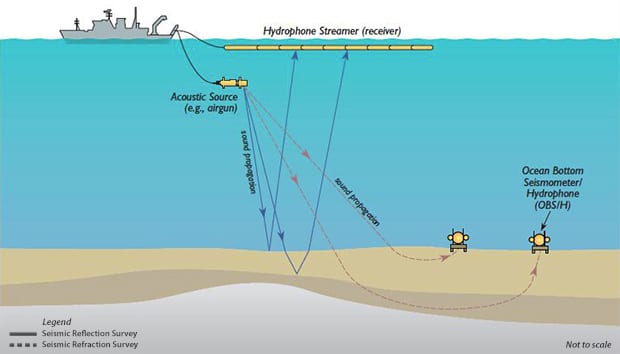

Probing with sound

Illustration courtesy of National Science Foundation

Seismologists rely on sound to learn about the parts of Earth that lie under the ocean. They can map the surface of the seafloor with sonar that uses relatively low-energy sound waves, but to probe deeper, all the way down to the crust and magma far below, they need more powerful tools. Airguns provide low-frequency, higher energy sound waves that can travel through kilometers of sediment and rock.

Their name is accurate in one sense—they build up a charge of compressed air that is released in one big “shot,” creating pressure waves in the water like the waves created in air when a balloon pops. But it is inaccurate in that it suggests a resemblance to destructive weapons such as artillery cannons. Airguns used in seismic studies fire under water, and if you’re on the vessel towing them, a shot is barely perceptible, like the thump of a dinghy hitting the side of the ship.

In a basic seismic survey, a ship tows several airguns and long “streamers” carrying hydrophones, or underwater microphones, that will record the sounds of the shots and their reflections after bouncing off hard structures at or below the seafloor. The airguns fire at set intervals, from every minute to every several minutes, as the ship moves along a set path.

Another kind of study uses instruments anchored to the seafloor. Long lines or grids of Ocean-Bottom Seismometers (OBSs) detect rumblings from natural geologic events such as landslides, volcanoes, and earthquakes. Deploying these OBSs is expensive, and they’re usually left in place to record sound waves and ground motion over several months to more than a year.

Coordinating airgun studies with OBSs in place, rather than either technique used alone, gives seismologists a much better view of the Earth’s structure in an area. Hydrophones towed by the ship pick up reflections of the airgun shots off structures at or beneath the seafloor, and the OBSs pick up the airgun waves after they have refracted through layers of sediment and crust.

The angle of the reflected waves, their strength, and how long it takes them to reach the hydrophones depend on how far the waves traveled and the hardness and density of the materials they encountered. All of that information produces a profile, or image, of the structure beneath the seafloor.

Slideshow

Slideshow

Seismologist Dan Lizarralde and cetacean biologist Laela Sayigh think new software could be developed to extract whale calls from recordings made by seismic instruments. If successful, their work could make seismic records a huge source of data on whale calls. (Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Seismologist Dan Lizarralde and cetacean biologist Laela Sayigh think new software could be developed to extract whale calls from recordings made by seismic instruments. If successful, their work could make seismic records a huge source of data on whale calls. (Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- Seismologist John Collins and geologist Susan Humphris with an Ocean Bottom Seismometer (OBS). OBSs are placed on the seafloor in precise lines or grid patterns and are usually left in place for several months to over a year. The orange plastic "hard hats" house instruments that record ground movements. Many OBSs are also fitted with a hydrophone, or underwater microphone, that records pressure (sound) waves, which may be made by ground movements, ships, or whales. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- How WHOI helped win World War II

- Learning to see through cloudy waters

- A curious robot is poised to rapidly expand reef research

- Whale Safe

- Measuring the great migration

- WHOI breaks in new research facility with MURAL Hack-A-Thon

- Bioacoustic alarms are sounding on Cape Cod

- A tunnel to the Twilight Zone

- The Deep-See Peers into the Depths

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Dan Lizarralde

- Marine Mammal Center A center at WHOI devoted to the study of whales, dolphins, and other marine mammals

- Ocean Bottom Seismometers Find out more about how OBSs work and what scientists can learn with them

- IRIS Website of the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology