Whale Safe

For Mark Baumgartner, Whale Safe is the natural evolution of WHOI’s work with passive acoustics

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

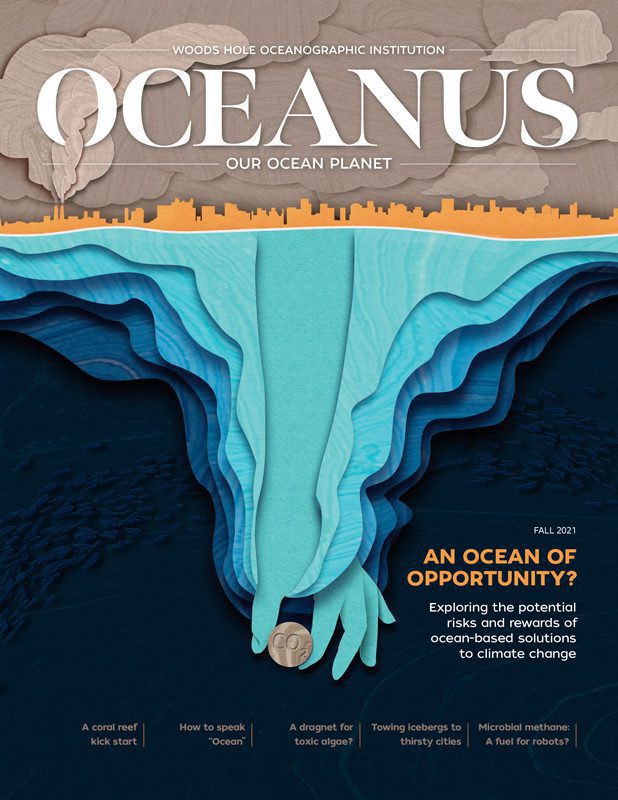

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2021

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2021

Mark Baumgartner is a senior scientist and marine ecologist in the biology department at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who focuses on studying the behavior of the ocean’s top predators. In the last decade, his lab has deployed buoys and gliders armed with passive acoustic recorders to listen for and detect whale movements in areas along the U.S. coast. His lab’s sound research has become the groundwork powering Whale Safe, a new mapping and analysis tool launched in September of 2020 that overlays whale and ship location data to reduce fatal collisions. We sat down with Baumgartner to discuss how passive acoustics studies have evolved over the years at WHOI, and how Whale Safe is a great way to build upon this research.

How different is underwater acoustic technology today than when WHOI first started using it in earnest around the 1950s?

WHOI has had a long and storied history with passive acoustic technology. Early in my career, I remember visiting with a pioneering acoustic scientist at WHOI, Bill Watkins. He had a really big archive room, filled wall-to-wall with magnetic reels of acoustic recordings from the underwater world. Back then, you had to sift through months of detections to finally hear a whale, long after the animal moved on from the recording site. The recorders back then weren’t even submersible. Later on, new recorders got small enough that you could hang them off the side of the boat, then, eventually, on the seafloor for a time. Today, we’re able to take advantage of this explosion of miniaturized electronics with much longer battery life for our marine mammal acoustics work. We’ve also got flash drives and low-power digital signal processors, so we can do a lot more processing.

But, the idea of passive acoustics is the same today as it was back then. You’re basically listening for the sounds animals make. Only now, the real-time detection technology on our buoys and gliders offers us a chance to take action right away.

How does your passive acoustics data help Whale Safe work?

A blue whale's path intersects a freight ship full of goods in October of 2017 off the coast of California. (Photo courtesy of Morgan Visalli, © NOAA)

Since 2013, we had been working on a way to monitor whales and transmit information about the sound they make back to shore to get a sense for which animals were present and where. In California’s Santa Barbara Channel, where the system has been in operation, the buoys send back information about whale presence, while whale-watching ships go out to record sightings that help to confirm those detections. We also use computer models that indicate whale habitat preference, which helps predict the likelihood of whale movement in an area during a given time of year. Finally, on top of all these layers, is vessel location through the AIS (Automatic Identification System), a system that is pretty analogous to GPS tools aboard planes that allow air traffic controllers to prevent collisions.

How will Whale Safe mitigate animal mortality from ship strikes?

Whale Safe is a concept that hasn’t been tried anywhere before. And when I say that, I mean whale and ship traffic data hadn’t previously been made into user-friendly, publicly available information that can be used to hold shipping companies accountable for their corporate sustainability policies. If a company says, “We really care about the environment,” now the public can say, “Okay does your supply chain involve shipping companies that share those same corporate values?” and this is a system to check that.

We’re not trying to tell individual ships that they need to be careful because there is a whale directly ahead. The system is more designed to sound a warning bell: “Hey there are whales around.” Similar to passing speed limit signs with flashing lights near a school in the morning—you’re being warned that the likelihood of a collision is going up in that area, so you may want to be vigilant and slow down.

Ultimately, how do you hope to see the system used in the future, now that it’s been released to the public?

I’d like to see Whale Safe adopted elsewhere. The system builds on a really great program that was first developed by NOAA here on the East Coast and takes it one step further. Whale Safe is allowed to report on the good and the bad; which shipping companies are doing well and cooperating with the voluntary speed reductions, and which are not.

My colleagues in Canada have already been using this same passive acoustic technology, and the Canadian government has opted to close off fishing areas and slow ships down in shipping lanes based on triggers from gliders equipped with our WHOI-developed technology. It would be great to have a coast-wide system whereby we monitor for North Atlantic right whales throughout their range. I personally don’t want to live in a world where animals are going extinct because of the things that we do in the ocean.

Whale Safe is funded by the Benioff Ocean Initiative out of the University of California Santa Barbara