Bioacoustic alarms are sounding on Cape Cod

How a WHOI/IFAW study on dolphin sounds could help decrease mass strandings on the cape

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Spring 2020

This article printed in Oceanus Spring 2020

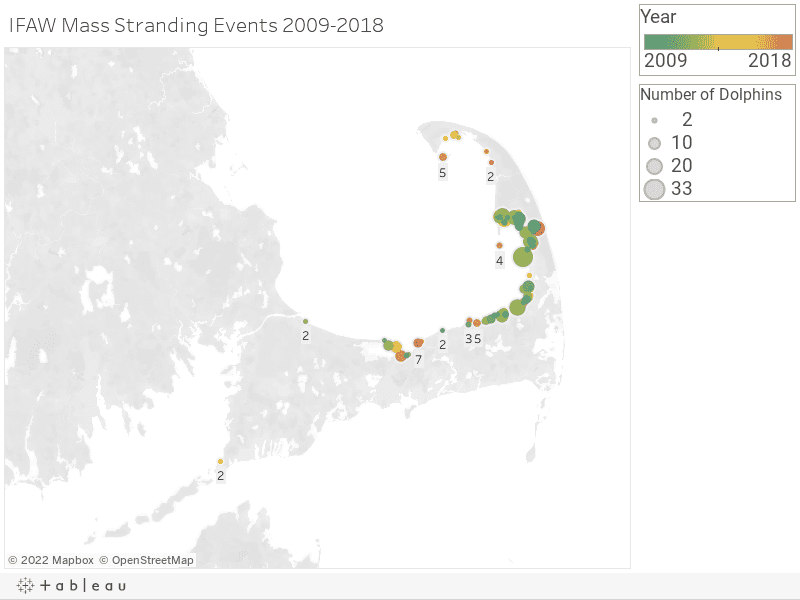

The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) and its Marine Mammal Rescue Team in Yarmouth, Massachusetts have responded to a record high of more than 464 marine mammals stranded on Cape Cod since January this year. Researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) believe patterns from animal sound data may be the key to curbing these numbers.

For those sing-songy dolphins that captivate many, sound is more than play, it’s survival. Like humans calling in the night, dolphins use their high-pitched whistles to note their position in the water, or if they’re unlucky, on shore.

“It’s like calling your name out to your friends,” says Laela Sayigh, an animal behaviorist at WHOI. “When dolphins and whales are stressed, the most important thing is for them to stay in touch with their group mates.”

Back in the early 2000s, Sayigh’s colleagues, including fellow WHOI marine mammal expert Michael Moore, former northeast stranding coordinator Dana Hartley (NOAA) and necrospy coordinator Andrea Bogomolni (Cape Cod Stranding Network), suggested that there may be detectable changes in the vocalizations of distressed dolphins and whales that are about to strand on Cape Cod’s beaches. With funding from Woods Hole Sea Grant, Sayigh saw an opportunity to finally explore what Moore and her other colleagues were talking about.

In 2014, her team installed a passive underwater recorder, or soundtrap, in Wellfleet Harbor, a place notorious for mass strandings. Working with IFAW data, Sayigh was able to observe nuances in recorded whistles around the time of a stranding and contrast them with the sounds of individuals not in danger of the phenomenon.

What they discovered was an exciting correlation: a cacophony of distress calls recorded time and time again before documented stranding events. With enough data to codify this pattern, they could program an alert system to initiate response teams at the onset of a stranding event.

“It was certainly exciting from a biological perspective,” adds Sayigh.

But for members of IFAW’s marine stranding team, this research couldn’t come soon enough.

The Hook Within a Hook

From a bird’s-eye view, Cape Cod has an iconic fish hook shape. Indeed, the area’s appearance has become the symbol of countless vacation-themed shirts about deep-sea angling and summer fun. But for conservationists at IFAW, Wellfleet Harbor is the barb on that hook—and not in a pleasant way.

Drastic tidal changes of more than 13 feet over shallow sandbars make the narrow bay a virtual trap for the unwitting marine visitor. Add to this the rush hour of boat traffic, migratory patterns, and inclement weather, and it’s no wonder dolphins and whales can’t avoid this sandy fate.

For members of IFAW’s Marine Mammal Rescue Team, Cape Cod’s preeminent stranding response group, the work has never been easy. Everything from common dolphins and minke whales, to injured gray, harbor and harp seals, all take turns winding up on shore.

In the past 20 years since the response team’s inception, they have always expected each species to strand on a seasonal schedule, typically following migratory patterns. Such rotations made it a manageable endeavor for the modest six-to-eight-person response teams. But times have changed.

“Usually it’s a cycle for each species – often there is one species where strandings peak for the year,” says Misty Niemeyer, the stranding coordinator for IFAW. “One year will be higher for harbor porpoises, another for harp seals… this year it’s everything at once.”

Of all these marine victims, Sayigh was most interested in studying the sounds of highly social creatures that regularly strand together. After all, more individuals should mean louder, clearer and more frequent signals. And no two species would be more suited for this study than the common and Atlantic white-sided dolphins.

In early 2012, more than 200 common and Atlantic white-sided dolphins stranded during an 80-day stretch, forcing IFAW into a 24/7 operation.

“We got to the point where we would wake up and just drive to Wellfleet,” says the organization’s research coordinator, Kathryn Rose. “We wouldn’t even wait for a call.”

In the past ten years, IFAW has logged 139 mass strandings involving the two species, totaling more than 668 individuals. More than 71 of these events occurred during WHOI’s research period. It was clear: the species’ proneness to mass strand made them the most suitable subjects to observe. Identifying and logging every dolphin whistle, however, would be a lofty goal.

The Art of Whistle Detection

In their nearly four years of research, Sayigh’s team collected more than 6,287 hours of recordings. Altogether, that’s more than 261 days of audio.

The tools they used are modest to say the least: a pair of headphones and an audio visualization called a spectrogram, generated by a software program called Raven. Chief among Sayigh’s other assistants were former students Sam Walkes from Bowdoin College and Seth Cones of Ohio University (and a current doctoral student in the MIT/WHOI joint program) who in one summer scanned through a big chunk of the data collected between 2014 and 2018.

Laela Sayigh tags dolphin whistles collected from Wellfleet Harbor on her computer using a program called Raven (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“There’s no [reliable] way of putting in files of whistles from [whale or dolphin] species and training the computer to look and count for them,” says Cones. “Until then, it’s all manual.”

Cones, who began the project as a summer intern in 2017, is just now finishing the final year of data analysis. In that time, he’s tagged and analyzed more than 124 hours of the aquatic calls, scientifically known as signature whistles. On a monitor, these whistles appear like scribbles on an Etch-A-Sketch, but with an unmistakable pattern and cadence, some with high peaks and low valleys.

“We have to use visual representations of the sound, because our human ears can’t manage those higher frequencies,” notes Sayigh.

Frame by frame, 30 seconds at a time, Sayigh, Walkes, Cones and a cadre of supporting scientists scrolled through the endless static of Harbor ambience, humming boats, and curious wildlife to count the rare marks of whistles—a sound needle in an auditory haystack.

Sayigh even incorporated a small group of budding scientists from the Girls in Science program (video here) to help teach them about marine mammal vocalizations, while also expediting the search for these elusive calls.

Some days of audio were so dense with sound that they required an additional four days just for analysis, recalls Cones. In spite of this, the cohort still maintains an untampered excitement. Now zooming in, any feature from the peaks, valleys or breaks in each whistle could be another clue into the early warning signs of a potential stranding. One important difference in any of these patterns could mean saving scores of dolphins.

“There’s got to be something else in [the dataset] that we’re missing,” notes Cones. “It’s like a puzzle.”

The Future of Conservation

By combining soundtraps with computers that are coded to recognize the auditory cues of mass strandings, Sayigh believes we may be close to a future where an SMS text alert could notify rescue teams at IFAW to respond preemptively to strandings.

“I’m optimistic and hopeful that [the data] will help with mass stranding event detection, but we’d need more data to feel comfortable,” says Sayigh. This will mean identifying more than just occurrences of these whistles, but how far apart they occur from one another, and the window of opportunity to act once a detection is made.

And if there’s any one salient thing to know about marine mammal rescues, it’s that they’re time-sensitive.

On shore, marine mammals suffer the alien effect of gravity—their weighty figures sinking into the sharp edges of shells in the mudflat. The added stress of chilling winter winds or the pounding summer sun make an already uncomfortable experience a living horror. In large enough sizes, these mass strandings can overwhelm even the most experienced rescue teams.

On the clock to relocate sometimes dozens of individuals at a time—each weighing several hundred pounds—it is inevitable that some animals do not survive. In the last decade, nearly 20 percent of mass stranded dolphins found alive succumbed to exhaustion or sickness and died, or had to be euthanized.

“A lot of what we learn is from the animals that don’t make it,” says Niemeyer. “But compassion fatigue is a real thing.”

For Niemeyer, an alert system means the difference between herding live animals out of the bay with skiffs and motor boats, or sampling scores of dead ones in the Yarmouth facility’s mobile necropsy lab trailer.

But this isn’t the first time IFAW has stood behind bold conservation initiatives.

In 2010, NOAA approved the organization’s plan to affix tags to individually stranded dolphins scheduled for release. The tags reported the dolphins’ position by satellite, and IFAW’s teams discovered the individuals had indeed survived and reunited with their pods.

“We debunked the myth that animals couldn’t meet up with their pod and survive [after a stranding],” says Niemeyer.

More than anything, Niemeyer stresses the importance of public awareness. For her and Sayigh, Cape Cod can be ground zero for an automated alert system that could benefit other mass stranding hotspots worldwide—places like New Zealand and Australia, and even parts of the U.K., where dolphins and whales have been beaching for millennia.

For now, it seems the ethos of Cape Cod—it’s undeniable connection to marine life—continues to drive support for WHOI’s and IFAW’s collaborative research, sometimes in strange and subtle ways.

In 2015, IFAW representatives attended Wellfleet’s annual Oyster Fest to promote knowledge of strandings in a place commonly afflicted by the issue. It was poignant that the attendees, including research coordinator Kathryn Rose, had to leave to meet Niemeyer in response to a stranded dolphin along the harbor sandbar. An early departure was, after all, an appropriate (albeit unplanned) advertisement of IFAW’s work.

Back then, Cape Cod’s lone highway was clogged with carefree festival-goers coming and going from Wellfleet. But the kindness of several police officers called in by the festival’s organizers made for an unconventional scene: the blare of police sirens, making way for a gurneyed dolphin in a trailer.

“There are so many cumulative impacts on these species. Some are obvious like entanglements in fishing gear and vessel strikes, but a lot of them are not so obvious… there’s ocean noise, climate change, contaminants, algal blooms, I could go on and on,” says Niemeyer. “There’s a lot we can’t fix – we’ll never eliminate strandings – but this could have a significant impact and save more animal lives.”

The bioacoustics research project was made possible with funding from the Woods Hole Sea Grant in Woods Hole, Massachusetts and collaborative support from the International Fund for Animal Welfare in Yarmouth, Massachusetts. This story's map visualization was rendered using data generously provided by IFAW's Marine Mammal Rescue Team. To learn more about Laela Sayigh's research on bioacoustics check out the Girls in Science Program video above, where she was featured as a leading scientist and mentor.