Seafloor Reconnaissance Reveals Hidden Dangers Off Antarctica

Science team discovers potential navigation hazard near research station

For five frigid weeks in April and May 2005, a team of scientists and engineers sat in inflatable boats off the coast of the western Antarctic Peninsula, steering clear of sharp rocks and sea ice, enduring cold feet, and anxiously watching the weather and a variety of animals that swam near the small boats—including humpback whales, penguins, and especially leopard seals.

“There were several leopard seals right by us that were as long as the 14-foot boat,” said WHOI biologist Scott Gallager. “We saw one leopard seal toss a penguin in the air and catch it as it came down.”

One early morning, members of another research group witnessed two large leopard seals attack a fur seal with such force that they nearly cut it in two. The team was mindful of being in low, air-filled craft susceptible to sharp teeth. “Everyone kept an eye on them,” Gallager said, “and backed off carefully, if a seal approached.”

The team’s objective was to meticulously chart the ocean floor near the U.S. Palmer Research Station—to help select a suitable site for a new underwater observatory that they will install next year. But in the process, dodging dangers, they serendipitously discovered another potential danger that research ships had unknowingly been dodging for years.

Making detailed seafloor charts

To make a new seafloor chart of the area, the team—Gallager, co-principal investigator Vernon Asper of the University of Southern Mississippi, and WHOI engineers Keith von der Heydt and Gregory Packard—used a portable depth sounder with GPS, deployed over the sides of the boats, and a WHOI-built REMUS autonomous underwater vehicle equipped with sonar. Doggedly following a fine-scale grid pattern in and out of coves on the rugged shoreline, they took more than 180,000 depth readings at 50- and 100-foot spacing in waters extending several kilometers around Palmer.

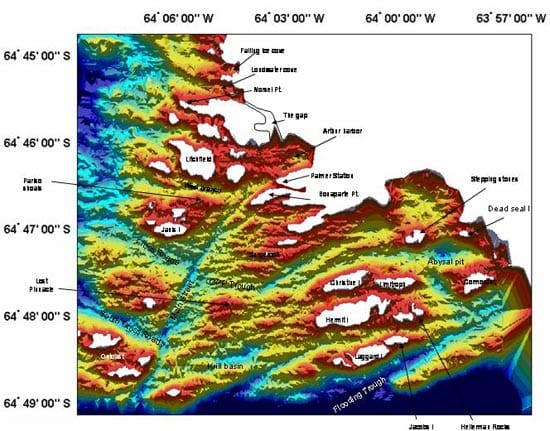

The new chart is the most detailed and comprehensive ever compiled for this area, and the first made in 50 years. It shows deep, glacier-carved troughs extending from land to seafloor and several likely sites for the new long-term observatory, known as the Polar Remote Interactive Marine Observatory (PRIMO). The observatory, which will continuously monitor currents, animal life, seawater chemistry, and other aspects of the fertile marine ecosystem, must be installed in waters deep enough to avoid being scoured by icebergs, yet close enough to Palmer Station to be connected by a power-and-data-carrying electrical and fiber-optic cable.

The chart also revealed a huge surprise: a number of previously unmapped submerged rocks, including a set of sharp rocky pinnacles that pose potential hazards to ships. Some of the pinnacles rise nearly 100 meters (330 feet) from the sea bottom to just 6 meters (20 feet) below the sea surface. The rocks are close to routes generally taken by ships traveling to and from Palmer Station.

Charting a new course for ships

“Ships navigate in and out of Palmer by sighting on visible rocks and sticking to the route they have always used,” Gallager explained. “These rocks couldn’t be seen, and no one knew exactly where they were.”

The previous chart of the area was made in the mid-1900s by single, widely spaced depth soundings. Some underwater hazards were marked on an even earlier chart, but the team found that chart to be off by nearly a mile, and no sure guide to ships.

“When you think of all the ship traffic that has passed through the area over the years and the often hostile weather conditions,” Gallager said, “you realize how skillful and lucky the crews have been.”

Personnel at Palmer Station and the captains of the U.S. polar research ships Nathaniel B. Palmer and Laurence M. Gould were were interested in the new findings. The researchers left copies of their chart with the station and each ship, and the Gould and Palmer now use modified routes to and from the station.

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation, Office of Polar Programs.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- WHOI engineers Keith von der Heydt (right) and Greg Packard conduct a bathymetric survey of the sea floor near Palmer Station, Antarctica, encountering weather, wildlife, and unexpected navigation hazards. (Photo by Scott Gallager, WHOI)

- Greg Packard, in an inflatable boat, prepares to launch an autonomous underwater vehicle called REMUS (Remote Environmental Monitoring UnitS), to measure ocean- bottom depths in a pre-determined area and pattern around Palmer Station, part of a 5-week survey resulting in a new chart of the area. (Photo by Keith von der Heydt, WHOI)

- Several inflatable boats were used during the seafloor survey and needed to be taken out of the water almost daily to avoid ice damage. The Laurence Gould is in the background. (Photo by Keith von der Heydt, WHOI)

- A computer generated map of the seafloor around Palmer Station shows deep troughs scoured by receding glaciers. The map is based on more than 180,000 soundings taken from the inflatables. (Map generated by Scott Gallager, WHOI)

- Looking out from Palmer Station, Antarctica, where the cable for the PRIMO observatory will be installed. (Photo by Keith von der Heydt, WHOI)