Rapid Response

Scientists scramble for rare opportunity to catch an underwater volcanic eruption in action

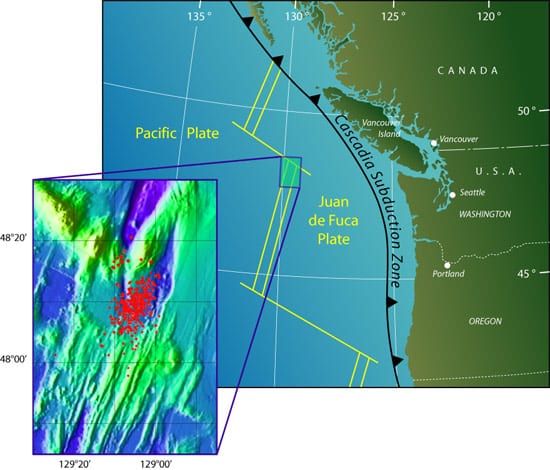

The earthquakes were coming fast and frequent, as many as 50 to 70 an hour. On the morning of Sunday, Feb. 28, undersea hydrophones began detecting the most intense swarm of earthquakes to occur in the last three years along the Juan de Fuca Ridge, about 200 miles off the Pacific Northwest coast.

Within the next 36 hours, signals from 1,498 earthquakes were relayed to onshore computers as scientists sent a flurry of e-mail messages to discuss the likelihood that a volcanic eruption was occurring on the bottom of the northeastern Pacific Ocean. By Tuesday, they were mobilizing researchers, shipping tons of research equipment overnight to Seattle, arranging to use and load a research vessel that luckily was docked nearby, and catching last-minutes flights—all for the rare opportunity to witness an undersea volcanic eruption triggered by earthquakes.

Such deep-ocean eruptions are not infrequent, happening dozens of times annually around the world. In fact, the eruptions are part of an ongoing, fundamental process that continually creates new seafloor crust. This crust spreads out from its volcanic sources to create new ocean basins and reshape Earth’s face throughout the planet’s history.

But the vast majority of those earthquakes and eruptions occur far out to sea, where there are no instruments to detect them. Even if they were detected, they are usually too far to reach quickly by ship.

A rare opportunity

“Oceanographers have a built-in handicap because we so rarely have an opportunity to view undersea earthquakes and eruptions happening in real time,” said geologist Dan Fornari, director of the Deep Ocean Exploration Institute at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “We’re missing a piece that helps us understand how Earth formed and constantly reshapes.” Fornari helped mobilize a camera system for the quickly assembled expedition, launched March 5, to try to capture unprecedented data on undersea eruptions as they are happening.

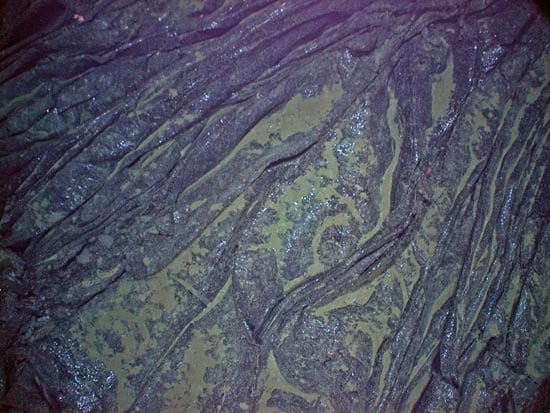

Since 1993, the National Science Foundation Ridge 2000 Program and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration have funded six such rapid-response expeditions offshore the Pacific Northwest, where an undersea surveillance system provides signals from earthquakes. On five expeditions, “we have seen some smoking guns,” said oceanographer Robert Dziak, who monitors offshore activity from his laboratory at the Hatfield Marine Science Center at Oregon State University. These included chemical plumes in the water that indicate the presence of hydrothermal vents, as well as freshly erupted lava, which looks glassy and black on the seafloor.

“Each time we go out we get a little bit closer to seeing things happen in real time,” said Dziak. “We still haven’t caught it within a few days. But this was our fastest time getting out there yet.”

Fast-moving scientists

Oceanographic expeditions typically take three to twelve months to plan and organize. The most recent trip, organized by oceanographer Jim Cowen at the University of Hawaii, came together in six days.

“It was pretty frantic, like an oceanographic SWAT team,” said geologist Bill Chadwick of Oregon State University, an expedition participant.

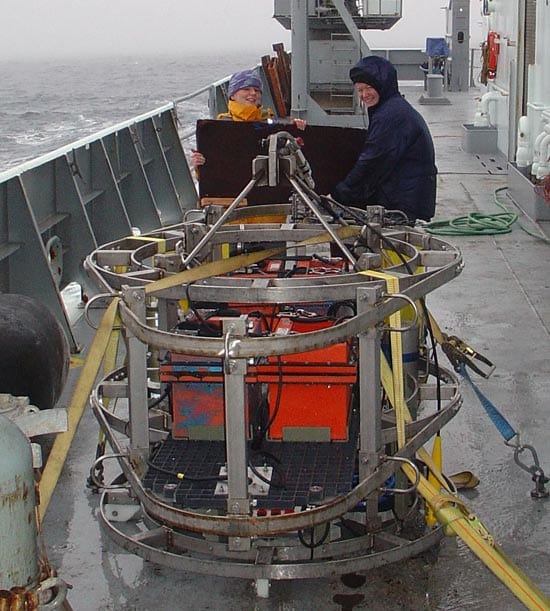

Research equipment, much of it shared between U.S. oceanographic research institutions, was identified, shipped, and re-assembled. R/V Thomas R. Thompson, one of 28 oceanographic research ships operated in the U.S—and a vessel typically booked months in advance—happened to be available in Seattle. Crew members, including the captain and two dozen engineers and technicians, upended their time ashore to run the vessel and support science work. Twenty scientists from five states and Canada dropped research projects and family obligations for a 20-hour cruise to the earthquake locale.

Marshall Swartz, a research associate in WHOI’s Physical Oceanography Department, said he didn’t sleep for four nights as he helped to arrange for the various parts of a towed undersea camera system to be sent from Hawaii, California, and Massachusetts for use on the vessel.

Once on board, he and WHOI postdoctoral fellow Rhian Waller spent hours at shipboard computers remotely guiding the camera system at specified heights above the seafloor to map the area for evidence of volcanism. Unlike geologists on land, oceanographers had to contend with thousands of tons of seawater just to position their instruments.

By the end of the cruise, scientists determined that the quakes occurred too deep beneath the surface to send fresh lava to the seafloor. Still, “the experience was worth the hustle,” Swartz said. Hundreds of photos, dozens of chemical samples, and sonar information will be analyzed in the months ahead, offering more clues and insights into deep-sea activity.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- SWIFT SCIENTISTS—WHOI postdoctoral fellow Rhian Waller (left) and University of Washington graduate student Deb Glickson were among the scientists who tried to witness an undersea volcanic eruption in action. During the expedition to the Juan de Fuca Ridge aboard the R/V Thomas R. Thompson, Waller used a towed camera system, shown in front, to find evidence of volcanism. (Photo by Marshall Swartz, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- EARTHQUAKE SWARM IN PACIFIC NORTHWEST—On the morning of Sunday, Feb. 28, undersea hydrophones began detecting the most intense swarm of earthquakes to occur in the last three years along the Juan de Fuca Ridge, about 200 miles off the Pacific Northwest coast. Each red dot represents an earthquake epicenter. Within five and a half days, undersea hydrophones detected 3,742 earthquakes. (Illustration by Jayne Doucette, WHOI Graphic Services)

- LIFE ON THE SEAFLOOR—Though scientists did not see evidence of erupting lava, they did find other things on the seafloor during their March visit to the Juan de Fuca Ridge. Long-armed, bright-colored starfish called Brisingids, common in the deep ocean, live near corals and filter-feeding fan worms. (Credit: WHOI)

- SEARCHING FOR FRESH LAVA—Scientists responding to undersea volcanic eruptions are looking for evidence of fresh lava. This lava, photographed on the Galapagos Rift in 2002, was estimated to be less than 10 years old. One way scientists place an age on lava is by looking at its surface. As lava ages, it loses its glassy black luster. (Credit: WHOI)

Related Articles

- Can seismic data mules protect us from the next big one?

- Lessons from the 2011 Japan Quake

- Lessons from the Haiti Earthquake

- Seismometer Deployed Atop Underwater Volcano

- Worlds Apart, But United by the Oceans

- Oceanographic Telecommuting

- In the Tsunami’s Wake, New Knowledge About Earthquakes

- Ears in the Ocean

- Earthshaking Events

Featured Researchers

See Also

- NOAA Acoustic Monitoring Ocean Seismicity

- The SOund SUrveillance System (SOSUS)

- Ears in the Ocean: Hydrophones reveal a whole lot of previously undetected seafloor shaking going on from Oceanus magazine

- Mid-Atlantic Ridge Volcanic Processes: How Erupting Lava Forms Earth's Anatomy from Oceanus magazine

- The Deep Ocean Exploration Institutute: Investigating Earth's dynamic processes from Oceanus magazine

- WHOI Towed Camera System

- Time Critical Studies, Ridge 2000 Program, National Science Foundation