Oceanographic Telecommuting

'Virtual' chief scientist directs a research cruise without leaving land

From her office at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Debbie Smith is guiding the 279-foot research ship Knorr as it maps the seafloor about 1,000 miles east of Venezuela. During her 20 years as a geophysicist, she has been chief scientist of a research cruise four times, directing and coordinating scientific activities aboard ships. But this week, she did it for the first time from shore, in her self-described role as ‘virtual’ chief scientist.

Oceanographers such as Smith typically spend weeks and even months at sea gathering data on the oceans. The development of new system called HiSeasNet now allows scientists to communicate from shore to ship in real time.

So without leaving her office, Smith watched as her computer received the bathymetric, magnetic, and gravity information she needs to learn more about a series of unusual deep-sea earthquakes off South America. With a few keystrokes in an e-mail sent to Knorr’s captain, Smith even adjusted the ship’s course.

“Oops, that’s not where we should be going,” Smith said, frowning at a tiny icon of Knorr as it inched westward across a seafloor map of the Atlantic on her computer screen. After consulting large, multicolored bathymetric charts spread over her lab table, she sent a message, then relaxed minutes later when she saw that Captain A.D. Colburn had made the adjustment and the ship tracked according to her research plan.

Improving technology

For years, going to sea for science meant leaving the shore behind. In the 1980s and 1990s, communications meant the occasional old-fashioned radio exchange and costly phone calls using a maritime satellite. Expensive, low-speed e-mail messages were sent and received in batches, and the transfer was limited to three or four times daily (at a rate of about $10 per minute).

“It may surprise people to learn that we haven’t had instant e-mail and continuous Internet connectivity from research ships in the world’s oceans,” said Bob Detrick, a marine geologist and Vice President for Marine Facilities and Operations at WHOI. “Until very recently, working remotely like Debbie is doing would have been cost-prohibitive.”

Communicating from ship to shore and back again has been a desire for ocean researchers for more than 30 years,” said Stephen Miller, head of the Geological Data Center at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which uses HiSeasNet to remotely monitor the acquisition of shipboard data from two vessels operated by Scripps.

First, shipboard antennas had to be designed to fit on relatively small research vessels (compared to larger cruise ships or military vessels). Antenna also had to accommodate the vessels’ pitch and roll while keeping a solid signal connection with satellites in space. Then computer software and modems were developed to compress and bundle gigabytes of data and transmit information more efficiently. At the same time, the cost of renting bandwidth from a commercial satellite dropped.

Cost differences can be significant, said Steve Foley, a computer engineer at Scripps. For example, a ship operating with HiSeasNet may incur an expense of seven cents per megabyte of data transferred. That’s compared to $34 per megabyte without the new communications system.

Smith said she wanted to go to sea, but family commitments kept her on shore. Because of HighSeasNet, she could still gather data. “As chief scientist, I’d be making these same sorts of decisions at sea,” Smith said, “only here I don’t have the rocking and rolling, and I don’t have to sleep in a bunk at night.”

Growing use of HiSeasNet

HiSeasNet is now used on four academic research vessels operating in the Pacific, Foley said. Service to two others in the Atlantic began in April. Three more are expected to come online by the end of the year.

“I think it’s going to be wildly popular,” said Jim Akens, a senior engineer at WHOI who worked with fellow engineer Barrie Walden to prepare Smith’s computer for HiSeasNet use. Akens said he has already received inquiries from other interested scientists, including a researcher from Scripps who plans to work from shore when Knorr travels to Antarctica later this year.

Peter Lemmond, a software engineer from WHOI who is working on Knorr this week, said HiSeasNet does give oceanographers flexibility. Still, he doubts that its use will replace the at-sea experience.

“Even with better, faster, cheaper communications, nothing beats face-to-face discussions,” Lemmond said in an e-mail sent Saturday from the ship. “And coordinating our 24/7 operations at sea with daily life on shore is a challenge.”

Smith’s intimate knowledge of the seafloor, along with the many months she has spent on ships, is indispensable in making the system work. Like chief scientists on any cruise, Smith’s days (and nights) on land have been spent collaborating with colleagues, consulting maps, making decisions, dashing off e-mails, and worrying about the accuracy of the data being collected.

“I’m still as stressed as I would be on sea,” Smith said. “Still, it’s a big plus that I can leave work at five, have dinner with my family, then log in to check the ship’s progress from my home computer.”

Funding for Debbie Smith’s research at WHOI was provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF). Funding for HiSeasNet comes from NSF, the Office of Naval Research, and individual system operators, including: WHOI, Scripps, University of Rhode Island, University of Hawaii, and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Slideshow

Slideshow

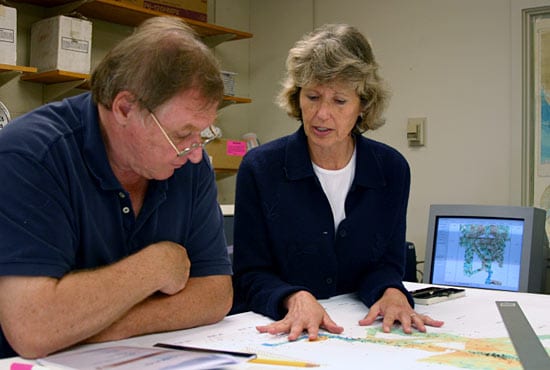

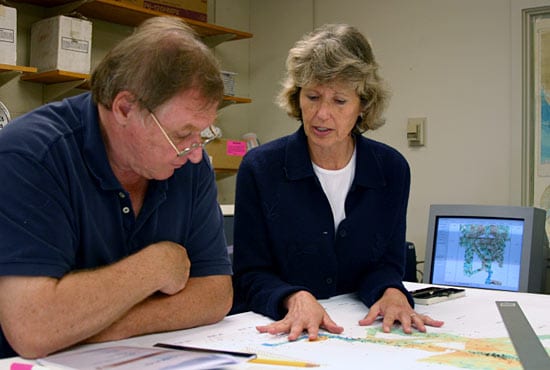

In her lab in Massachusetts, geophysicist Debbie Smith discusses her deep-sea mapping research with fellow geophysicist Hans Schouten. In the background, a computer shows the track of research vessel Knorr as it gathers the bathymetric, magnetic, and gravity information Smith needs to learn more about a series of unusual earthquakes off South America. (Photo by Amy Nevala, WHOI)

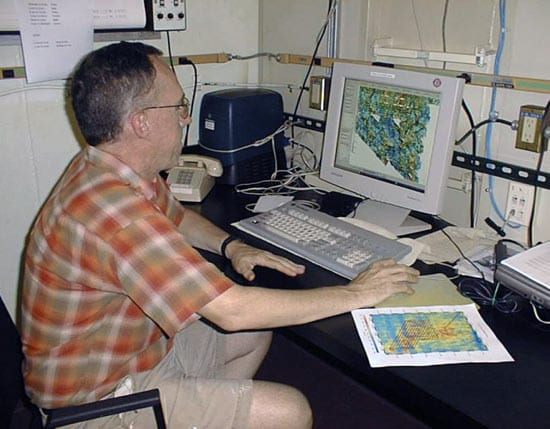

In her lab in Massachusetts, geophysicist Debbie Smith discusses her deep-sea mapping research with fellow geophysicist Hans Schouten. In the background, a computer shows the track of research vessel Knorr as it gathers the bathymetric, magnetic, and gravity information Smith needs to learn more about a series of unusual earthquakes off South America. (Photo by Amy Nevala, WHOI)- Peter Lemmond, a software engineer from WHOI who is on R/V Knorr, looks at bathymetric maps of the seafloor about 1,000 miles east of Venezuela. On shore, Smith receives identical data, which became possible with the recent development of HiSeasNet. (Photo by Amy Simoneau, WHOI)

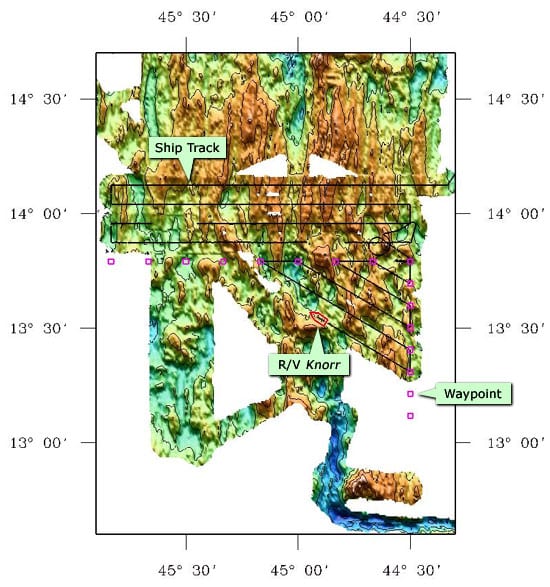

- R/V Knorr follows specified points as it tracks back and forth like a lawnmower to make maps of a mid-ocean ridge offshore South America. (Illustration by Danielle Fino and Debbie Smith, WHOI)

- HiSeasNet, a satellite communications network that provides continuous Internet connections for oceanographic research ships, is now used on six American research vessels operating in the Atlantic and Pacific, including the R/V Knorr. (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution photo)

Related Articles

- Can seismic data mules protect us from the next big one?

- Lessons from the 2011 Japan Quake

- Lessons from the Haiti Earthquake

- Seismometer Deployed Atop Underwater Volcano

- Worlds Apart, But United by the Oceans

- Rapid Response

- In the Tsunami’s Wake, New Knowledge About Earthquakes

- Ears in the Ocean

- Earthshaking Events

Featured Researchers

See Also

- HiSeasNet: Internet for Oceanographic Ships at Sea

- WHOI Marine Operations: R/V Knorr

- Deborah K. Smith, Research Homepage

- Cyberinfrastructure Component The UCSD division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) in partnership with Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC).