Once More Unto the Rift

Expedition explores deep-sea animal life via live TV stream

In the beginning, there was the Garden of Eden. It was a lush primordial oasis of life, bursting with exotic life forms. Now, scientists have embarked on a research expedition to return to the Garden.

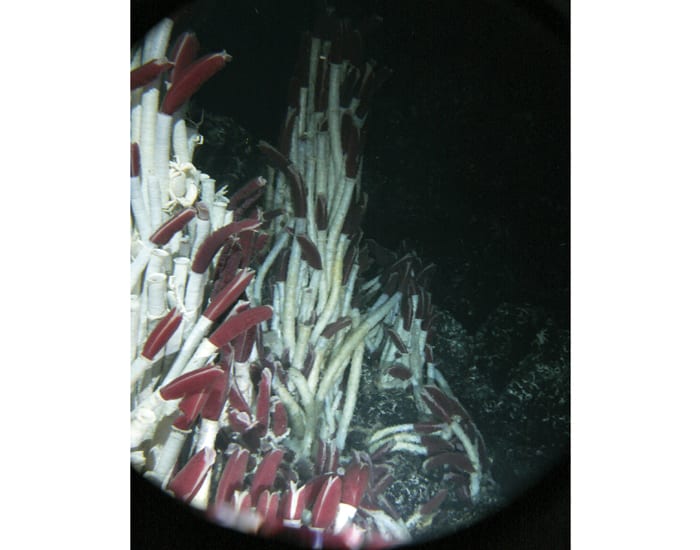

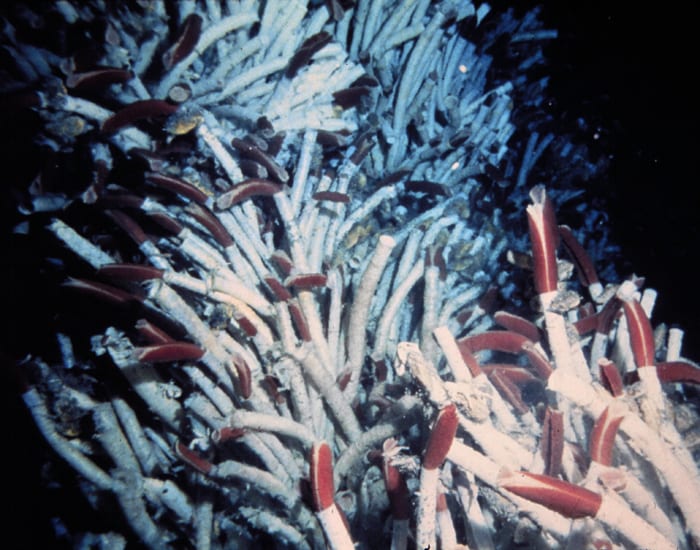

The expedition does not involve time travel. This Garden of Eden is on the bottom of the ocean. It was named by scientists diving in the submersible Alvin near the Galápagos Islands in 1977. They were astonished to see fields of slender, 6-foot-tall, white tubes with the blood-red tips of worms peeking out. Like flowers atop tall stems, they swayed in the shimmering breeze of warm fluids venting from the seafloor. The discovery of life thriving in the absence of sunlight and nourished by chemicals in the vent fluids revolutionized understanding of how and where life could exist, and raised new ideas about the origins of life on Earth.

On June 9, the research vessel Okeanos Explorer, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), set out on the 50-day expedition to search for deep-sea communities along the Galápagos Rift. The rift is a segment of the mid-ocean ridge, the chain of volcanic undersea mountains that meanders across the entire globe at the borders of Earth’s great tectonic plates. Beginning next week, scientists aboard the ship will deploy Little Hercules, a tethered remotely operated vehicle that will transmit high-definition video live from the seafloor.

Since vent life was found on the Galápagos Rift, oceanographers have found that various animal populations live in different regions of the seafloor. “You can think of these deep-sea communities along the mid-ocean ridge like cities connected by an interstate highway system,” said Tim Shank, a deep-sea biologist at WHOI who will be aboard Okeanos Explorer. “The populations in San Diego, Minneapolis, Boston, and Miami are quite different, and so are animal populations on different segments of the mid-ocean ridge and even along the same segment.”

Along a section of the mid-ocean ridge called the East Pacific Rise, which separates the Pacific Plate to the west and the Cocos Plate to the east, scientists have found more than 160 species of worms, crustaceans, and mollusks. The Galápagos Rift is the border between the Cocos Plate and the Nazca Plate to the south. At the Garden of Eden and seven other vent sites discovered between 86°W and 89.5°W along the Galápagos Rift, however, scientists have found fewer than 60 species, but many of these have not been seen anywhere else.

For more than two decades, scientists have theorized about the reasons for this diversity. One hypothesis is that the Hess Deep, a chasm at the juncture of the Pacific, Cocos, and Nazca Plates that plunges 9,000 feet deep, might act as a formidable barrier blocking the dispersal of larvae of deep-sea animals, Shank said.

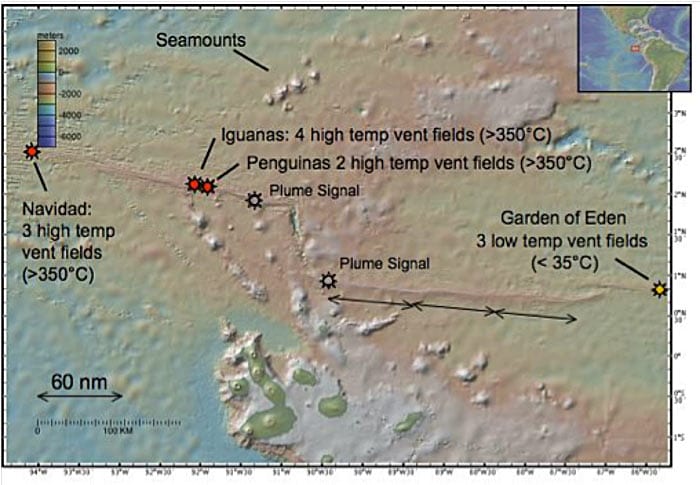

A second leading hypothesis is that animal communities are determined by different types of vents found in different areas. On the East Pacific Rise, scientists have found “black-smoker” vents, which billow out powerful jets of dark, mineral-rich fluids that reach temperatures of 350°C (660°F) under deep-sea pressure. No such sites have been discovered yet along the Galápagos Rift, where fluids with temperature less than 35°C (95°F) waft from the seafloor.

On a 2005 research cruise, however, Shank and colleagues found evidence of three areas with black-smoker vents to the west of the Garden of Eden. Scientists christened them the Navidad, Iguanas, and Penguinas Vent Fields. In the center of this area, at 91°W, a large fault offsets the Galápagos Rift like the middle segment of a “Z.” The newly found high-temperature vent sites are north of the zag; and the older low-temperatures vent sites are on the other side of it to the south. Does this fault act as a border between different volcanic activity, a barrier for larval dispersal, or both?

The 2005 expedition offered only a brief encounter with and tantalizing glimpses of animal life at the new black-smoker vent sites, including giant tubeworms and dinner-platter sized clams and mussels. To get a much closer look, the 2011 expedition will revisit these sites with Little Hercules. Via its fiber-optic cable attached to the ship, scientists will be able to control the vehicle’s navigation precisely. And like a mechanical optic nerve, the tether will transmit real-time images to scientists.

Then Okeanos Explorer will proceed east to revisit Rosebud, Garden of Eden, and other previously studied sites southwest of the 91°W fault. Not only do vent sites differ by their location, they also change over time, Shank said. In 2002, he was aboard an expedition to revisit a vent site first discovered in 1977 called Rose Garden. Scientists never found it again and concluded that a volcanic eruption had paved it over with fresh lava.

Not far from the original Rose Garden site, however, atop the new lava flow, Shank and colleagues discovered new adolescent communities of clams, mussels, and tubeworms, some no more than an inch tall. They named the site “Rosebud.” On the same voyage, they found a vent site they named “Calyfield,” because it was dotted with giant clams called Calyptogena magnifica. A formation from an extinct high-temperature vent was nearby.

Okeanos Explorer will explore what has happened at these sites—or what may be happening. In an e-mail Shank sent June 29 just before he departed to meet the ship, he wrote: “After the last three days of surveying, it looks as if the rift from Calyfield to at least Rosebud has become very active. In fact, given the data, we may have black smokers in an area that has not had them before. Honestly, we don’t know at this point.”

The expedition aims to find out.

This expedition is being funded by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- In 1977, WHOI scientists and colleagues were astonished to find lush communities of life thriving without sunlight on chemical-rich fluids venting from the seafloor. The scientists called this site, filled with 6-foot-tall tubeworms, "Garden of Eden." Another site nearby was called "Rose Garden." (Kathleen Crane, NOAA)

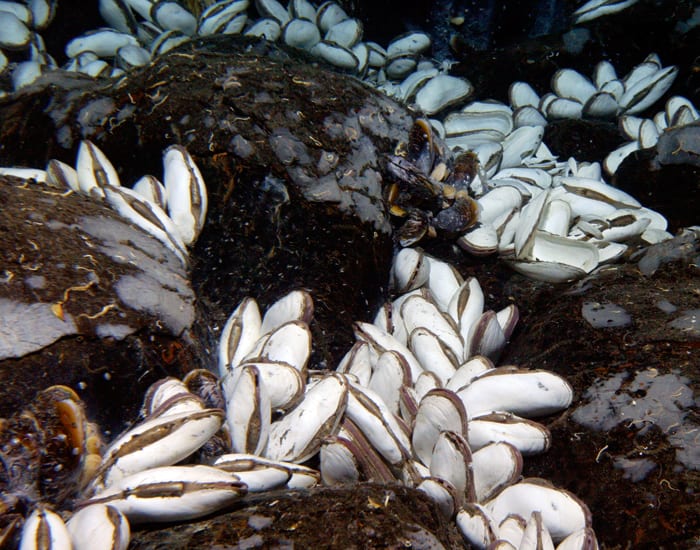

- When scientists returned to the Galápagos Ridge in 2002, they found that "Rose Garden" had probably been paved over by fresh lava in an undersea volcanic eruption. But they discovered a new site, with juvenile tubeworms, which they called "Rosebud." (Photo courtesy of Tim Shank, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- This vent site, dotted with giant clams called Calyptogena magnifica, was discovered in 2002. It is called "Calyfield."

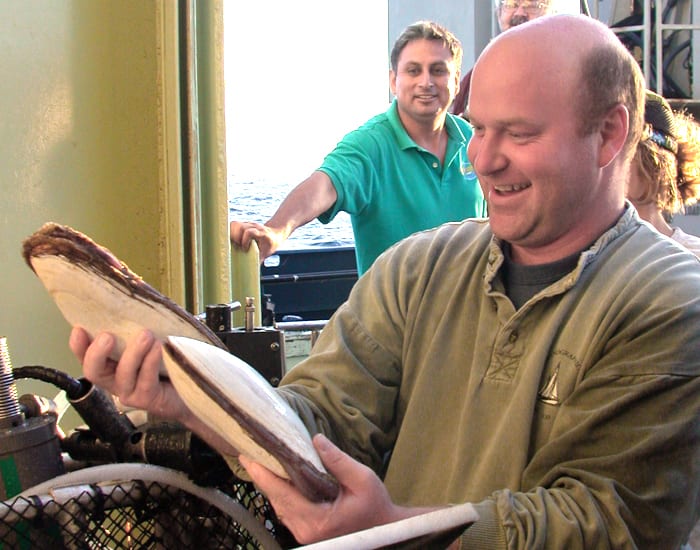

- Tim Shank, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, collects samples of giant clams retrieved by the Alvin submersible during the 2002 expedition to the Galápagos Rift. Shank returned to the area in 2005 and is back again on a new voyage in July 2011.

- In 2005, scientists found another vent community on the Galápagos Rift. Considering its shape and continuing a tradition, they named it "Rose Bowl." (Photo by Dan Fornari, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- During the 2011 expedition to the Galápagos Rift, scientists hope to explore recently-discovered vent sites (Navidad, Iguanas, and Penguinas) east of a large north-south fault at 91°W that separates segments of the rift. They will also visit longer-known sites such as Garden of Eden, which lies east of the fault, and investigate signals from chemical plumes from as-yet unknown vent sites. (Map courtesy of Tim Shank, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- he 2011 expedition is aboard Okeanos Explorer, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program INDEX-SATAL 2010)

- The expedition will use the remotely operated vehicle Little Hercules. Via its fiber-optic cable attached to the ship, scientists will be able to control the vehicle’s navigation precisely. And like a mechanical optic nerve, the tether will transmit real-time images to scientists aboard the ship. (NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program INDEX-SATAL 2010)

- If all goes well, live video images from the deep sea will be transmitted via Little Hercules and Okeanos to scientists in command centers on shore. (NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program INDEX-SATAL 2010)

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Dive & Discover Expedition to the Galapagos Rift in 2002

- NOAA Ocean Explorer Website

- On the Seafloor, a Parade of Roses from Oceanus magazine

- The Evolutionary Puzzle of Seafloor Life An article on deep-sea biogeography by Tim Shank from Oceanus magazine

- Tim Shank's Lab