Five extreme places to do ocean research

Whether they’re under the ice at the furthest poles or hovering above the ocean’s deepest volcanoes, these researchers get the job done.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

Ocean research presents a unique set of challenges, whether scientists are contending with harsh weather, extreme temperatures, or the occasional volcano. Here are five of the most extreme places WHOI researchers are exploring to learn more about our oceans.

Under Arctic Ice Sheets

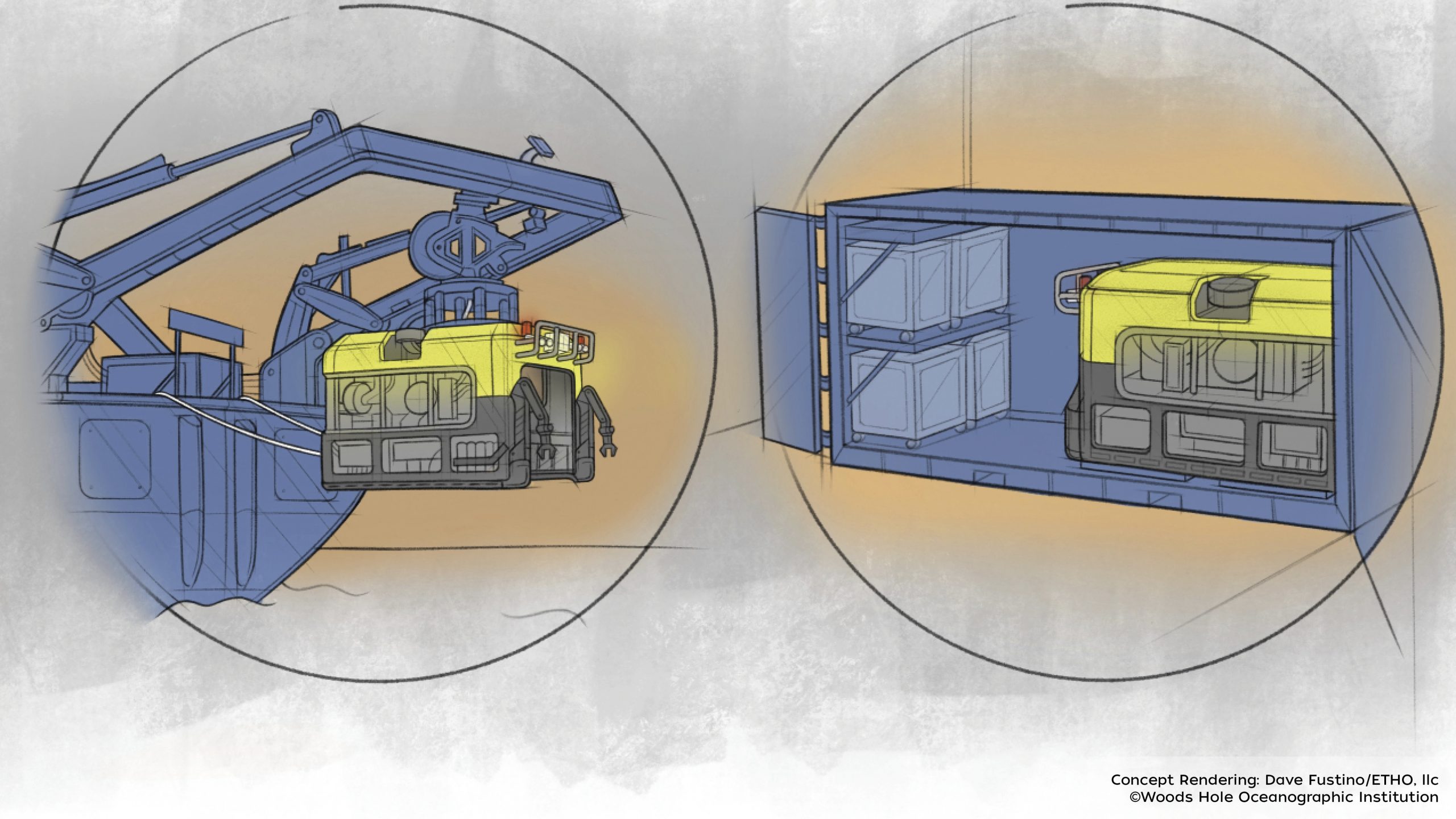

The Arctic Ocean is an ever-changing environment. Calving glaciers drop massive chunks of ice into the sea and the resulting icebergs float freely. The ice pack grows and shrinks with the seasons. And there is life underneath it all. Researchers board powerful icebreaking ships to explore this region, but to study the ecosystem, they need to reach far under the ice. Engineers at WHOI designed Nereid Under Ice to be their eyes and instruments. The remotely operated vehicle can navigate under the ice, away from the disruption of the icebreaker, and send back data from a chilly realm teeming with algae, copepods, and jellies.

Irminger Sea

Wedged between southern Greenland and an underwater mountain range extending south of Iceland, the Irminger Sea is one of the windiest places on Earth. Storms pass through every few days and Greenland’s steep mountains twist and concentrate the prevailing winds into powerful gusts that stir up huge waves. In this tumultuous region, warm ocean waters cool and sink, driving circulation patterns that affect the global climate. To study in this area, WHOI researchers have had to design buoys capable of withstanding the challenging conditions (it took several tries) and carefully time their cruises to be able to deploy and retrieve subsurface equipment between storms.

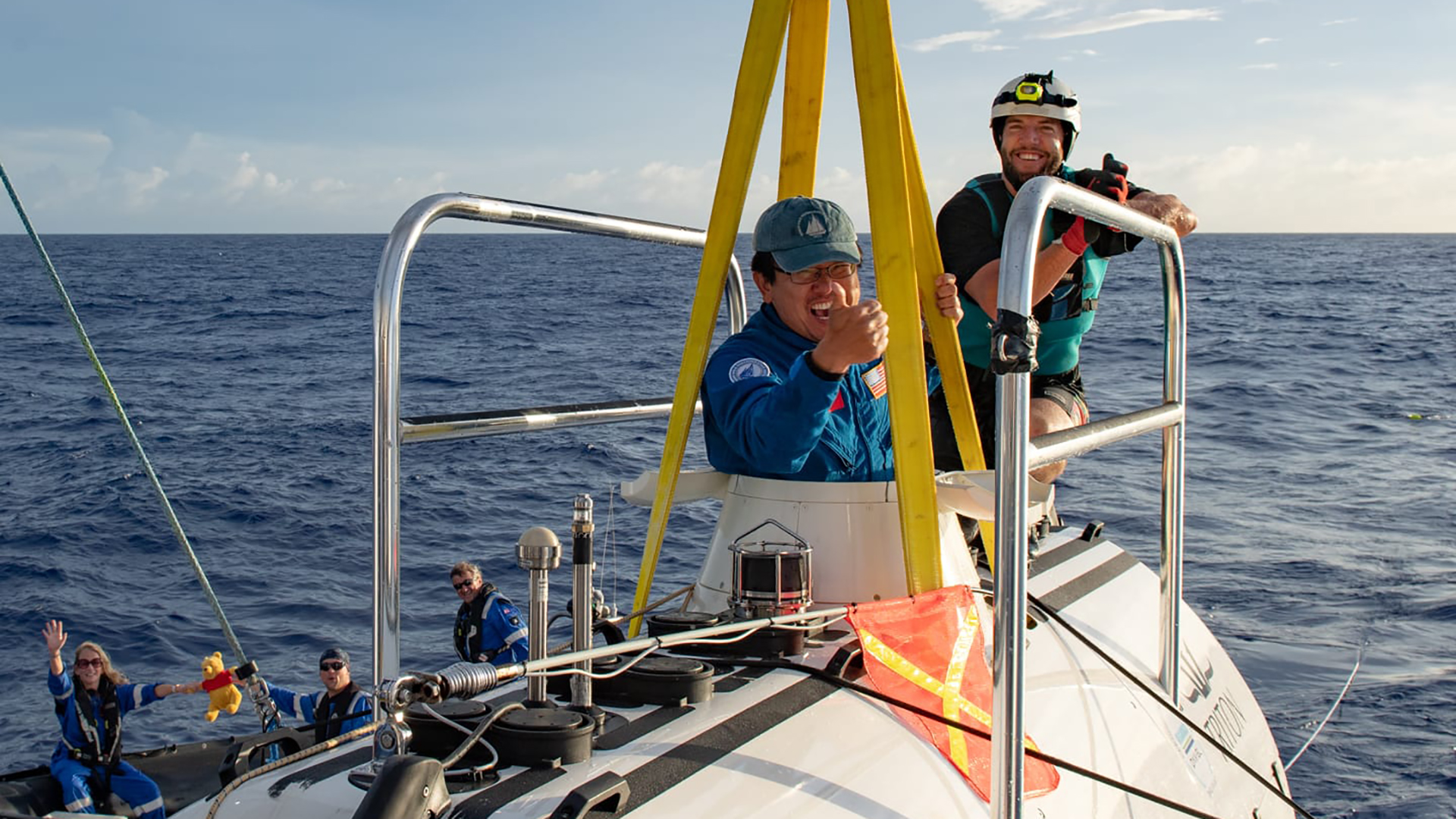

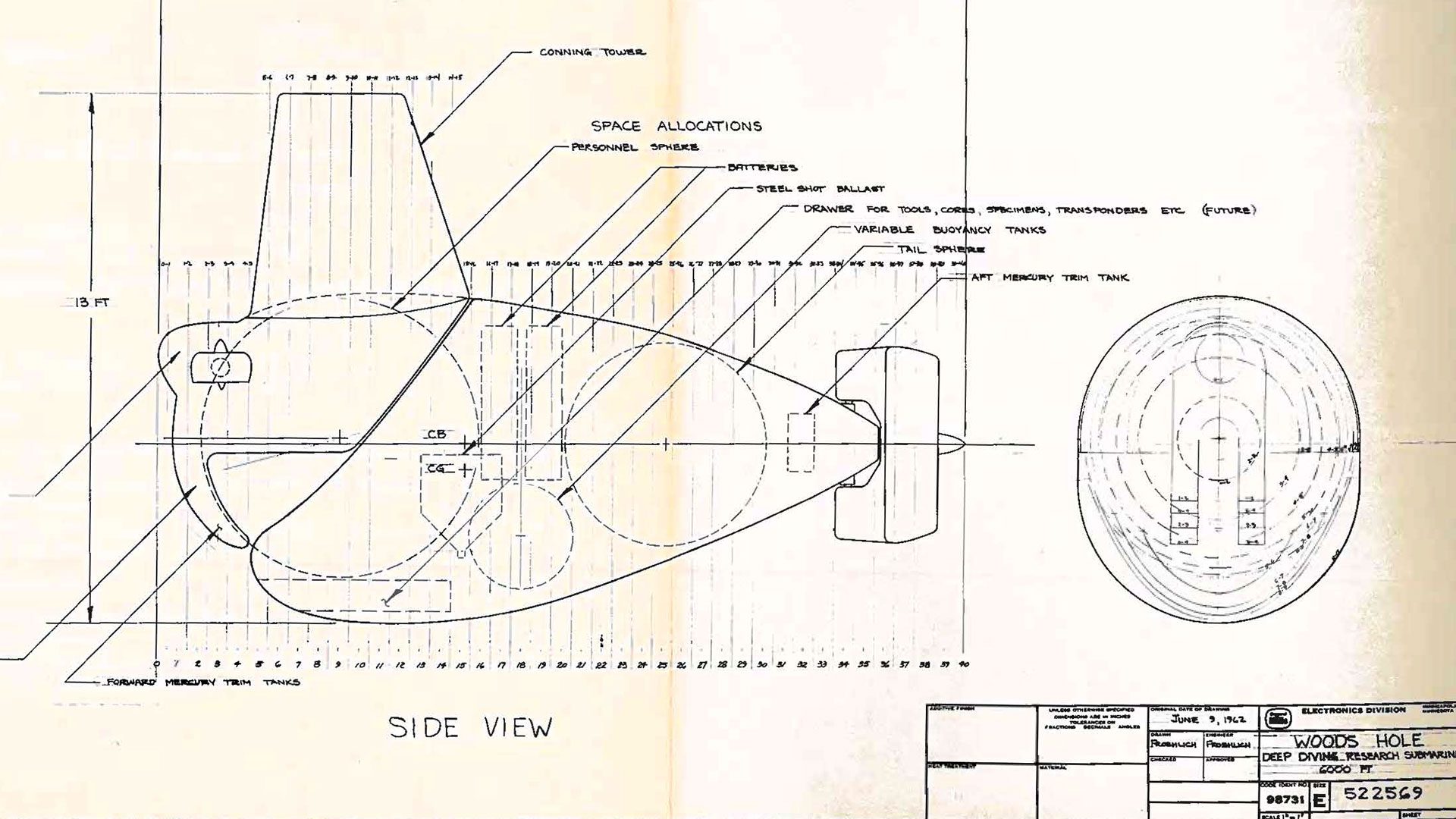

Challenger Deep

If you put Mount Everest at the bottom of Challenger Deep, its peak would still be more than a mile from breaking the surface of the ocean. As far as we know, this crevice in the Mariana Trench is the deepest place in the ocean. At the bottom, nearly seven miles from the surface, the pressure is 1000 times higher than at sea level. It’s also pitch black and nearly freezing. This may not seem particularly inviting to most people, but for Ying-Tsong Lin, an acoustics researcher at WHOI, the 10-hour trip was an opportunity of a lifetime. The extreme pressure and dense water change how sound travels. Lin, who was the first person of Asian descent to visit Challenger Deep, conducted experiments to measure these changes and potentially improve acoustic measurements in the future.

Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is the southernmost sea on the planet, tucked into a wide bay in Antarctica. This remote area is surrounded by a vast desert of ice and snow, punctuated by volcanos, and extends under an ice shelf roughly the size of Spain. Temperatures at the nearby McMurdo Station have dropped as low as -50 degrees Celsius in the dark winter days, but most researchers conduct their work in the summer months when the sun never sets and temperatures occasionally rise above freezing. WHOI researchers are studying the seabirds and other creatures that thrive there, as well as how climate change is reshaping the landscape.

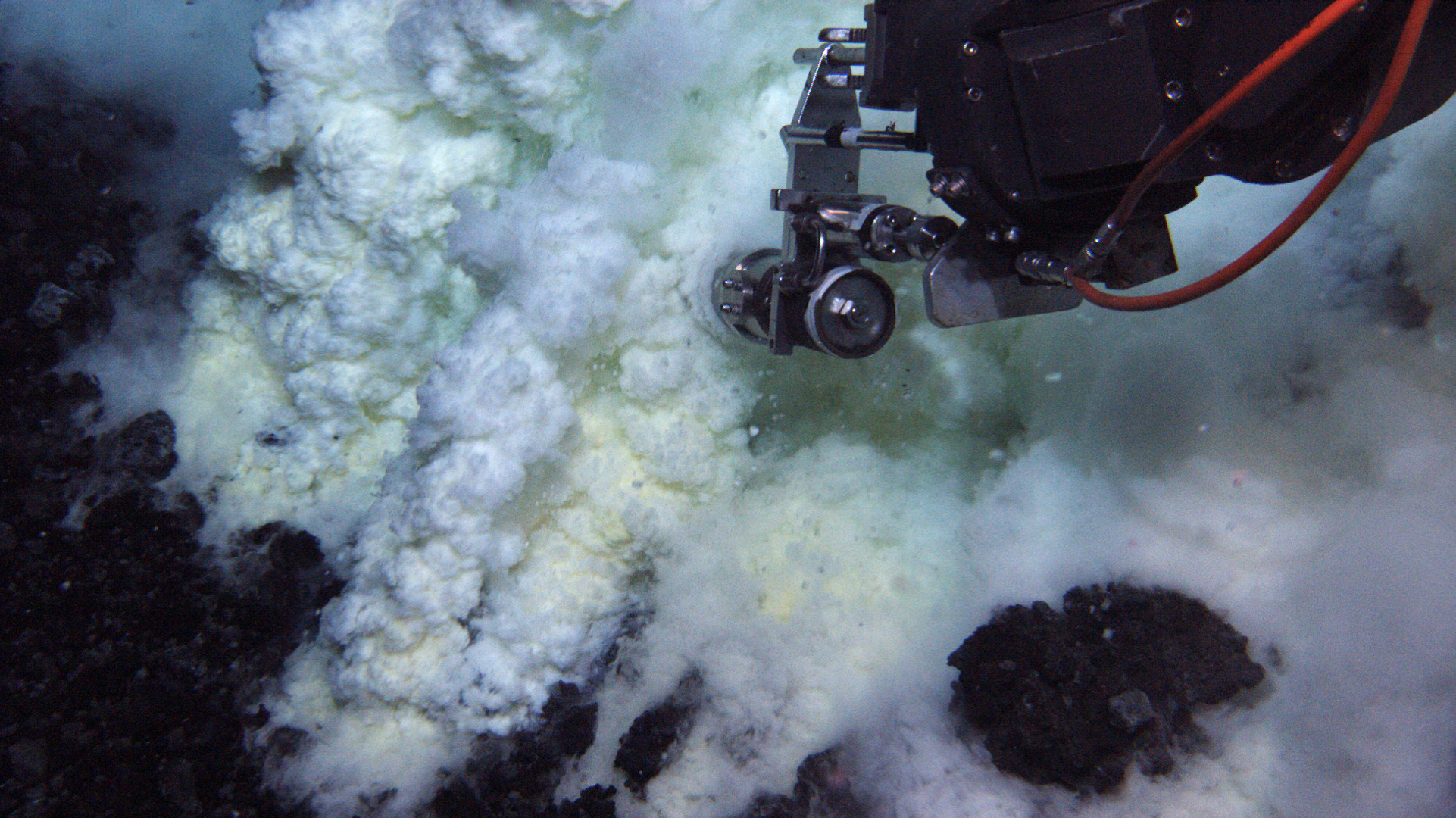

Deep-sea Volcanoes

It’s never a good idea to stand next to an erupting volcano. Even under water, where heat is dispersed more quickly and debris is not flung as far, an active volcanic landscape is full of hazards. But ocean scientists want a front row seat for these violent events that shape the sea floor and create habitat for unique deep-sea creatures. Enter Jason, a remotely-operated submersible attached to a six-mile tether that lets scientists explore the seafloor without leaving the deck of a research vessel. In 2009, WHOI researchers used Jason to take the first video of an active undersea eruption during a cruise in the western Pacific.