On the Seafloor, a Parade of Roses

A third generation of scientists finds the third generation of hydrothermal vent sites

Tim Shank was a 12-year-old shortstop on North Carolina ballfields in 1977 when scientists in the submersible Alvin made a startling discovery near the Galápagos Islands: Lush communities of animals thrived on the sunless seafloor, living on chemicals venting from the volcanic ocean bottom.

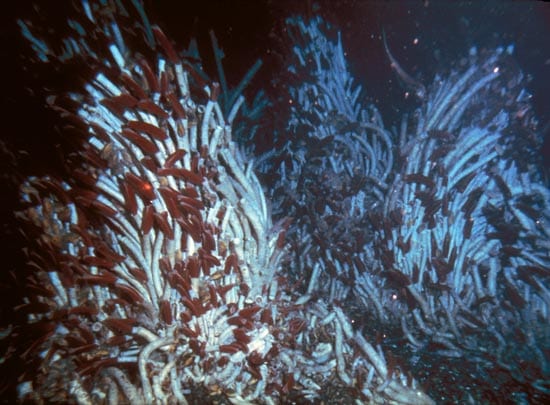

Two years later, Shank still wasn’t paying much attention to the news when returning scientists, looking out Alvin’s view ports, saw rows of slender white tubes with blood-red worms poking our of their tips, The scene resembled a field of giant long-stemmed roses, and so scientists christened the vent site “Rose Garden.”

“It wasn’t until college that the animals and geology of hydrothermal vents really caught my eye,” Shank said. As he pursued a career in marine biology, Shank began learning about the famous Rose Garden, where scientists first learned of the amazing ways that vent animals adapt to live in their extreme environment.

In 2002, now a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Shank co-led an expedition back to Rose Garden to see how the animals, geology, and fluid chemistryhad changed since scientists last visited it a decade before.

But over several Alvin dives, it became disappointingly apparent to Shank that Rose Garden had been paved over by erupting lava. His dashed hopes were partially allayed when, nearby, expedition researchers found tiny tubeworms, thumb-sized mussels, and other new life that probably arose in the aftermath that destroyed Rose Garden. In homage, they named this new vent site “Rosebud.”

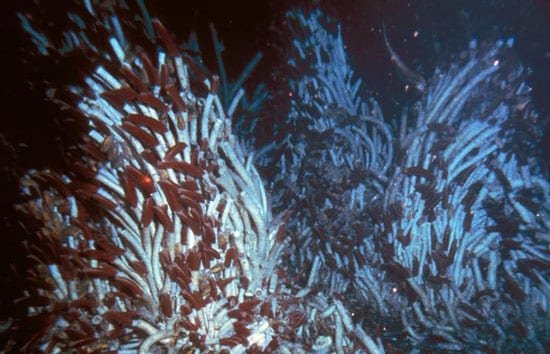

This spring, Shank returned to Rosebud to continue learning about the conditions that foster life at vent sites and that shift the demographics of animals living in vent communities. Celebrating his 40th birthday at sea, Shank found that the communities at Rosebud were at full bloom, maturing into midlife.

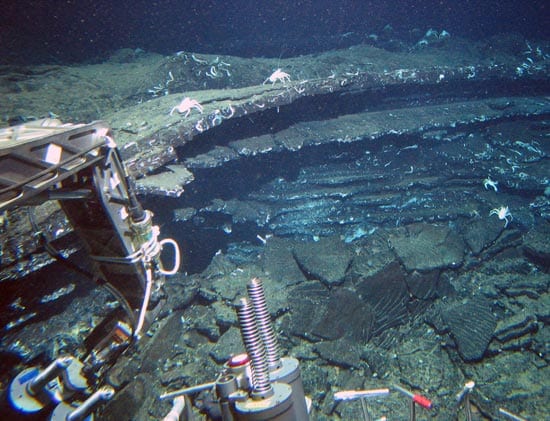

Then, during the 2005 expedition’s final dive, researchers in Alvin came across a concave, ring-shaped area on the seafloor about 10 meters (30 feet) in diameter. White crabs crawled its perimeter, and anemones and mussels populated its center. The shape of the vent site—and its lineage—suggested what the expedition would name it: “Rose Bowl.”

“It was one of those times when you say, ‘Oh, if I only had one more dive, I know I could learn so much more,” said WHOI volcanologist Adam Soule, who was in Alvin when Rose Bowl was found. “I’m already looking forward to going back someday.”

So is Shank.

Support for Shank’s expedition to the Galápagos Rift came from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Ocean Exploration Program, the WHOI Deep Ocean Exploration Institute, and the National Science Foundation.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Biologist Tim Shank (in hat) shows off a white crab captured during an expedition to the Rosebud vent field this spring. He explained to geologist Susan Humphris and WHOI guest Dan Dubno that the crab is a scavenger that can grow to about the size of a hockey puck. ((Photo by Amy Nevala, WHOI) )

- The ?Rose Garden? vent site at the Galapagos Rift was so named in 1979 because of its thickets of tubeworms, which looked like long-stemmed red roses. (Photo by Kathleen Crane, NOAA)

- Tiny tubeworms poke out of the seafloor at the Rosebud vent site when it was discovered in 2002. (Photo by Tim Shank, WHOI)

- Tubeworms, some up to 1.8 meters (6 feet) in length, come into view through Alvin?s viewport during a dive in June 2005 to the vent field Rosebud. (Photo by Dan Fornari, WHOI)

- A vent site found during an expedition to the Galapagos Rift in June 2005 had a concave, ring shape about 10 meters (30 feet) in diameter. White crabs crawled its perimeter, and anemones and mussels populated its center. The shape of the vent site?and its lineage to previously found sites called Rose Garden and Rosebud?suggested what the expedition would name it: ?Rose Bowl.? (Photo by Adam Soule, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)