Ocean acidification is no big deal, right?

WHOI's Jennie Rheuban discusses the very real phenomenon of an increasingly acidic ocean and the toll it's taking on marine life

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

Some people argue that ocean acidification isn’t an issue of concern. After all, they say, the ocean isn’t actually acidic. There is some truth to that. On the pH scale, which runs from 0 – 14, pure water lands at a neutral 7. Ocean water has a pH of 8, so it is slightly alkaline, or basic.

But that argument misses the point. Acidification refers to how the pH has changed over time: ocean water has gotten more acidic over the past 200 years, dropping by about 0.1 pH units since the start of the Industrial Revolution. That doesn’t sound like much, until you consider that the pH scale is logarithmic. Water with a pH of 7 is ten times more acidic than water with a pH of 8. When the pH changes by just 0.1 units, that’s a 26% increase in acidity and a huge change for marine life that depends on stable ocean chemistry.

Why is the ocean becoming more acidic? Burning of fossil fuels has released large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The ocean’s surface absorbs some of that carbon dioxide, which reacts with water to create carbonic acid. “That’s a natural chemical process,” says WHOI marine chemist Jennie Rheuban. And it happens under normal pH values. Carbonic acid is an acid because it releases hydrogen ions into the water. “The more hydrogen ions, the more acidic it is,” she says.

WHOI research specialist Jennie Rheuban culturing oysters at sites with varying water qualities at Oregon Beach in Barnstable, Mass. The fieldwork was aimed at investigating the impacts of coastal ocean acidification on juvenile oysters. (Photo courtesy of Jennie Rheuban, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

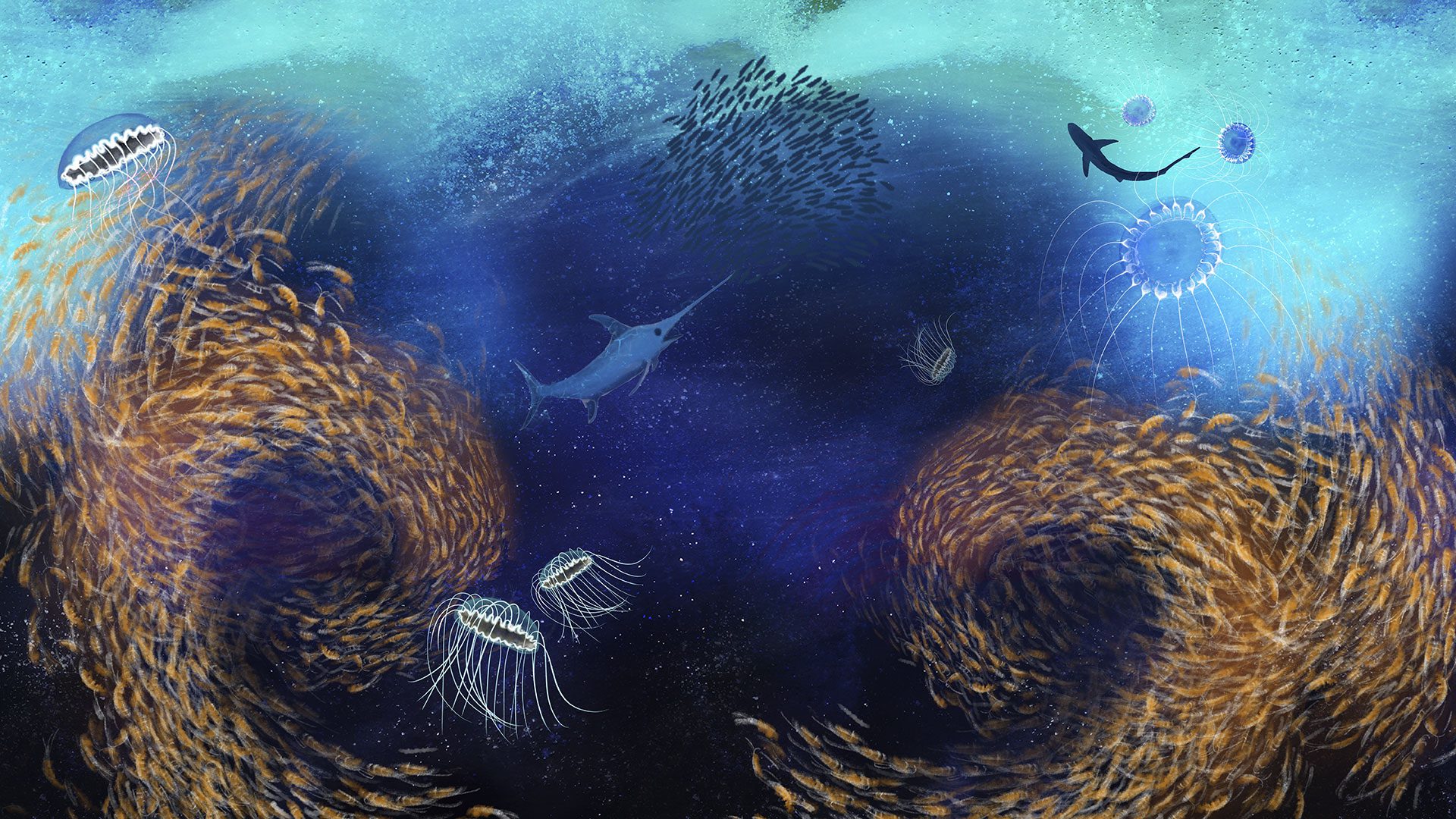

Our oceans have absorbed large amounts of carbon dioxide without changing the pH much. That’s because other ions in the water act as a base and take up those extra hydrogens. Although that’s been good for slowing the rate of acidification, it poses problems for shell-building animals.

“The most common base in sea water is carbonate,” Rheuban explains. Shell-building animals use calcium and carbonate ions from the water as building blocks for their shells. “If there are fewer carbonate ions in seawater because of this increase in hydrogen ions, it becomes more difficult for those animals to produce their shell.”

That’s not all. Animals such as clams and oysters build their shells from the inside, adding new layers as they grow. The outside of the shell is exposed to ocean water; over time those layers can begin dissolve. These shell-building animals must then balance building new shell with losses, and as water becomes more acidic they can struggle to keep up. Rheuban notes that animals in areas with more acidification—often near coastlines—can have thinner shells than those found in areas with a higher pH.

Some people point to animals that don’t seem to be affected by acidification as evidence that it’s no big deal. But some species can handle acidification better than others, Rheuban says. Their susceptibility also varies depending on their developmental stage. All rely on calcium carbonate, which occurs in different forms. Shell-building animals typically use aragonite and calcite. “Aragonite is more easily dissolved than calcite is,” Rheuban says. “Most larval shellfish use aragonite to build their shells before they metamorphose” into the adult form. That means that seemingly healthy adult populations of clams, oysters, or other shell-building animals may not last long-term, because their larvae may not survive long enough to replace them.

“The story is very complicated,” Rheuban says, and scientists are working to tease apart the various pieces of the puzzle. But no matter how you look at it, ocean acidification poses a serious threat to marine life.