This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2024

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2024

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

I am in Cornwall, in the far southwest of England, swimming in Mount Bay with a local group. There are five of us swimming and a guide on a bright yellow paddleboard. We start in the fishing village of Mousehole, where a hillside of stone cottages overlooks a harbor sheltered by two piers. Outside these walls, the bay is known for a thriving fishing industry, a castle once inhabited by monks, and violent winter storms.

We enter the harbor, swimming over a sandy bottom and scores of mooring lines bright with green algae. The water is 16°C (~60°F). It’s cool enough that I’m glad for my wetsuit, but this is the warmest this area gets all year. We are out of the harbor mouth quickly; the bottom changes from sand to black rock. It is so clear underwater that I can see my companions stroking from meters away. It is so still that the first jellyfish I encounter seems fixed in place, its tentacles barely moving.

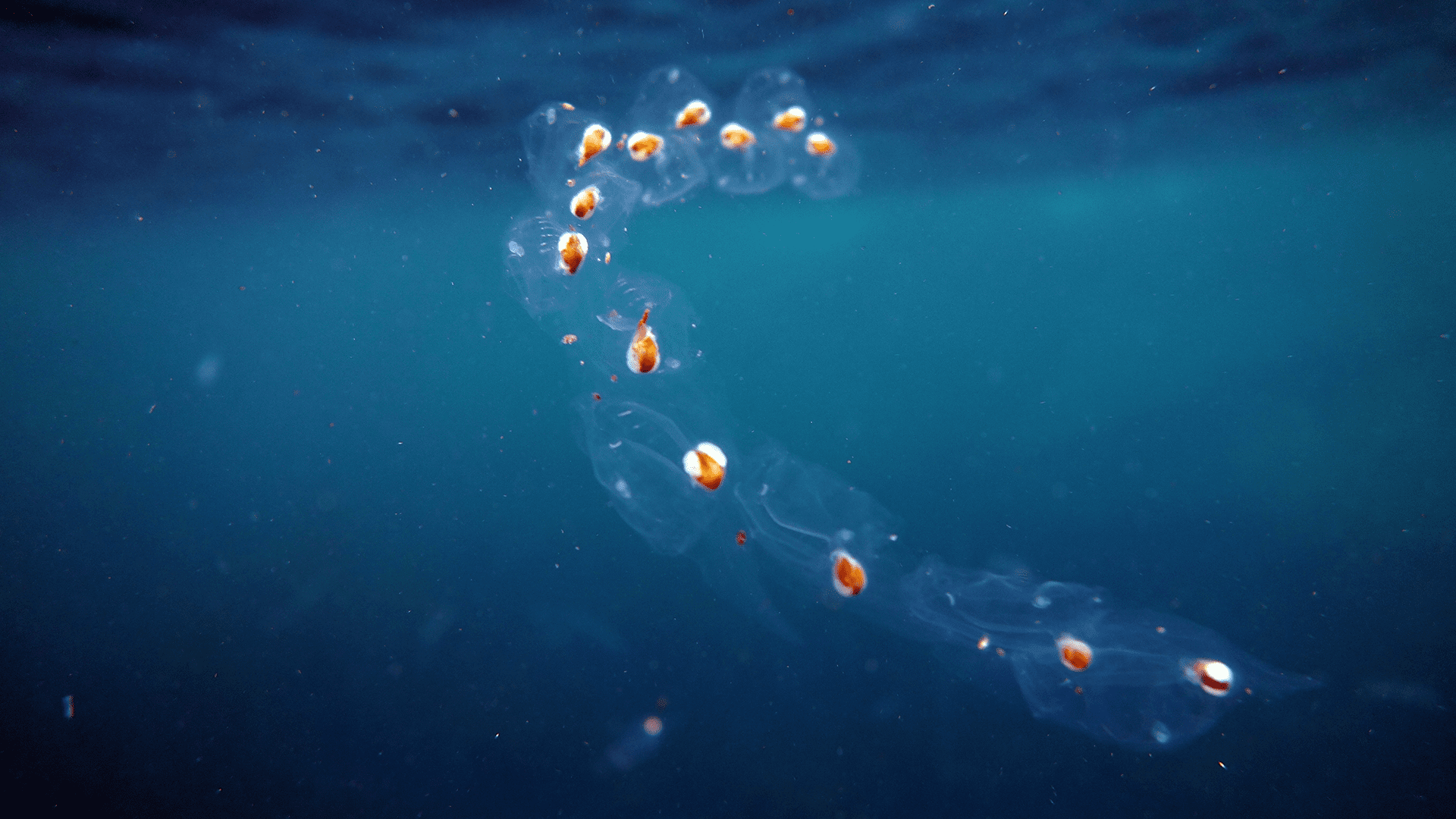

Then, below me, I see something else: a host of gleaming creatures, catching the daylight, shining in relief against the black bottom. These long, translucent chains look like ocean peapods, flecked with orange. There are more than I can count, and they are layered along the bottom in every direction.

I surface to see if anyone else has noticed and so does another swimmer. “What are those things underwater? Do they sting?” she asks the guide.

It takes me a moment to remember what they are called, but I recognize them as creatures that usually live far out at sea. I know they filter the water and poop out carbon, and I am confident that they aren’t going to sting us. They’re salps!

We are swimming through a bloom of the salp species Salpa fusiformis, which washes up on beaches across Cornwall for the next few days, makes UK national news, and then vanishes.

Encountering salps near the coast is rare. Scientists who study them usually board research vessels and venture past the continental shelf to find them. Salps prefer open water and live in every ocean except the Arctic. Some salp species are part of the great company of marine creatures that migrate to the surface each night and return to the half-darkness of the twilight zone—200 meters deep and beyond—when the sun rises. Other species live only in the upper waters.

Another swimmer dives down and brings a chain of salps to the surface. She hands it to me. Each individual Salpa fusiformis is about the size of a walnut, made of a firm, clear, gelatinous substance. They have a brain, a mouth, a stomach, muscles that contract to propel them through the water, and a heart that can beat in two directions. They are part of the phylum Chordata, distantly related to humans, fish, and many other animals found on land and sea.

Their life cycle is brief—a matter of weeks. A single salp buds off of a chain of asexually produced clones that can contain as many as 100 individual salps. Each salp in the chain gestates another, releases it as a solitary creature, and the cycle continues.

Our swim continues around a ragged black rock a few meters long named St. Clement’s Isle. We are told to look out for seals, but there are none here today. Just a few cormorants are fishing. We make our way back toward the harbor, covering about 1,600 meters (nearly a mile).

Salps have been found as deep as 2,000 meters (6561 feet) and tracked swimming up to 500 meters (1640 feet) in a day. But even with these skills, it’s unlikely they reached this coastal area by swimming alone. Wind and currents swept them into shallow water. Abundant plankton and other matter nourished them. And they bloomed into a dazzling starfield, a rare view for swimmers, just below the surface.

This story was written in consultation with WHOI scientist Larry Madin.

Photo by Heather Hamilton © Cornwall Underwater