Mary Sears and the race to solve the ocean in World War II

How her expertise on tides, currents, and swells saved American lives overseas

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

In the predawn hours of Nov. 20, 1943, Higgins boats packed with hundreds of U.S. Marines launched for the island of Tarawa in the central Pacific Ocean.

Tarawa, the site of a landing strip under Japanese control, was a must-have objective in the Allies’ island-hopping Pacific Campaign of World War II. Capturing it, however, would not be easy. Amphibious landings against an entrenched opponent never were, but Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, hoped to minimize casualties at Tarawa with naval and aerial bombardments.

That hope turned to ashes when the landing boats slammed into a coral reef that encircled the island 800 feet (243 meters) from shore. This left the Marines no choice but to abandon their boats and wade to shore through a blizzard of bullets. The Americans managed to capture Tarawa, but at great cost—1,000 American lives lost and 2,000 more wounded, out of an initial landing force of 5,000. These horrific casualties stunned the Navy and shocked the American public.

The military knew about the coral reef encircling Tarawa and that Higgins boats required a minimum draft of 4 feet to cross. But instead of relying on oceanographers, war planners had consulted outdated nautical charts and unreliable foreign sources and surmised that the tide would be at least 5 feet (1.5 meters) on D-day. November 20, 1943, however, was one of two days in the year that a neap tide prevailed with the moon in apogee, conditions that resulted in a lower than expected tide with a narrow range. Rather than reaching 5 feet or even 4, the tide remained at just over 3 feet (.9 meters) for the next 48 hours, sealing the fate of stranded marines who could not find a safe route to shore.

Tarawa exposed a startling but undeniable truth. In advance of large-scale amphibious warfare, the Navy had failed to analyze basic oceanographic features that could be critical when launching plywood landing boats into an angry and unpredictable sea.

“You killed my son at Tarawa,” a mother wrote to Nimitz, just one of many letters that caused him to rethink his strategy.

Nimitz likely didn’t know that while the Tarawa debacle was unfolding, a reserved female scientist working behind the scenes at the Naval Hydrographic Office in Suitland, Maryland, was already collecting data that could help prevent another disaster at sea.

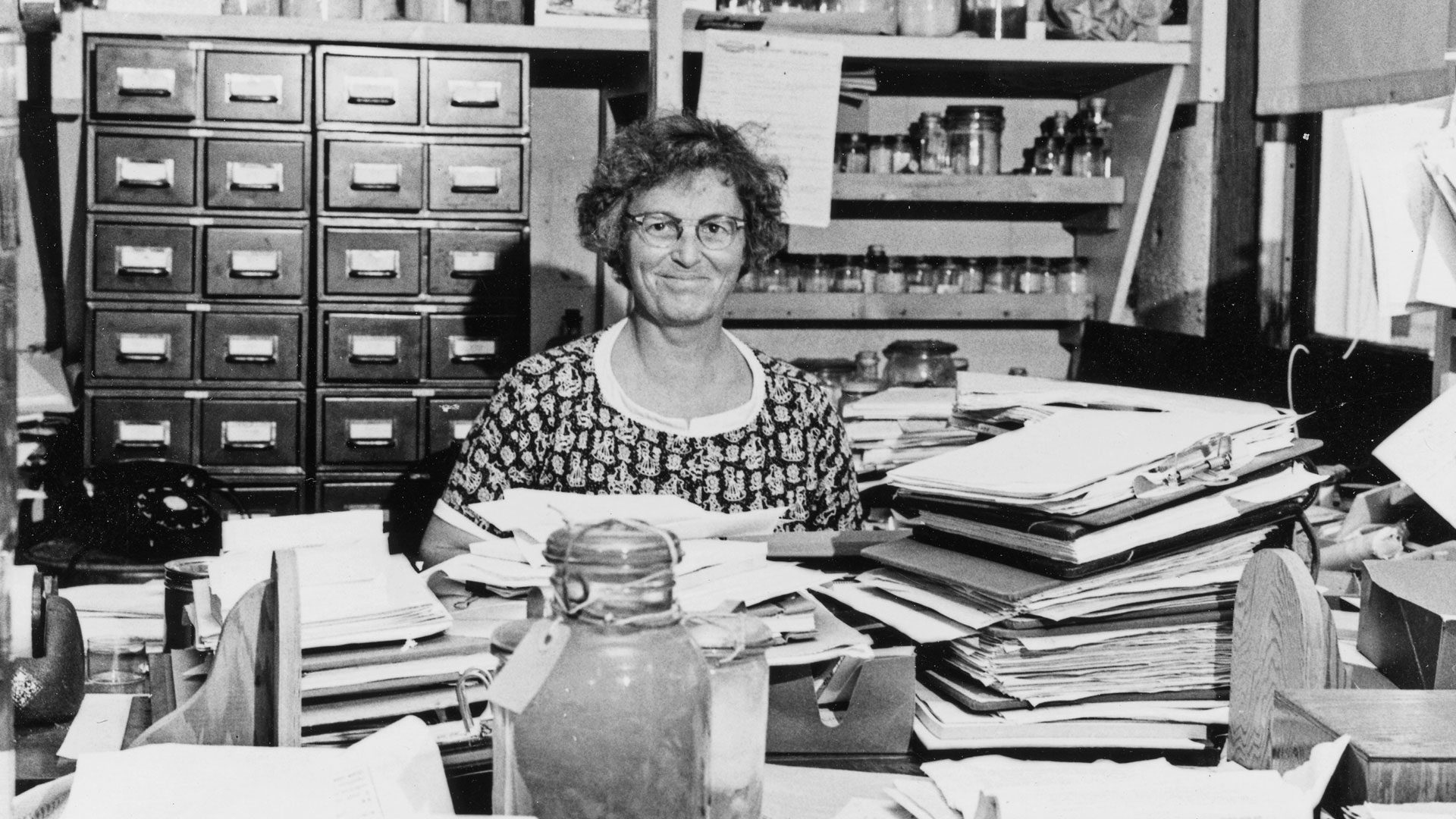

Mary Sears, a native of Wayland, Massachusetts, had attended Radcliffe College, studying with Henry Bryant Bigelow, an internationally known oceanographer and one of the founders of WHOI. Sears had joined Bigelow at WHOI in 1930 when less than 5% of scientists were female. She had become a leading expert on plankton despite never being allowed to board an American research vessel as a female. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Sears was collecting plankton from a fishing trawler off the coast of Peru—her first chance to take her own samples at sea.

When Sears returned to WHOI from Peru, she sought to join the war effort, applying to the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), the women’s naval branch in May 1942. By the time Sears completed basic training, and reported for duty at the Naval Hydrographic Office, the U.S. had been at war for a year and a half. In April 1943, Sears, the first full-time oceanographer of the Navy, attended a meeting of the Joint Chief’s Subcommittee on Oceanography where she discovered that “the Navy went to war without knowing enough about the oceans,” as she later said.

“She had become a leading expert on plankton despite never being allowed to board an American research vessel as a female.”

She demonstrated her research skills in one of her first assignments for the Joint Chiefs. After Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s plane went down in the Pacific, the higher-ups wondered why it had taken 21 days to find the crew despite an intense search. With so many planes being lost at sea, the Navy needed a faster way to locate survivors. Just one month after reporting to duty, Sears submitted her report, The Drift of Objects under the Combined Action of Wind and Current, zeroing in on the easiest and most reliable way to calculate drift, so that life rafts could be found faster.

In 1943, the Joint Chiefs initiated the Joint Army Navy Intelligence Studies (JANIS) to delineate a region’s physical, geographic, and demographic characteristics for combat missions. Sears oversaw the oceanography section, an extensive analysis that included 33 oceanographic topics. Every detail that could affect a military mission had to be accurate. Tides, currents, and waves impacted the timing and route of all landings. Bottom sediment dictated the placement of underwater mines. Bioluminescent algae illuminated the wake of vessels at night, and underwater organisms such as snapping shrimp could interfere with sonar signals.

Sears’ team searched for critical information on Pacific Islands, many of which had been under Japanese control for decades. As such, U.S. survey ships had not been allowed anywhere near them. But the team persisted and located scientific publications in libraries, some published by the Japanese well before World War II. The oceanographers compiled key data and then translated them into terms war planners could understand and apply. They also responded to urgent requests about the ocean for unplanned missions. Sears was asked to perform last-minute tidal estimates for targets so secret that only she had the security clearance to make them.

In the Philippines, Sears used historical wave data and knowledge of expected winds to estimate that the surf would be less than 6 feet (1.8 meters) on the eastern side of Lingayen Gulf at landing. On Jan. 9, 1945, an armada of Allied ships found calm seas off the coast of Luzon with gentle swells and a mild surf as Sears had predicted, making for one of the smoothest amphibious landings of the war.

At Okinawa, the last major amphibious landing of the war, Sears noted the possibility of high waves on the western coast in her preliminary report, but the preferred beaches were in that same area. War planners consulted her again, and after reviewing more recent data for the exact date, Sears concluded that the waves would likely be unremarkable at landing. At dawn on April 1, 1945, the largest convoy of marines launched in the Pacific during World War II sped safely to shore in calm seas and landed 50,000 troops by early afternoon.

The first Naval Oceanographic Unit had succeeded in churning out voluminous oceanographic intelligence for combat missions and preparing manuals and advisories that helped win the war.

“Please thank Mary Sears,” a naval officer wrote to Admiral George Bryan, her supervisor, during the war. Admiral Nimitz appreciated Sears also, issuing a commendation highlighting her contribution of “valuable information for use in combat operations.” The Navy acknowledged Sears again in 1999, two years after her death, by naming an oceanographic survey ship after her, the first woman to be so honored.

Today, the USNS Mary Sears sails around the world, staffed by oceanographers, male and female alike, continuing the work of the woman who dedicated herself to their same mission during World War II—to defend the United States and keep its armed forces safe at sea.