Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

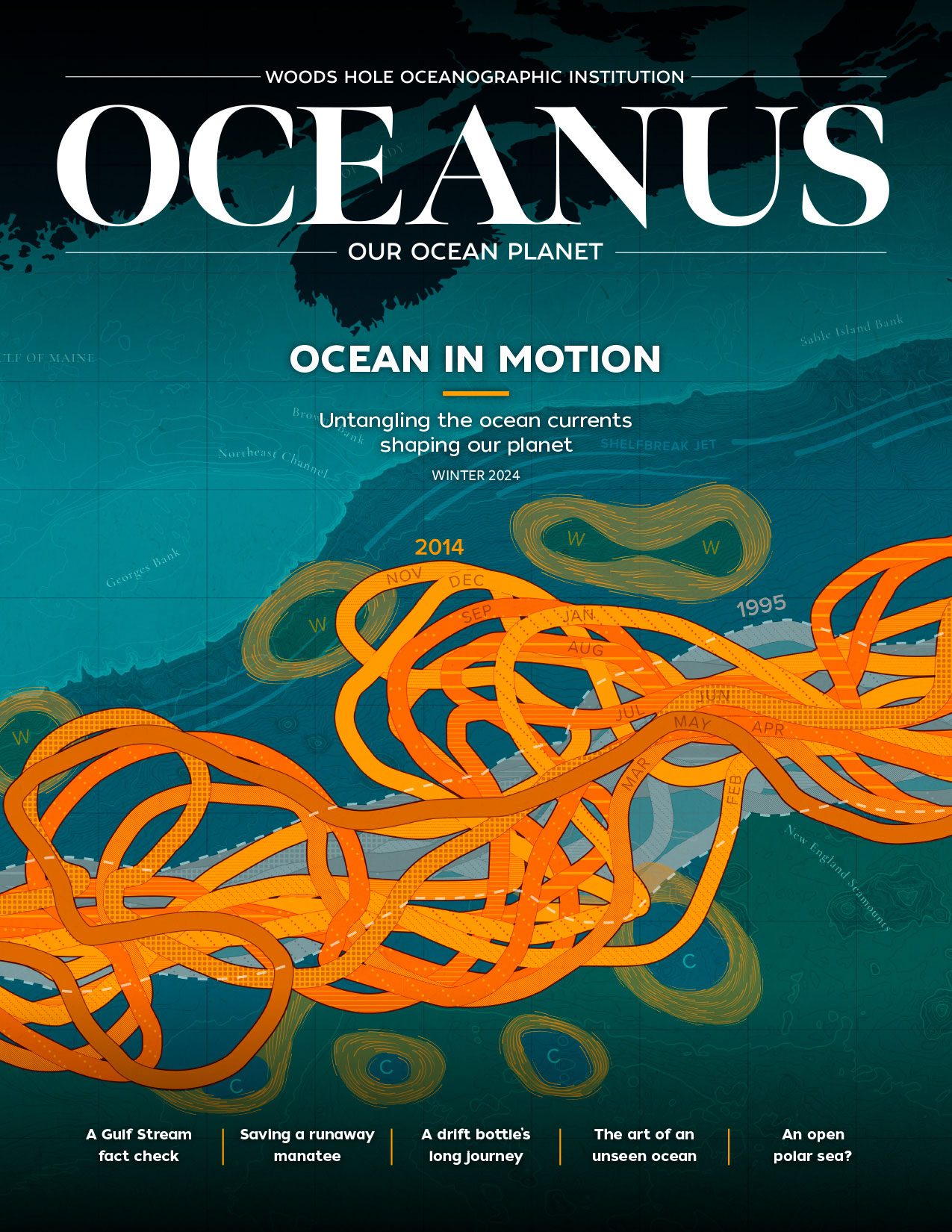

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2024

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2024

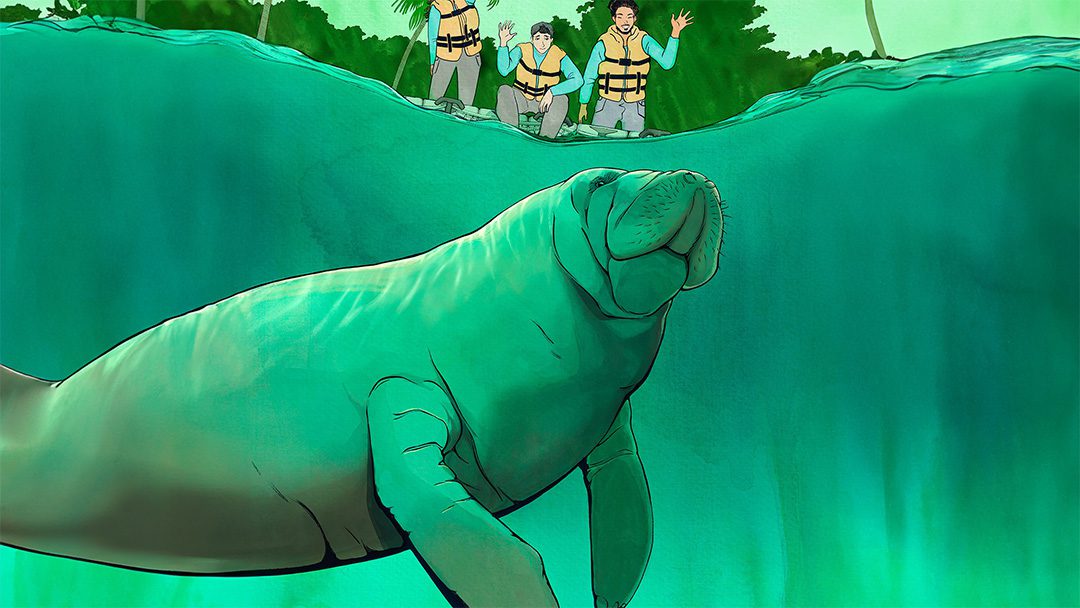

On July 6, 2022, along the turbulent coast of Icapuí, Brazil, Tico, an eight-year-old West Indian manatee paced placidly in his net pen for the last time. His caretakers, a marine mammal rescue group called Aquasis, had long awaited this day. After nearly a decade of rehabilitation, Tico was finally being released back into the wild for the first time since his rescue as a newborn.

Aquasis had a lot riding on the manatee’s success. No more than a thousand members of Tico’s subspecies (also known as the Antillean manatee) remained in the wild south of the Amazon River mouth. Over the last century, dwindling mangrove habitat, collisions with boats, and entanglements in fishing gear had bottlenecked the population. Helping the species recover has since been a herculean task. Newly rescued manatees require a lot of time and attention. Calves must be weaned on lactose-free formula at least five times a day, while others get routine blood draws and medical exams. Individuals that show signs of independence graduate from aquarium tanks to coastal pens. There, they can acclimatize to their natural environment—where Tico was now.

Typically, it takes five years before a manatee is ready for release. Tico, who was skittish around humans, took nearly eight—“not an ideal amount of time,” according to Aquasis senior veterinarian Vitor Luz Carvalho.

Having shown a clean bill of health and that he could find food independently, Tico didn’t need to be held any longer. It was now or never for the manatee.

Back in Icapuí, Luz Carvalho and his team lowered the net gateway, and Tico slunk into the sea, his gray, potato-like frame quickly vanishing beneath the surface. A GPS tracker buoyed above him, lashed to a belt strapped around his fluke, so that Aquasis could track his whereabouts.

Of all the directions a manatee like Tico might choose, no one could have guessed where he would go next. Just 12 days after his release, Tico veered east—toward the open sea.

While typical West Indian manatees prefer to live in shallow water inlets no deeper than 10 meters (30 feet), Tico had strayed over the continental shelf break, where average depths reach more than 3,000 meters (10,000 feet). Something wasn’t right.

“He started moving west at a fast speed,” says Aquasis monitoring coordinator Camila Carvalho de Carvalho. “Then he started moving away from the coast.”

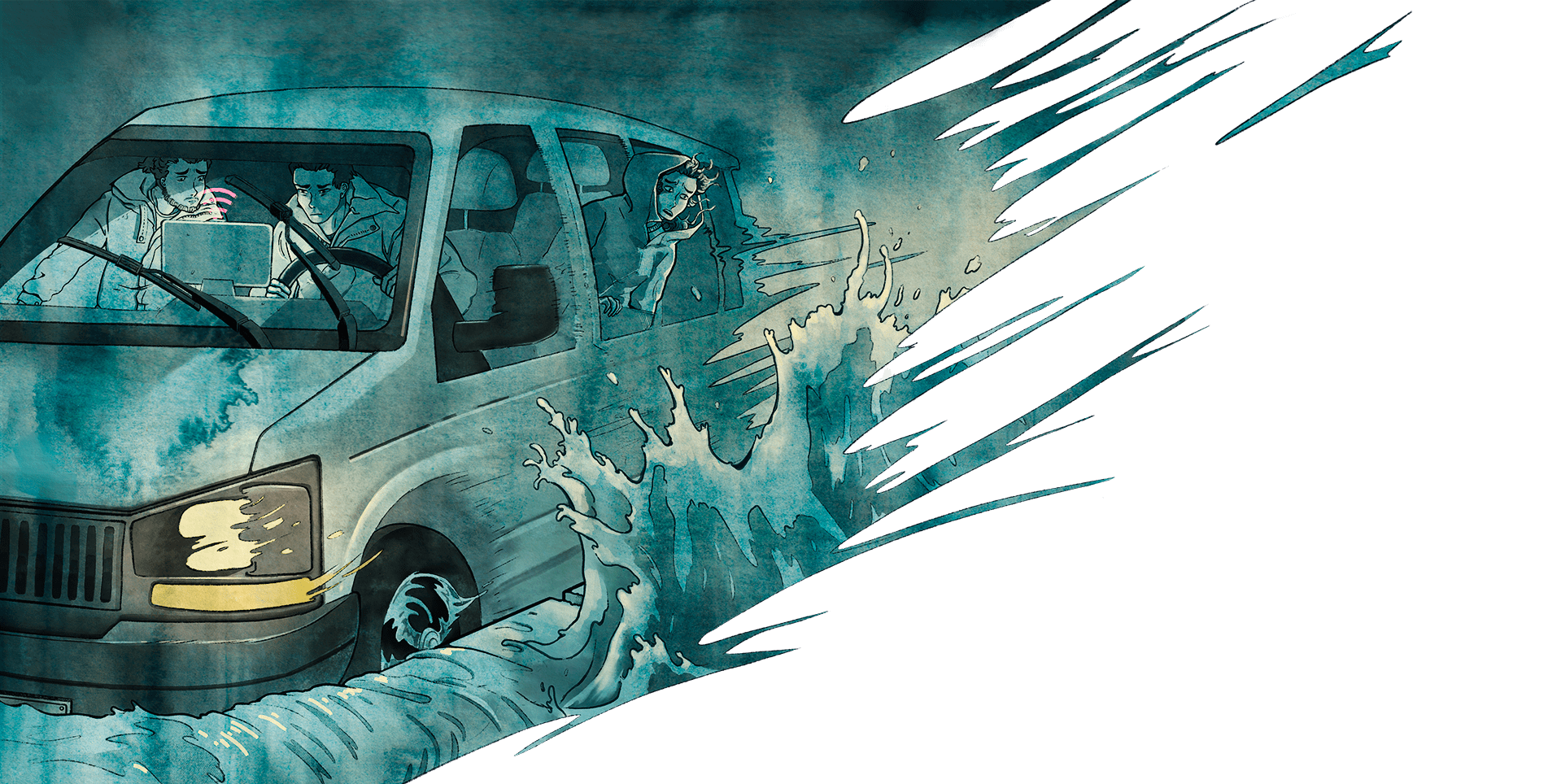

In short order, the distances between Tico’s coordinates began to widen on Carvalho’s computer screen. He was picking up speed—much faster than the languid pace that manatees typically move at. It became clear: Tico was caught in the crosshairs of a powerful current. His short-lived freedom had quickly turned into a rescue operation.

The race was on to bring Tico home.

In the crosshairs

To the uninitiated, the manatee’s movement appeared to be nothing more than an impressive long-distance swim. But WHOI physical oceanographer Iury Simoes-Sousa knew better.

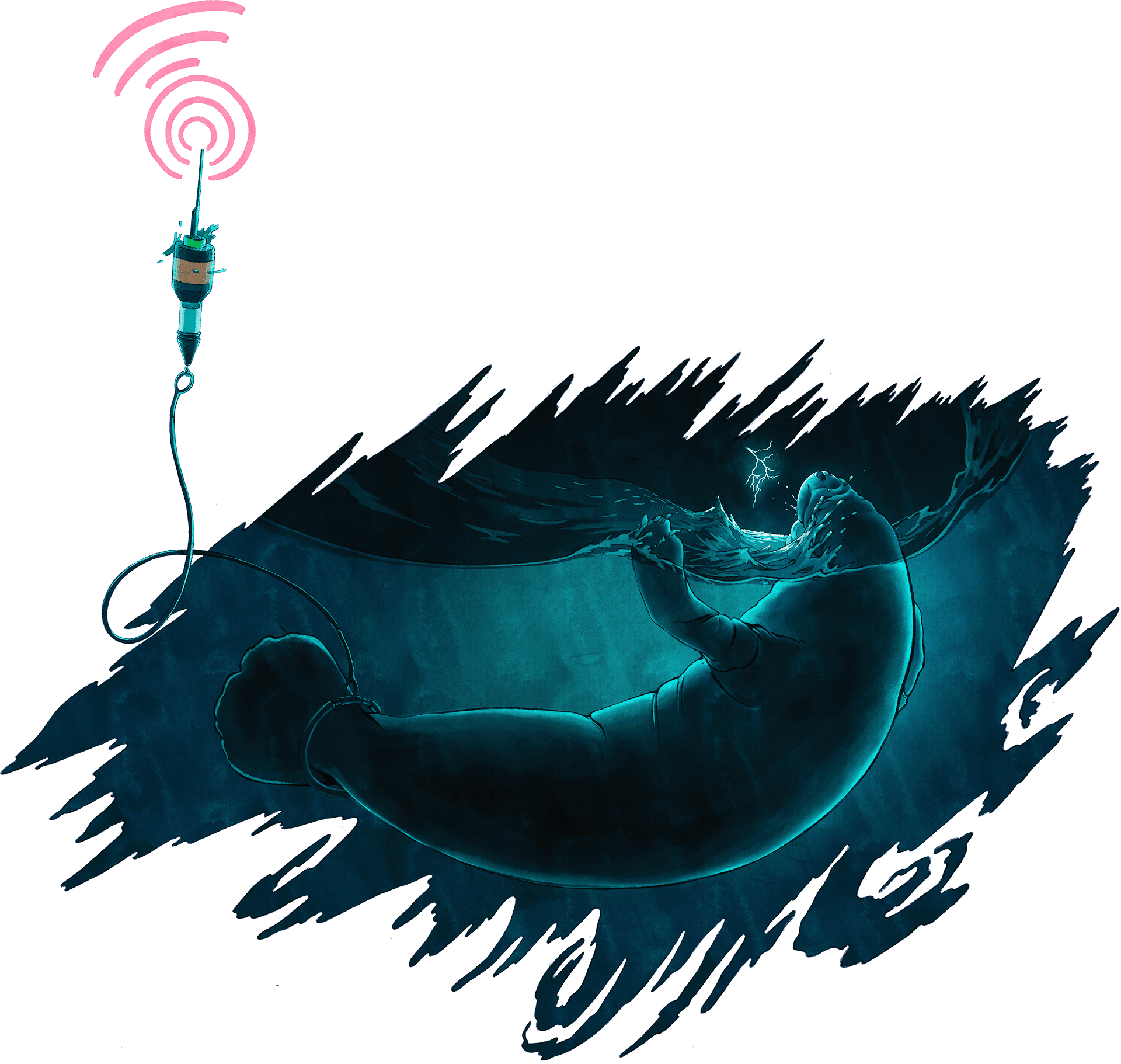

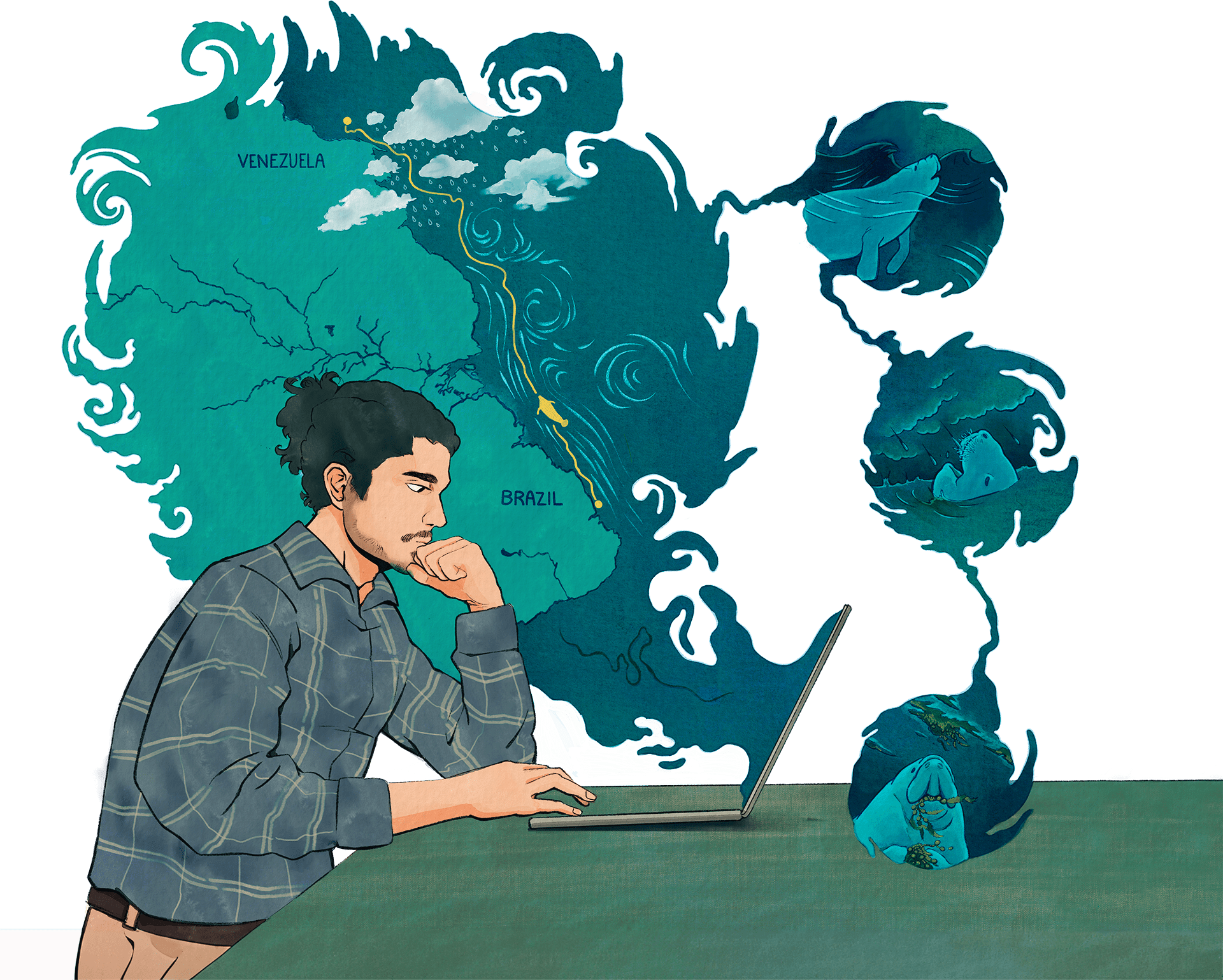

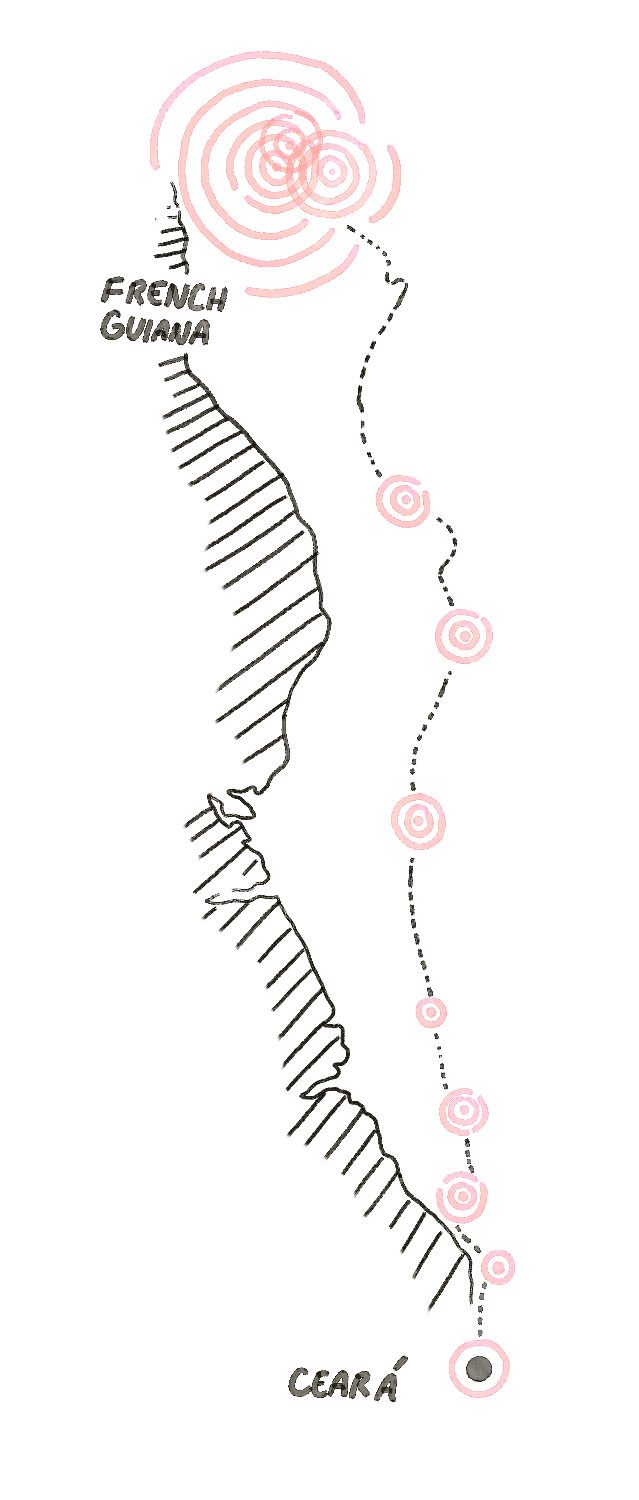

“This was not the pattern of a manatee swimming by itself,” says Sousa, who was later asked by Aquasis to analyze Tico’s telemetry data. “When Aquasis showed me the trajectory, it was clear that this manatee was carried by the North Brazil Current.”

A native Brazilian, Sousa has studied the currents around the country’s coastline his entire career. The North Brazil Current is perhaps Brazil’s most prominent oceanographic feature, known for bringing warm equatorial water north before connecting to the Gulf Stream. At nearly 200 miles (322 kilometers) wide, it would be nearly inescapable for Tico.

The manatee’s trip couldn’t have been pleasant. Hindcast models—simulations that show past weather and sea-state conditions—as well as satellite data told Sousa the harrowing story of Tico’s time at sea. The manatee’s path intersected several violent storms that likely tossed him around relentlessly. Nearby counter currents pushed against the North Brazil Current, causing the animal to zig tantalizingly close to land, only to zag back out to sea.

“I didn’t have any experience with manatees before, but I had some experience with the currents in the region,” says Sousa. “I was really sad for Tico. I’m sure it was a tiresome journey.”

Understanding the current’s role in Tico’s journey would later become crucial in building the case to bring him home. The closer the animal got to international waters, the more likely it was that Aquasis would need approval from the Brazilian government to broker his return. Like the U.S., Brazil is a signatory of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). As such, the country would not sanction the relocation of any animal that had traveled a route of its own volition. Luz Carvalho and Carvalho de Carvalho knew Tico didn’t choose this path, but they would need Sousa’s analysis to prove it.

From Tobago with Love

By the time Aquasis had reached the city of Belém, they had driven 900 miles (1,448 kilometers). Their next destination, Macapá, was the northernmost town in Brazil, reachable only by plane. It was their last hope to catch Tico.

But before they could book flights, Luz Carvalho made a sobering observation.

“At a certain point, when Tico got past French Guiana, we started seeing a lot of the coordinates [bunch up] close to each other,” he says. At that point, “we thought it was just a carcass that was floating at the surface.”

In 90 days, the current had carried Tico a mind-boggling 2,500 miles (4,023 kilometers). Without easy access to food or water, it was unlikely he had survived the journey thus far, thought Luz Carvalho. By entering international waters, the manatee had made an already difficult rescue much more complicated—requiring a slew of visas, security clearances, and import licenses. Continuing would mean exhausting resources Aquasis no longer had to rescue a corpse. Luz Carvalho, who had rescued Tico as a newborn, had a tough call to make. The rescue mission, it seemed, was over. Little did they know Tico was not finished yet.

Twenty days later, his tracker began to ping from the Caribbean island of Tobago. After checking in with nearby scientific peers, Carvalho de Carvalho received an unexpected email, this time from two fishermen:

“Looks like the manatee is alive,” it read.

Soon after, a video came in on the texting forum WhatsApp showing the gray mass of a manatee floating by, the antenna of a tracker bobbing above him in the water. Against all odds, Tico had survived.

“Some people cried,” says Luz Carvalho. “We thought Tico was a more fragile animal, so it was really surprising when he got past it all and survived.”

Sluggish and likely dehydrated, Tico kept moving. In a flash, Luz Carvalho called everyone he knew in the area. By the time the manatee reached the Margaritas Islands in Venezuela, local coast guard units were awaiting his arrival. Together, with a motley crew of NGOs and scientists, they corralled the animal and transported him to a holding tank at a local aquarium—Waterland Mundo Marino.

Homecoming

Aquasis leaned heavily on Sousa’s expertise in the months following Tico’s capture.

By the winter of 2023, Sousa ran dozens of computer simulations, overlaying playback of Tico’s journey with atmospheric and ocean data. Everything from the manatee’s breakneck speed to his meanders aligned perfectly with the movement of the North Brazil Current. Sousa’s analysis even revealed how the manatee survived so long at sea. Satellite data revealed several passing rainstorms had showered Tico with fresh drinking water at various points during his journey. It was likely the manatee slurped it up to survive.

"quote-text">"I had the perspective that I was bringing something to Aquasis and Tico, but with time I’ve realized how much I got from them."

—WHOI physical oceanographer Iury Simoes-Sousa

“We still don’t know exactly what Tico’s behavior was like,” says Sousa. “But I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that this manatee crossed some spots of freshwater that could be drinkable.”

Sousa packaged the data neatly into a report for the Brazil’s environmental ministry. By March 2024, with the added context of oceanographic data, the agency agreed to approve an animal import license so that Aquasis could retrieve Tico.

“It was through Iury’s analysis of the data from our equipment that we were able to prove Tico was being dragged by a current and wasn’t moving naturally,” says Luz Carvalho. It helped, he added, “totalmente.”

The manatee’s journey has since provoked a thoughtful debate over the optimal timing to reintroduce Antillean manatees back into the wild.

“In Brazil, [releasing marine mammal species] is traditionally done by animal specialists. Now we really see the need for oceanographic experts to complement what we do,” notes Luz Carvalho. “Iury has helped us evaluate the influence of currents on animal displacements, not only with Tico, but with other animals too.”

The experience has been just as eye-opening for Sousa, who says Tico has given his work renewed purpose. Today, Sousa is working with Aquasis to identify more favorable oceanographic conditions for animal release—months where freshwater is more available, and wind and currents more forgiving.

Aquasis has since visited Tico at Waterland Mundo Marino to assess his health. Today, they’re organizing transportation to fly him home. It’s a heartwarming victory for Sousa, who says he’s grown attached to the manatee.

“This work was really important for me,” says Sousa. “In the beginning, I had the perspective that I was bringing something to Aquasis and Tico, but with time I’ve realized how much I got from them.”