This article printed in Oceanus Spring 2021

This article printed in Oceanus Spring 2021

Estimated reading time: 18 minutes

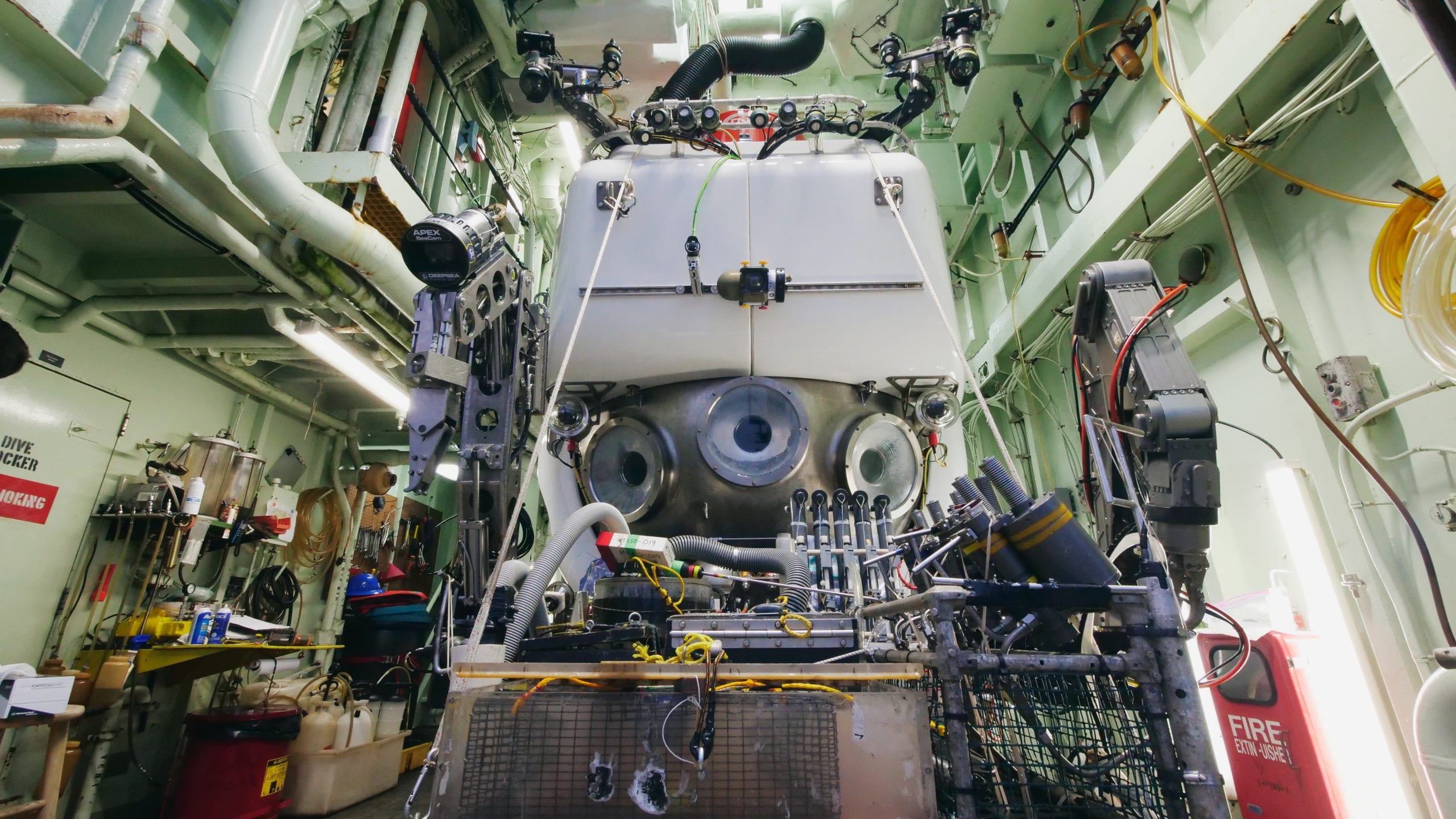

Aboard the research ship Atlantis, the human-occupied vehicle Alvin perches neatly inside a small two-story hangar, where it's draped with ventilation tubes and electrical cables. The streamlined white hull of the sub, which has lately been going through a major overhaul to extend its reach to greater depths, reflects the lights of the deck beyond. Its two robotic arms fold neatly at its sides, framing portholes carved into a gleaming new titanium crew sphere. It looks like science fiction come to life: a small but formidable spacecraft poised to travel to another world.

IN REALITY, THAT'S NOT FAR FROM THE TRUTH. SEAWATER COVER MORE THAN 71% OF EARTH'S SURFACE, leaving much of the globe unknown and mysterious to humans. Exploring its secrets is a bit like studying the workings of a distant planet.

"The ocean is so enormous, so vast, that it's nearly impossible to have a thorough understanding of any one part of it unless you're actually there," says Adam Soule, a submarine vulcanologist and former chief scientist for deep submergence at WHOI. "There's an aspect of exploration and discovery that is inherent in marine research."

In their constant search for understanding, oceanographers from WHOI and elsewhere must go to extremes. Some of those scientists board Alvin multiple times every year, diving to some of the deepest and most mysterious areas of the seafloor. Some peer through the eyes of complex robotic vehicles that can travel where humans can't go. Others travel to the distant edges of the ocean's reach, trekking across frozen polar landscapes to collect ice cores that reveal what the sea looked like thousands of years ago.

“The ocean is so enormous, so vast, that it's nearly impossible to have a thorough understanding of any one part of it unless you're actually there.”

—Adam Soule, submarine vulcanologist and former chief scientist for deep submergence at WHOI

No matter what aspect of the oceans these scientists study, their work can be a massive undertaking. From the deepest marine trench to the tallest landlocked mountain, the sea's influence touches nearly every corner of the globe: It provides food for billions of humans, supplies life-giving oxygen to the atmosphere, and directly affects climate from the deserts of Arizona to the icy coasts and frozen interior of Antarctica. Unraveling the mysteries of a realm this large means entering some of the most remote and dangerous places on the planet. But by going to these great lengths, oceanographers are gaining insights that may answer fundamental questions about life on Earth-and possibly even life beyond.

Submersible Alvin is prepped in the high bay on R/V Atlantis before dive operations along a segment of a deep-sea mountain range known as the East Pacific Rise, off the coast of Costa Rica. (Photo by Ken Kostel, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The poles

The first thing that hits you when you sail into Antarctica's Palmer Station is the smell. After five days at sea in some of the roughest waters on Earth, new arrivals are greeted by a whiff of guano-excrement from the massive penguin colonies that inhabit the peninsula. But the view makes up for it, says WHOI marine geochemist Dan Lowenstein.

"You sail between these sheer walls of rock and snow in the Neumayer Channel, which is the navigational passage along the peninsula, and when you come around one last island, you see this incredibly remote station," he says. "It's just a handful of buildings perched on a tiny bit of rock at the bottom of a huge glacier, next to a harbor bordered by 300-foot cliffs of ice."

Lowenstein arrived at Palmer in December, 2020 and plans to remain there for at least six months. It's a position that requires a certain level of comfort in extreme isolation. Although the population of McMurdo Station, the major U.S. logistics hub on the continent, peaks at 1,300 during the Antarctic summer, the peak at Palmer is only about 45 people. During the Covid-19 pandemic, it's running with an even smaller crew: Lowenstein is one of just 24 scientists and staff currently on hand.

The global public health crisis not only reduced the number of people allowed at Palmer this year. It also hampered travel to the station. Under normal circumstances, the trip takes about a week. This year, Lowenstein spent more than a month in transit, thanks to multiday quarantine stops in Massachusetts, San Francisco, and Chile.

It may be tiny and hard to reach, but Palmer enjoys an outsized importance in the world of oceanography and climate. It's home to a Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) network of more than 30 sites across the globe that have been recording continuous environmental data and samples over the past few decades. At Palmer, the LTER focuses on life that exists in and around nearby sea ice.

A waddle of Gentoo penguins hop around the rocks of the West Antarctic peninsula, where WHOI marine geochemist Dan Lowenstein is currently stationed to study the changing metabolism of the region's microbial communities (Dan Lowenstein, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

"There's no place like it," says WHOI geochemist Ben Van Mooy. "Since going online in 1990, Palmer has provided detailed information about a vast suite of chemical, biological, and physical ocean parameters in the waters that surround it. It's an incredibly valuable record that doesn't exist anywhere else."

Van Mooy has been to Palmer twice to gather samples of the sea ice that surrounds the station. This year, he sent Lowenstein in his place. Every chunk he collected can reveal volumes of information. Since it lies at the interface of the atmosphere and the ocean, Van Mooy says, sea ice is deeply affected by changes in both environments.

"As the atmospheric climate changes, ocean circulation and other marine elements change, and those things are all reflected via changes in the sea ice. It's a really sensitive indicator of both atmospheric and oceanographic processes," Van Mooy adds.

Van Mooy is also interested in how these same processes affect tiny plantlike microbes called phytoplankton. These minuscule organisms form the base of the Antarctic marine food web: They're eaten by animals like krill and shrimp, which in turn provide food for whales, fish, penguins, and other large organisms. Like plants on land, they also produce huge amounts of oxygen for the planet. Yet precisely how they're affected by changing climate is unclear.

"We take a lot of precautions, but the consequences of something going wrong are pretty severe-so it forces you to look inside yourself and see how much you truly love what you're doing."

—Ben Van Mooy, WHOI geochemist

Whatever happens to phytoplankton has a ripple effect across the entire ecosystem of the Antarctic peninsula, Van Mooy says. That means the fate of sea ice at the extreme ends of the world is inextricably connected with the fate of animals like krill, penguins, seabirds, whales, and fish-but to understand this complex ecosystem, Van Mooy first has to venture out into the coastal ice pack to collect samples and data. It's a dangerous undertaking.

"The thing people forget about Antarctica is that it's essentially abandoned," he says. "You can be a quarter mile away from Palmer Station, but once it's out of sight, there's zero indication of humans: No people, no ships, no jets in the sky. Nothing. It's just you and one or two other people working on a small boat in frigid and tumultuous Antarctic water. We take a lot of precautions, but the consequences of something going wrong are pretty severe-so it forces you to look inside yourself and see how much you truly love what you're doing."

Glaciologists Sarah Das and Kristin Poinar carrying a crate off the helicopter. (Photo by Chris Linder, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

LEARNING FROM ANCIENT ICE

Studying the ocean's impact on global climate doesn't stop at the coast. Deep in the interiors of Antarctica and Greenland, a record of how the oceans behaved thousands of years in the past is preserved deep within layers of buried ice.

A research team led by Das hikes alongside an icy crevasse in Greenland to study changes in meltwater distribution across the glacier as the climate warms (Sarah Das, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution).

Sarah Das, a WHOI glaciologist who studies climate history, spends her days traveling to some of the most lonely spots on the globe. She and her team have helicoptered into remote mountain glaciers in Greenland, and have flown on small aircraft into isolated corners of Antarctica to gather ice core samples.

"I'm by definition interested in studying places that humans haven't been to before. You can only fi nd good climate archives in totally pristine, untouched ice-so wherever I go in the field, I'm usually the first person ever to set foot there," she says.

In isolated regions, polar ice sheets can stay untouched for hundreds of thousands of years, providing an incredibly long record of past climate, she notes. Unlike sea ice, which forms annually from seawater itself, glacial ice sheets are created by progressive layers of snow. As each storm blows through, new snowfall buries prior years' snow layers deeper and deeper, preserving dust and tiny air bubbles in the process. "You essentially get all these bits of the past atmosphere trapped within ice layers. As climate scientists, we collect these clues and can unravel mysteries such as how much snow fell in the past, how many warm events there were, and what atmospheric greenhouse gas levels were during specific times in history. It feels sort of like having access to a time machine," says Das.

"You can only find good climate archives in totally pristine, untouched ice-so wherever I go in the field, I'm usually the first person ever to set foot there."

— Sarah Das, WHOI glaciologist

It turns out the ice layers also trap compounds that can help tease out natural processes happening in the oceans during the same era, she adds. "For example, in Greenland we recently showed how we can use organic compounds in ice to reconstruct the productivity of marine phytoplankton in the past. Th at extends our knowledge of how climate change impacts the base of the marine food web."

Collecting those samples is no small feat. Working in Greenland, Das spends days hauling gear on and off craggy coastal mountaintops to get to undisturbed patches of ice. In those cases, she says, there's at least a few small communities along the coast that she can use as a base of operation-but when she's working in Antarctica, her team has had to set up camp on the ice sheet for weeks at a time.

"You get on a military transport plane in New Zealand where it's summer, and several hours later, you set down in Antarctica and walk out into blinding snow. It's like flying to another planet," she says. "It doesn't even feel connected to Earth."

ROV Jason slowly touches down to take pictures with the "MISO" camera along Havre volcano, northeast of New Zealand. (Photo courtesy of Dan Fornari, Chief scientists Adam Soule and Rebecca Carey, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The deep

When it comes to extreme distances, traveling to the Antarctic ice sheet ranks high on the list. Traveling to the deep ocean, however, is an entirely different-and arguably more dangerous-challenge. It's an otherworldly place, with crushing pressures, bizarre life, and a trove of hidden scientific secrets waiting to be revealed. To study its inner workings, ocean scientists must descend to its furthest reaches, either via robotic vehicles or by braving its depths in person within the cramped quarters of a research submarine. Once there, it becomes possible to find clues to how the very early Earth may have behaved.

The volcanic rock and fluids that well up from below the ocean floor in some regions offer scientists a clear look at geologic processes that have shaped life on our planet. In areas called "spreading centers"-mountainous chains that extend for thousands of miles across the ocean floor-magma from the Earth's mantle rises up from below the seafloor, pushes entire continental plates apart, and introduces key nutrients that enable life to thrive. Studying midocean spreading centers offers a window into that deep world, provided scientists can get there in the first place.

"We've studied so little of the midocean ridge and other spreading centers-but as we keep returning to them, we keep finding new things," says Jeff Seewald, a marine geochemist at WHOI and interim Chief Scientist of the National Deep Submergence Facility.

In his current post, Seewald spends his days not only studying fluids that well up from the seafloor but also working to make it possible for other scientists to reach those extreme depths.

Since the HOV Alvin, WHOI's famed research submersible, was overhauled in 2013, it has completed more than 400 dives, bringing at least 350 researchers on their first trip to the ocean floor. "That's about the same as the number of U.S. astronauts that have left low Earth orbit since the space program started 60 years ago. In bringing humans to extreme places, the Alvin program punches well above its weight," adds Adam Soule.

At the moment, those scientists are able to go as deep as 4,500 meters (14,800 feet), but the sub's latest overhaul will let it travel even farther-to 6,500 meters (21,325 feet). Th is new range will bring scientists to areas of the seafloor that were previously unreachable, enabling exiting new discoveries in the process.

"Beyond 6,500 meters, there's a whole region of the ocean that's been understudied. We just don't know what's down there," says Seewald.

Deep Life

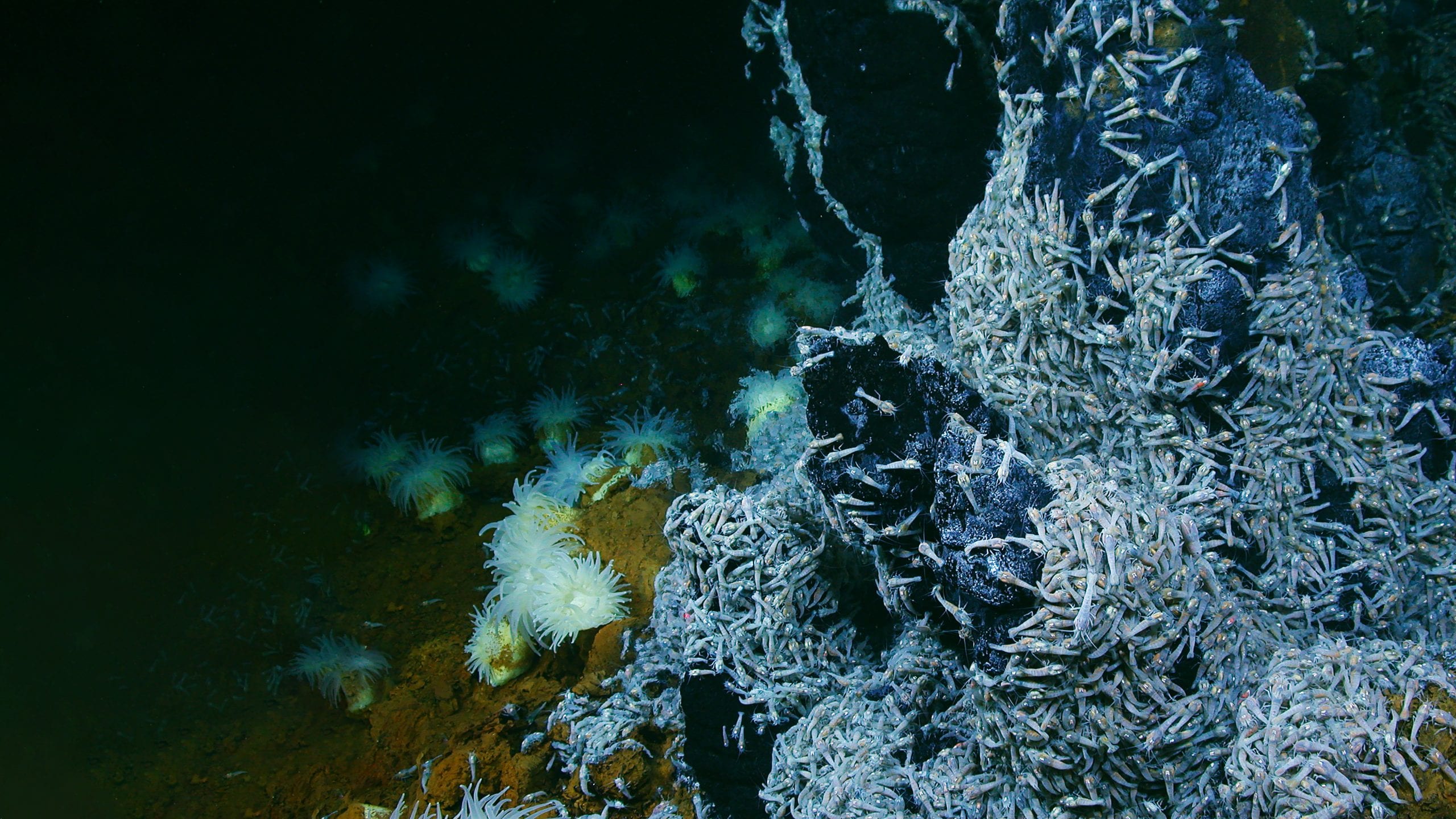

Many of the latest Alvin dives have been to hydrothermal vent sites-hot geysers found mainly in midocean spreading zones. Nearly 2,500 meters (8,200 feet) below the ocean's surface, in an otherwise barren landscape, the chemicals released by each vent support a strange array of life. Giant tube worms, blind shrimp, huge clams, and other species thrive around the vent's flanks, fed by microbes that create chemical energy from the venting fluids themselves.

For many WHOI scientists, however, the extraordinary animals at vent sites aren't the main attraction. Rather, it's what exists below them. Vent sites provide a unique portal to the interior of the planet, as the ultrahot fluids that emerge from them contain minerals that are shaped by intense heat and pressure beneath the crust. They also provide clues to even more unusual life-forms-researchers are beginning to fi nd evidence of a hugely diverse array of microbial life both on and underneath the seafloor, where those liquids react with rock.

To WHOI marine microbiologist Julie Huber, the idea that life exists deep within the crust make perfect sense. Most life-forms on Earth have been here for only a short chunk of the planet's 4.5 billion-year history. For much of that time, microbes ran the show. "Microbes have likely existed for billions of years in these crustal environments of the deep ocean-so studying them can improve our understanding of the tree of life on our planet," she says.

To probe those mysteries, Huber not only samples fluid directly from vent sites but also has supervised even more dramatic eff orts: drilling operations that dig into the seafloor from aboard a specialized ship, tapping hundreds of feet straight down from the deepocean floor to reach fluids percolating through the mud and rock beneath.

"Studying the sub-seafloor isn't glamorous, and it's really hard to reach," she says. But it can be well worth the intense eff orts. Once a drill hole has been dug, scientists can cap it and sample fluids from below the seafloor on a regular basis, revealing a world that's largely inaccessible through other methods.

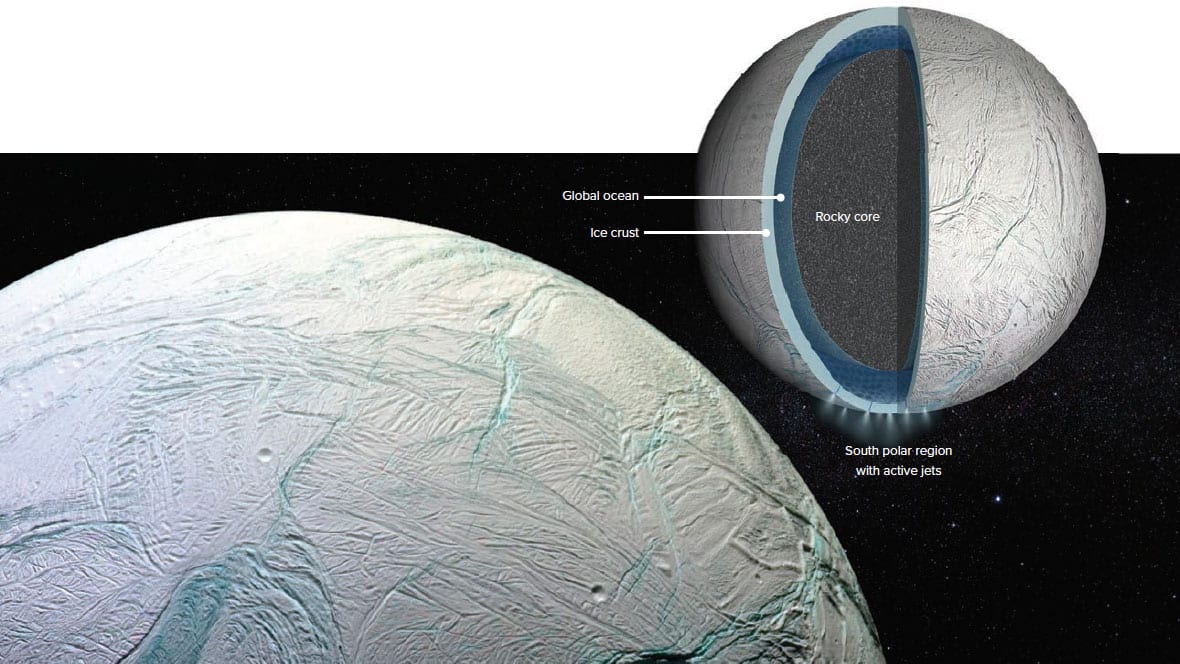

To search for life, spacecraft will need to be able to penetrate the icy crust of ocean worlds like Enceladus, where vehicles similar to WHOI's Nereid Under Ice can be deployed to survey the water below. (Illustration courtesy of © NASA Jet Propulsion Lab)

Ocean worlds

Whether it's traveling to the distant poles, the deepest vent sites, or below the ocean floor itself, the lengths to which oceanographers go to study Earth's processes are helping answer questions not only about our own planet, but about other watery worlds as well.

Enceladus, a tiny moon of Saturn, is only about 300 miles (500 kilometers) wide yet shares an eerie similarity to some of the regions on Earth that WHOI oceanographers are currently examining. Planetary scientists have recently shown that its surface is made up of slabs of solid water ice sitting atop a liquid saltwater ocean, similar to what you'd fi nd at our own planet's poles.

Mysterious geysers on its surface regularly eject material from Enceladus into space-and after NASA's Cassini spacecraft maneuvered through those plumes in 2015, the data it sent back to Earth raised more than a few eyebrows. Not only did the plumes contain ice, water, and salt, but they also contained chemicals like silica, methane, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen, a suite of compounds that is all too familiar to oceanographers like Chris German.

"The only place we know where little silica nanoparticles like these form on Earth today is in midtemperature hydrothermal vents" where the escaping fluid is roughly 100 degrees Celsius (212 degrees Fahrenheit), says German, a marine geochemist at WHOI. "It seems like compelling evidence that there could be submarine vents active today on the seafloor of Enceladus."

In other words, by studying the ocean's extremes on Earth, WHOI researchers are setting the stage to examine a world disconnected from ours by more than 746 million miles (1.2 billion kilometers), German adds.

The vent sites on Enceladus could share an exciting similarity with newly studied sites on our own planet.

WHOI senior scientist Chris German has worked with engineers to test Nereid in the Arctic for that very purpose. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

An unusual cluster of deep vents called the Von Damm field, which German helped identify in the Caribbean Sea less than a decade ago, turns out to have a unique chemistry: It emerges from rare ultramafic rock, which is found in the Earth's mantle today. In the presence of heat and crushing pressures below the ocean floor, those rocks react with seawater to create something truly mind-boggling: organic compounds, the building blocks of life.

"Based on our measurements, we could make the case definitively that organic compounds are getting synthesized spontaneously, without any input from an existing life-form. Just rocks and water, as a geologic process, are generating the chemical building blocks that are essential to creating life," German says.

The same may be happening on Enceladus.

German and his colleagues are hoping to be among the first oceanographers to peer inside the mysteries of another planet. Th rough WHOI's Exploring Ocean Worlds program, they're currently using oceanographic techniques to study water-rich moons like Enceladus in our solar system. (Another 20 ocean worlds in our solar system are under consideration by NASA, five of which are already confirmed: Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, which are moons of Jupiter; Titan, another moon of Saturn, and Triton, a moon of Neptune.) It's about as distant as any oceanographer could dream of going, even with robotic means.

"Beyond 6,500 meters, there's a whole region of the ocean that's been understudied. We just don't know what's down there."

—Jeff Seewald, WHOI marine geochemist

Julie Huber works closely with German. "The space and ocean science communities have really been coming together to study this over the last few years," she says. "One of NASA's key missions is exploring the origins of life: Where did we come from? Where are we going? How does life adapt to extreme environments? Lots of scientists are trying to answer those questions here on Earth, but now is the first time we're poised to go to another place in our solar system and ask those questions."

Eventually, researchers like Huber and German want to expand on the undersea robotics knowledge that WHOI has already invested decades in developing. Instead of designing autonomous vehicles for the open ocean on Earth, however, they're hopeful they can develop a probe that will operate on its own while submerged beneath the ice of Enceladus.

Creating a robot like this would need to take into account all the insights scientists have gained from studying polar ice and deep vent sites on our own planet. It will need to survive as many as seven years in the vacuum of space, which can reach temperatures that dip near absolute zero (-273 degrees Celsius; -459 degrees Fahrenheit). After that, it'll need to land successfully on Enceladus, dig through several miles of surface ice, deploy itself into the moon's ocean, and find vents autonomously. It's a tall order. But it's something that German, Huber, and other researchers are confident they can handle within the next decade.

German points to WHOI's Nereid Under Ice-or NUI-a new remotely operated vehicle built in 2014. It was designed with a similar mission in mind. Although it can be steered by humans directly over a thin fiber-optic cable, NUI is smart enough to operate autonomously on its missions and return safely to the ship from which it was deployed. Forays like this, German says, are dress rehearsals for such projects farther afield on ocean worlds like Enceladus. He believes those future explorations will help answer one of humankind's most profound questions.

"I don't think civilization could ask a bigger question than 'Are we alone?'" he says. "It's amazing to know that oceanographers have the skill set to potentially answer that question within the coming decades without even leaving our own solar system."