For the Navy, the Coast Isn’t Clear

Oceanographers mobilize to help the Navy operate effectively in complex, shallow waters

Every so often, circumstances can conspire to make a battleship turn on a dime. Fifteen years ago, two geopolitical events prompted the U.S. Navy to abruptly change long-standing research priorities and steer rapidly in a new direction.

When the Berlin Wall collapsed in 1989, so did the Navy’s Cold War necessity to counter the Soviet Union’s huge submarine force throughout the world’s deep oceans. A year later, the first Persian Gulf War shifted the Navy’s interests to landing troops and operating ships in shallow, often mined, coastal waters. The research focus changed from “blue water” to what the Navy dubbed “littoral” warfare.

Oceanography for national defense

One of the strengths of the U.S. Navy has been its ability to exploit the ocean environment in the same way land-based soldiers use the landscape to their advantage. The key is understanding the ocean’s physical and geological properties, a basic research endeavor promoted and funded by the Navy for six decades.

Columbus O’Donnell Iselin, second director of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, was quick to realize the potential symbiosis between oceanographers and the Navy. In August 1940, he wrote a letter to Frank B. Jewett, a member of the newly created National Defense Research Committee, whose charge was to marshal the nation’s scientific resources for an inevitable global war.

“The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution…has been engaged in oceanographic research since 1931,” Iselin wrote. “This memorandum sets forth some suggestions as to how the personnel and equipment of this laboratory can be better utilized for the national defense, for it seems likely that the training and experience of oceanographers will enable them to attack successfully various problems having a naval consequence.”

Thus began WHOI’s long and continuing tradition of research for the Navy. During World War II, Institution scientists investigated many aspects of underwater explosives. They found ways to prevent fouling of ships’ hulls by barnacles, seaweed, and other marine life that caused turbulence and increased fuel consumption—research that lowered the Navy’s fuel bill by 10 percent. They showed how salinity and temperature changes in the ocean affected the propagation of sound under water. They built instruments (bathythermographs) to measure these changes and trained sailors to use them to avoid detection from sonar, which “saved many of our ships,” the Navy reported.

Such wartime research successes led in 1946 to the creation of the U.S. Office of Naval Research (ONR), which funds instrument and technology development and wide-ranging basic research on ocean properties and processes, particularly in ocean acoustics.

Listening for submarines

As in World War II, oceanographic research proved valuable to the Navy during the Cold War. Research begun at WHOI by Maurice Ewing and J. Lamar Worzel culminated in the discovery of the SOund Fixing And Range (SOFAR) channel, a layer of water in the ocean that acts like a pipeline for efficiently transmitting low-frequency sound over vast distances.

The discovery enabled the creation of the Navy’s highly successful SOund SUrveillance System (SOSUS), which could detect submarines by their faint acoustic signals. SOSUS, and more advanced systems derived from it, allowed U.S. forces to track and, if circumstances warranted, engage Soviet submarines.

Countering the Soviet submarine threat was a daunting task, prompting a Navy research investment of about $14 billion per year, but it was a primary Cold War mission. Being able to accurately keep track of Soviet submarines whenever they operated created a powerful deterrent to a shooting war.

A new theater of operations

The end of the Cold War brought a shift in priorities and a major reduction in Navy research funding. But new conflicts emerged, as well as renewed attention to old ones in the Middle East, Yugoslavia, Korea, and Taiwan. These served to refocus the Navy’s attention on learning how to operate safely and effectively in coastal waters, which are extraordinarily challenging for naval warfare.

The properties of the waters from the continental shelf to the coast are fundamentally different from the cold, deep ocean. The simple, stable, and predictable structure of water masses in the deep ocean (such as the SOFAR channel) does not exist in the shallows.

Coastal waters contain water masses with widely different temperatures and salinity levels, and the properties of these water masses are constantly affected by a wide variety of coastal factors and processes—including tides, wind-driven currents, inflows from rivers, changing air temperatures, and mixing between water masses. As the water masses shift, so does the structure of the ocean’s water column and the transmission of sound through it.

The result is a highly complex and dynamic—and highly unpredictable—structure inimical to the Navy’s cold, deepwater acoustic tools and techniques. Shipping noise, fishing activities, and shallow, reverberating seafloor topography add further acoustical complications.

These acoustic difficulties in coastal waters make it hard to detect mines. During the first Persian Gulf War, Iraqis used World War I-era mines deployed from small boats to staunch the movement of U.S. amphibious forces.

Another uniquely coastal danger is bioluminescence. Nutrient-rich coastal waters are full of marine life that glows when excited by movement and can reveal the presence of ships, subs, or Navy SEALs.

As they have since the days before Pearl Harbor, WHOI scientists have mobilized to conduct basic oceanographic research funded by the Navy in this new theater of operations. The four articles that follow highlight some of their work related to littoral warfare.

From the Series

Image

Slideshow

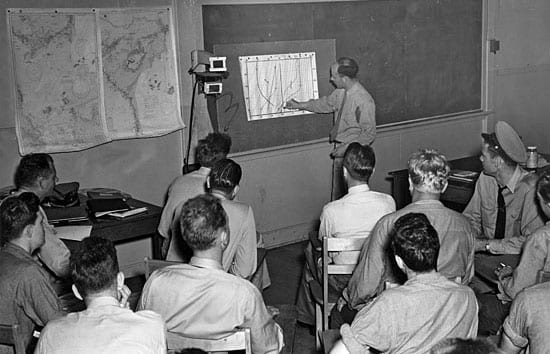

A LIFE-SAVING LECTURE—During World War II, WHOI scientist Dean Bumpus teaches a class of Navy submariners how to use bathythermographs to avoid detection by enemy sonar. The instruments, developed at WHOI, measure ocean salinity and temperature, which affect the propagation of sound under water. (Photo courtesy of WHOI Archives)

A LIFE-SAVING LECTURE—During World War II, WHOI scientist Dean Bumpus teaches a class of Navy submariners how to use bathythermographs to avoid detection by enemy sonar. The instruments, developed at WHOI, measure ocean salinity and temperature, which affect the propagation of sound under water. (Photo courtesy of WHOI Archives)

Related Articles

- An Oceanographer’s Atlas

- A cozy crusade

- 5 WHOI women making waves in ocean science and engineering

- Five idioms for ocean lovers

- Accessible Oceans

- Diverse Voices From Our Maritime Past

- Five books WHOI researchers are reading right now

- On the high seas

- Future Voices: how kids view our ocean in the coming decades