Can environmental DNA help us find lost US service members?

Ocean scientists explore how eDNA may be able to help find and identify lost military personnel in the ocean

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Chelsea Carbonell was working in her garden under a partly sunny Tacoma sky when the call came in. She didn’t recognize the number, but answered it anyway as she stood among a maze of vegetables, herbs, and flowers in her backyard.

"I have really great news for you,” said the caller, a case manager with the U.S. Army’s Past Conflict Repatriations Branch, an organization under the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA). “We found the remains of your uncle!”

Tears trickled down Carbonell’s face. Her Great Uncle, U.S. Army Air Forces 2nd Lt. Ernest Vienneau, had been missing since November, 1944, when the B-17 bomber he co-piloted during World War II came under heavy fire and sank off Vis Island, Croatia.

“This was an open family wound that had gone down generationally,” says Carbonell. “Getting the call was a huge closure, and I felt like there was a breath.”

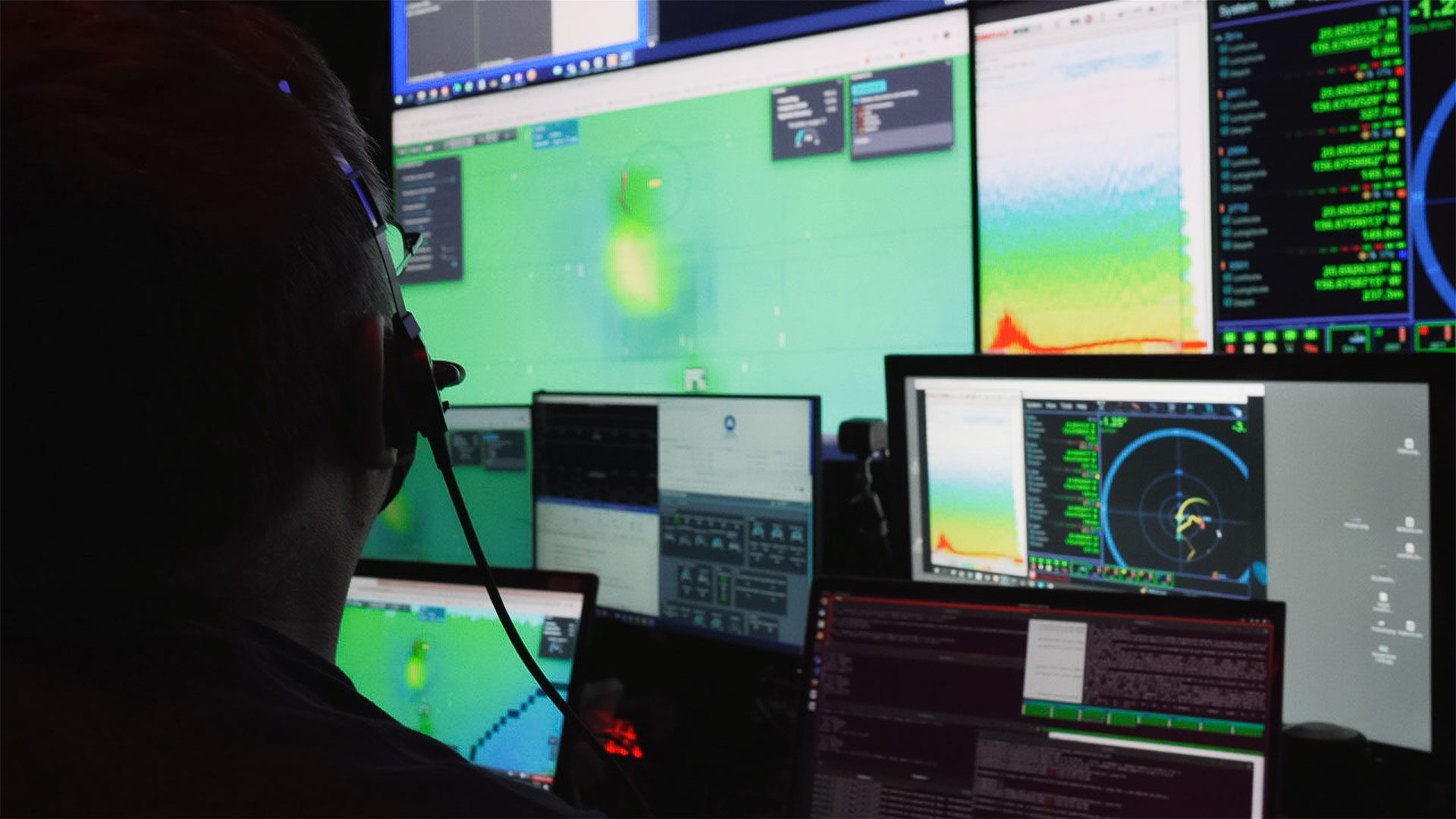

The DPAA is the entity within the U.S. Department of Defense whose mission it is to search for and find U.S. Service members lost in past conflicts and bring them home. Since the organization's inception, it's had considerable success in finding and identifying lost military personnel in the ocean and on land—the agency identifies, on average, several hundred service members every year. But the process is fraught with challenges. Searching the vast ocean for a small downed warplane is work that is often compared to a finding a needle in a haystack, even with the latest in AUV (Autonomous Underwater Vehicle) and sonar technologies. But even when a potential recovery site has been discovered, finding human remains there can be difficult or impossible.

U.S. Army Air Forces 2nd Lt. Ernest Vienneau (Photo courtesy of the Chelsea Carbonell)

“Organic material in the ocean, particularly in warm water, can deteriorate very quickly,” says Hannah Fleming, an innovation specialist supporting the DPAA. “So, there is the chance that an excavation team goes to a site that has associated missing servicemembers and they can’t find any human remains because they’re gone.”

Human remains can also be carried away from crash sites by ocean currents, or decompose from a range of microenvironmental factors including ocean depth, salinity, and oxygen levels.

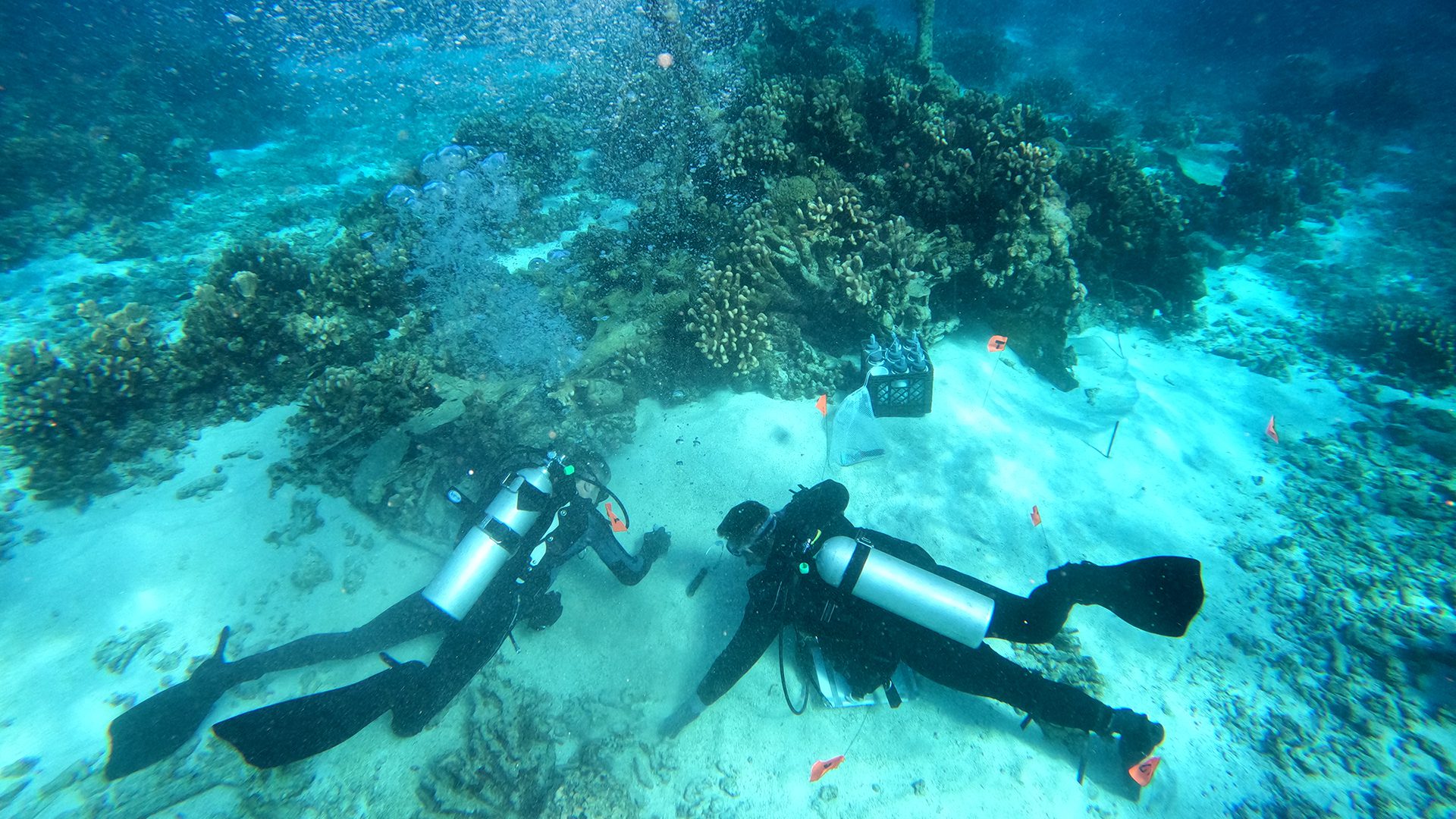

But the DPAA, unwavering in its commitment to get lost servicemembers home, routinely sends excavation teams down to the seafloor anyway. The excavation process itself is often painstaking—picture trying to hover in place a few feet above the murky seafloor, carefully excavating endless amounts of sand as ocean currents push you every which way. And doing it day after day, often for weeks at a time.

The process can also be pricey: a single excavation can require a team of dozens of divers and archaeologists and last several months.

Researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution are now partnering with the DPAA to explore how recent advancements in science and technology might inform the search and recovery process. They’re testing methods to utilize eDNA (short for environmental DNA) which, according to WHOI biologist Kirstin Meyer-Kaiser, may be able to detect traces of human genetic material left behind in seafloor sediments and the surrounding water column.

“We’re trying to find out if we can use environmental DNA methods to determine if there are likely to be human remains at potential recovery sites,” says Meyer-Kaiser. She explains that if there are indications of remains, eDNA results could also be used to map likely locations of human remains across a site.

To test the concept, Meyer-Kaiser sent WHOI scientist Calvin Mires and marine imaging expert Evan Kovacs to three sampling sites in Saipan in March, 2021. There, they worked alongside a broader project team to collect water column and seafloor sediment samples at pre-determined spots. The historical and archaeological record indicate that two of the sites have associated crewmember losses.

Mires and Kovacs took push core samples at each site by jabbing foot-long clear PVC tubes into the seafloor until they were full of sediment. They also collected 60 liters worth of seawater samples at each site.

“In areas where there were likely to be remains, such as the cockpit, we took a higher concentration of samples,” says Mires. “Fortunately, we did not have to dive more than 30-40-feet deep, and the clarity of the water was wonderful. Having good conditions to work in allowed us to focus on the mission, not on the environment.”

Following strict sample processing protocols, the project team shipped the samples from Saipan to the University of Wisconsin’s Biotechnology Center for analysis. Collaborators there are now working to extract genetic materials from the sediment and water samples to explore whether human eDNA can be detected at the site and, if so, what can be learned about its origin and nature. These findings will result in original research that, if successful, could lead to the DPAA developing and employing new eDNA methods for assessing sites in recovery efforts.

In the meantime, researchers from East Carolina University, also in partnership with the DPAA, sent a team of archeologists to use standard archaeological methods to excavate the same three sites to look for associated physical human remains. The site maps generated during the excavation will, ideally, be compared with resulting eDNA cluster maps to identify potential overlap between any genetic traces and the location of recovered potential human remains.

“This is the first time anyone has ever done this,” says Meyer-Kaiser, “so the methods are still under development.”

Acknowledging this project is first and foremost about generating and testing new ideas, Fleming says that she’s tentatively hopeful it will be a success. “It would be ideal if, in the future, we could write up a report during the pre-excavation phase that says we know human DNA is in the sediment, and that we think human remains are within x meters of the samples that were taken,” she says. “I’m very interested to see how this goes—it would be a fantastic addition to our toolkit if it works.”

Perhaps the greatest beneficiaries of a successful outcome would be the families of the brave servicemembers who risked their own lives for the lives of others. Carbonell knows how important the work of the DPAA is. “It’s amazing that people care enough to do that,” she says. And she’s still comforted by not only the fact that her Great Uncle Ernest was found, but that more than 100 family members and friends were able to give him a proper burial last year in Millinocket, Maine.

“He had been down there since 1944,” says Carbonell. “To be at the funeral and have Ernest have his last rites read by the priest was a beautiful thing.”

More than 100 family members and friends attended the funeral for 2nd Lt. Vienneau in Maine in 2021 (Photo courtesy of the Chelsea Carbonell)

This research is a collaborative innovation endeavor, spearheaded by the DPAA, spanning four testbeds around the globe and supported by more than fourteen partners. This story covers actions in one testbed, which included time and resources from the DPAA, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center, East Carolina University, Task Force Dagger Foundation, Florida Public Archaeology Network, Ships of Discovery, Apparatus, and International Archaeological Research Institute Inc.