Coral Coring

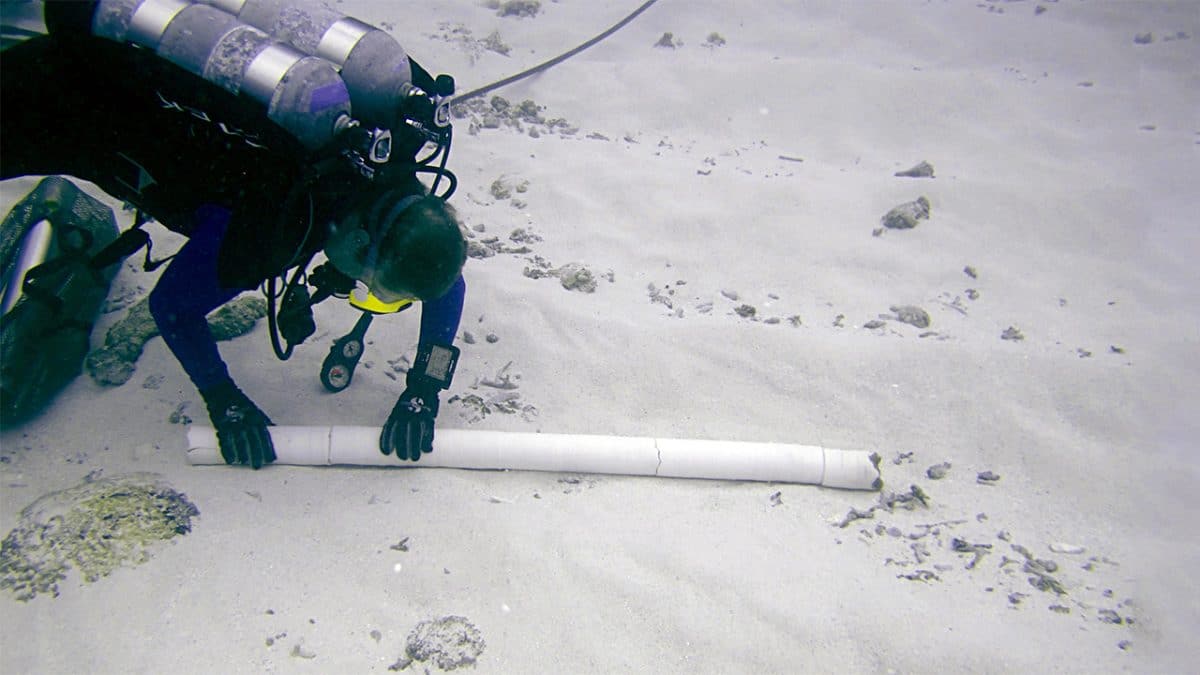

Off a small island in the Chagos archipelago in the Indian Ocean, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) biogeochemists Konrad Hughen and Colleen Hansel use a special underwater drill to take a core sample from a boulder coral (Porites lobata) during an expedition in 2015 (top left).

Porites lobata corals are actually colonies of tiny polyps, like sea anemones, that often grow up to 13 feet tall and live more than 400 years. They secrete calcium carbonate skeletons and live only in a thin layer at the surface of the coral structure. The skeletons are built from chemical components in seawater and grow in annual layers, like tree rings, so scientists can precisely date when parts of the skeleton formed.

Back in the lab at WHOI, scientists can analyze the skeleton chemistry, revealing shifts over time in sea surface temperature, salinity, nearby river runoff, and even pollution at up to weekly resolution. The longer the core, the further back in time the scientists can go—beyond the limits of shorter-term data from modern-day instruments and satellites.

With these detailed core records, the scientists can determine how the climate in these remote regions has changed over the past several centuries and compare patterns with other regions around the world. Their larger goal is to gain more understanding of how Earth’s climate system functions and evolves over time.

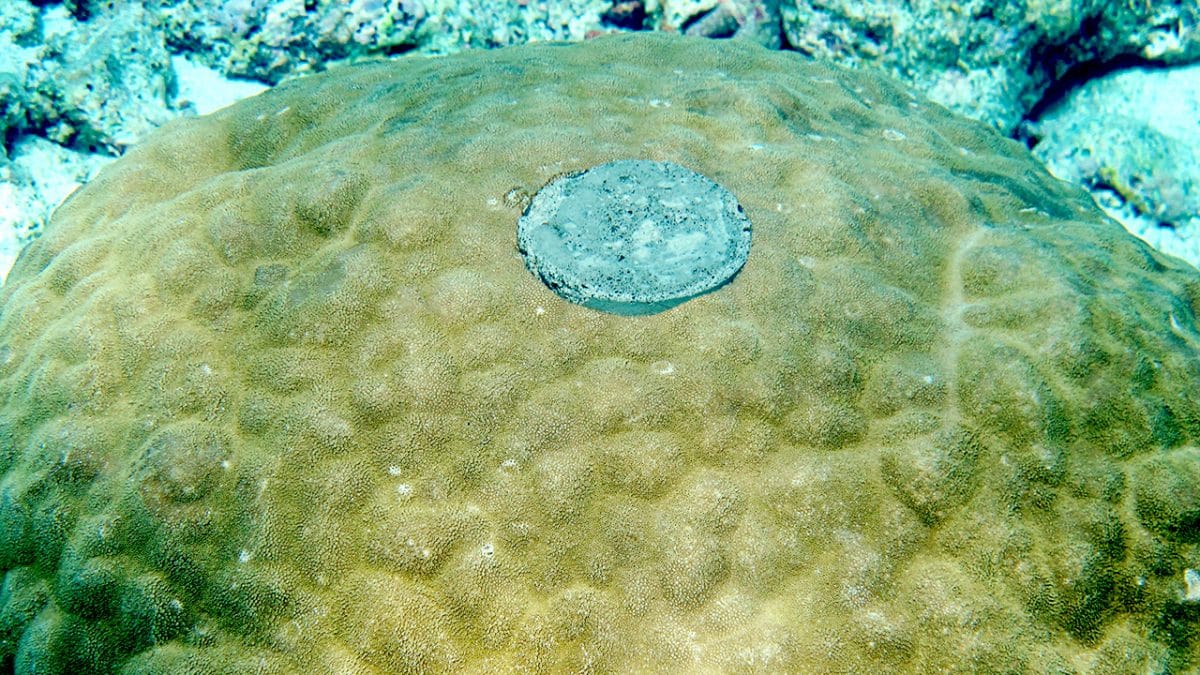

When coring is completed, the scientists cap the hole with a concrete plug. Polyps grow up and over the plug, completely covering and healing the scar within a year or two. Afterward, no one without an underwater X-ray would ever know a core was taken.

This research was conducted during the Global Reef Expedition funded by the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation.