Big Whale, Big Sharks, Big Stink

R/V Tioga sent into action to perform whale necropsy at sea

A shipping tanker first spotted the whale on Sept. 9 about 24 miles southeast of Nantucket, Mass. It floated belly up—species unknown, cause of death a mystery.

Like a detective, Michael Moore, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, scrambled into action. He gathered several sharp flensing knives, like those once used by whalers, to perform a messy but necessary partial necropsy to learn more about the whale. Then he and a team from the Cape Cod Stranding Network and the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration secured a rapid-response research vessel, WHOI’s Tioga.

They set out just after 6 on the morning of Sept. 11—a clear, sunny Sunday—to locate the drifting carcass at sea, guided only by coordinates supplied by the Coast Guard.

After two hours of searching, help came from above: A pilot who was in the area looking for sharks radioed the whale’s location to Tioga. As the vessel approached the animal, Moore saw that he wasn’t the first to arrive on the scene. From Tioga’s bow, he watched dozens of gulls, storm petrels, and shearwaters flocking the bloated carcass, tearing at strips of exposed, sun-scorched skin. What he couldn’t see were the sharks.

“The pilot said, ‘Look, I want you to know that there are at least 200 sharks down there,’ ” Moore said. “He told me there were more sharks than he’d ever seen in one place in 25 years of working at sea.”

Fat, happy sharks

The pilot, Tim Voorheis, who had crewed on a fishing boat for two decades off the New England coast, was hired by a biologist from the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries to spot great white sharks, which are known to feed on dead whales. After three hours of flying, “I was about ready to give up, because I thought maybe the darn whale sank,” Voorheis said. “Then I looked up and saw something, about eight miles away.”

He first noticed the slick—a trail of fishy-smelling oil trailing seven to eight miles from the dead animal and shimmering on the sea surface. “It was loaded with sharks. Makos. Blue sharks. A few dusky sharks. All sizes, including a lot of big ones,” he said. His eyes followed the slick to the dead whale’s tail, where dozens more sharks gathered.

“When we got to the carcass, all we could see was a lot of birds and a couple sharks looming around the carcass,” said Ken Houtler, Tioga’s captain. Voorheis said that he watched most of the sharks scatter when the boat approached.

Still, several remained.

“We saw some very fat and happy blue sharks just sort of lazing around feeding and staying close to the buffet,” said fisheries biologist Tim Cole with NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service in Woods Hole, who assisted with Sunday’s trip. “A dead whale is a huge mass of calories for sharks and other marine animals.”

Searching for clues

Moore has conducted more than 35 whale necropsies, usually on whales washed ashore. In necropsies at sea, he typically works alongside the whale in a small rubber boat deployed from larger vessels.

But not on this Sunday, with sharks in the water.

Houtler maneuvered the vessel alongside the whale. Floating parallel to Tioga, it stretched as long as the 60-foot vessel. It was a female finback, and from its length, Moore estimated that the animal was young, between 13 and 16 years old.

Like a human autopsy, the necropsy would provide clues to why the whale died. The whale may have been struck by a ship or become entangled in fishing gear. Moore also considered another cause that could be investigated at sea: a record harmful algal bloom in coastal waters that spread from Maine around Cape Cod this spring and summer. Some scientists think the toxic algae may have played a role in the deaths this year of at least 22 sperm, minke, fin, and humpback whales.

These toxic algae are consumed by small marine animals called zooplankton and by fish or shellfish. The toxins accumulate in these consumers and are then passed up the food chain to marine mammals. These fast-acting toxins have been known to trigger respiratory failure in humpback whales, so scientists want to know if the toxins cause similar reponses in other whale species.

Searching for evidence of toxic algae in the finback whale, Moore needed access to urine and fecal matter in the animal’s bladder, colon, and intestinal track. He and others aboard Tioga tied a line around the whale’s right pectoral flipper and fluke, or tail, and cinched the whale to the boat’s right side.

Gas buildup from decomposition had caused the animal to bob like an overinflated raft. To relieve the gas pressure, Moore made a series of deep, foot-long cuts—called deflationary stabs—using a knife attached to a long wooden pole. This slowly released the gas, causing the whale to flatten yet remain buoyant.

Making the incision

Leaning over the side of the vessel, Moore worked from bow to stern as he made a 30-foot long incision starting above the whale’s fluke. Moments later, while searching for the bladder, Moore realized he needed to climb on the whale, which—opened and deflated—now resembled a dugout canoe.

Moore donned a wetsuit and rubber dive booties, and after securing a harness and safety line attached to the boat, climbed into the whale’s long incision. “There was a nice valley in which I worked,” he said.

Several sharks lingered nearby, feeding on the whale under the surface. Some appeared with streaks of red paint on their noses and backs after bushing against Tioga’s cherry-colored hull. Moore said they weren’t aggressive. “At no time did the sharks show any interest in my activities. I was careful not to allow any cuttings from the whale to go over the side.”

For the next hour, Moore located the rectum and small intestines, scraping mucus and fluid samples with the blade of his knife into plastic sample jars. Though he failed to find the bladder, positioned under a tough section of muscle, he was able to take skin and blubber samples.

Back on shore, Andrea Bogomolni of the Cape Cod Stranding Network will send the samples to the Center for Coastal Environmental Health and Biomolecular Research in Charleston, S. C.—one of the only labs of its kind in the country—for cultures and toxicology screenings. She said the process that will take several weeks to complete.

Soon after Moore finished the necropsy and returned to the boat, Tioga fled to land quickly. The research team’s concern about the sharks had been overwhelmed by the stench of decaying whale, an odor Houtler called “straight out of a horror movie.”

“Maybe some people will have nightmares about the sharks we saw,” he said. “Any bad dreams I have will come from that smell.”

This project was supported by the Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Event Fund through the Office of Protected Resources at NOAA’s Fisheries Service. Sarah Herzig and Andrea Bogomolni with the Cape Cod Stranding Network also assisted with the project’s coordination and research at sea.

Slideshow

Slideshow

An airplane pilot's view of mako, blue, and dusky sharks, as well as seabirds, feeding on a decomposing finback whale, first seen floating about 24 miles southeast of Nantucket on Sept. 9. The pilot estimated about 200 sharks near the whale during his flight Sept. 11. That afternoon, all but four or five of the sharks scattered when the research vessel Tioga arrived with marine scientists interested in studying the whale. (Photo by Tim Voorheis, Gulf of Maine Productions)

An airplane pilot's view of mako, blue, and dusky sharks, as well as seabirds, feeding on a decomposing finback whale, first seen floating about 24 miles southeast of Nantucket on Sept. 9. The pilot estimated about 200 sharks near the whale during his flight Sept. 11. That afternoon, all but four or five of the sharks scattered when the research vessel Tioga arrived with marine scientists interested in studying the whale. (Photo by Tim Voorheis, Gulf of Maine Productions)- A slick of fishy-smelling oil trailed seven to eight miles from the dead whale. "It was loaded with sharks. Makos. Blue sharks. A few dusky sharks. All sizes, including a lot of big ones," said pilot Tim Voorheis, who was flying Sept. 11, the day of the whale's necropsy. (Photo by Tim Voorheis, Gulf of Maine Productions)

- The female finback whale stretched as long as the 60-foot research vessel Tioga. From its length, biologist Michael Moore estimated that the animal was young, between 13 and 16 years old. (Photo by Tim Voorheis, Gulf of Maine Productions)

- Floating upside down, the whale's belly burned from the sun. Sea birds pecked the exposed skin. (Photo courtesy of Michael Moore, WHOI)

- Note the red paint on the right side of this shark, caused by rubbing against the side of the research vessel. (Photo by Ken Houtler, WHOI)

- Red paint was visible on this shark's nose and back after it brushed by the side of the research vessel. (Photo by Pete Duley, NOAA)

- Gas buildup from decomposition caused the whale to bob like an overinflated raft. To relieve the gas pressure, biologist Michael Moore made a series of deep, foot-long cuts called deflationary stabs (shown at center). This slowly released the gas, causing the whale to flatten yet remain buoyant. Moore made a 30-foot long incision starting above the whale?s fluke, or tail. (Photo courtesy of Michael Moore, WHOI)

- "Once deflated and slit, the carcass was easy to work in...it was like a shallow boat," WHOI biologist Michael Moore said. A wetsuit and rubber gloves and booties offered some protection. Moore said working on the whale, rather than from the research vessel, made cutting and taking samples easier. (Photo by Pete Duley, NOAA)

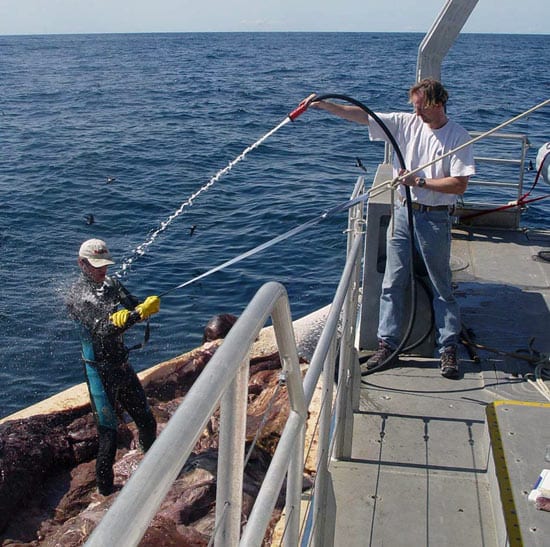

- Though biologist Michael Moore still wasn't minty-smelling even after a wash by Tioga's captain Ken Houtler, the clean spray did remove some of the whale's fluids. Moore holds onto a safety line that secured his harness to the boat. (Photo by Sarah Herzig, Cape Cod Stranding Network)

- Ian Hanley, a crew member on Tioga, got creative with earplugs when overwhelmed by the smell of decaying whale during the necropsy Sept. 11. (Photo courtesy of Michael Moore, WHOI)