Keeping an ear out for whales

Scientists look to safeguard the mammals with robotic buoys in the New York Bight

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2023

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2023

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

It’s easy to forget, standing in the concrete expanse of New York, that the city is a collection of islands. Out on the water, it all makes a lot more sense: a perfect harbor, where river meets sea, tides swirl and eddy, wetlands greet waves from across the ocean.

Long before it was the chosen spot for one of the biggest cities in the world, it was also a great place for whales–before the era of commercial whaling, it’s estimated that there were as many as 21,000 North Atlantic right whales, 20,000 humpback whales, and about 50,000 each of fin and Sei whales in the North Atlantic. As cleaner waters and moving prey make the area attractive to whales once again, they are coming back: all of these species are feeding, migrating, singing, swimming, jumping, and hanging out in the New York Bight.

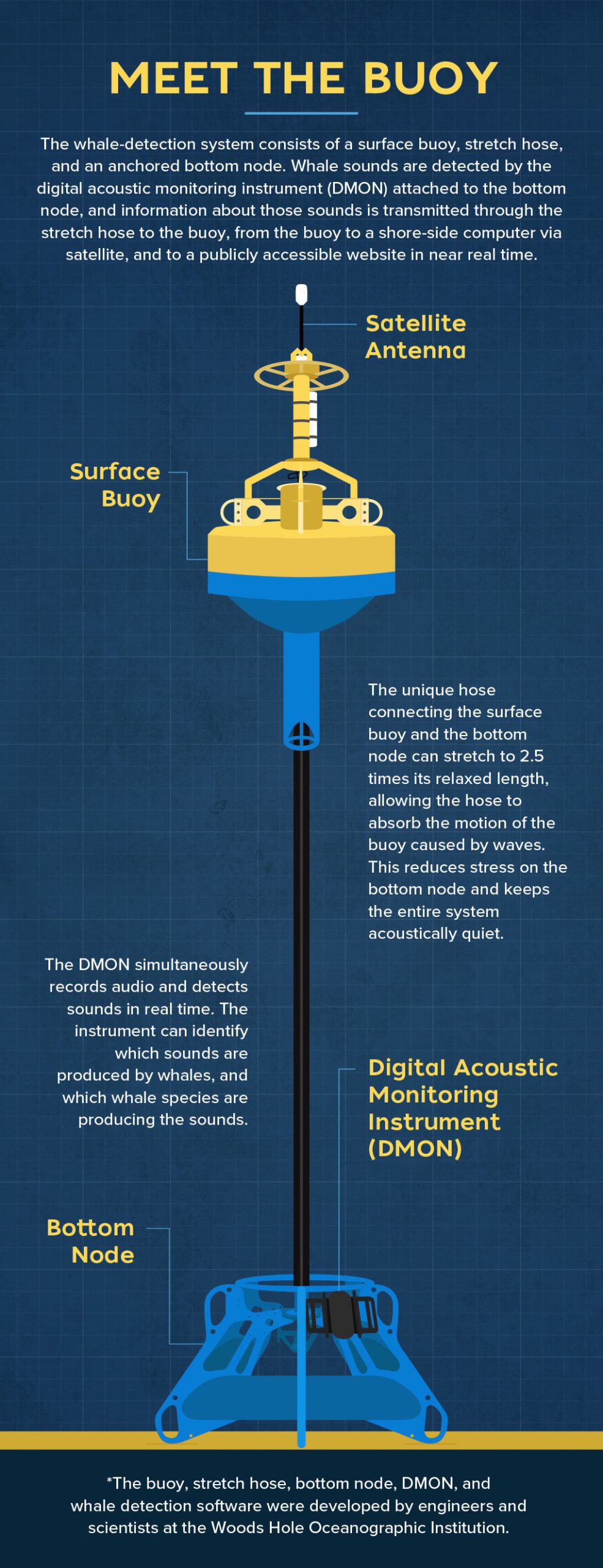

Apart from sightings on newly popular whale watching cruises, whales are letting us know they’re back in town with their songs which are detected by two acoustic monitoring buoys, managed by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), in the Bight, one of the busiest shipping areas in the world.

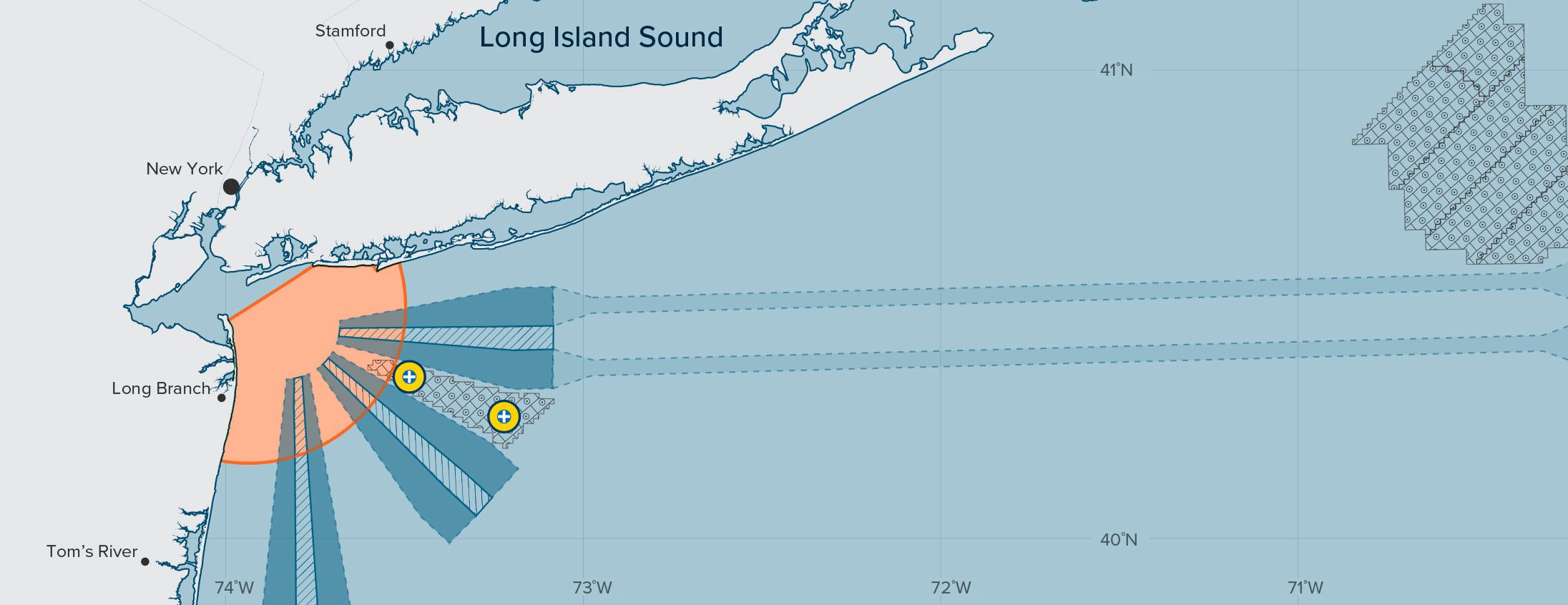

All that activity, paired with the declining number of North Atlantic right whales, now hovering around 340 individuals, was part of the motivation for placing the robotic buoys there, since ship strikes and entanglements with fishing gear are the leading causes of whale death, said Mark Baumgartner, a senior scientist at WHOI.

“We can hear ships going through that area all the time,” Baumgartner said. “It’s not a great place for a whale to be and we wanted to highlight that, and what better way to do it than to use this kind of a system?”

This map shows the WHOI acoustic monitoring buoy sites, wind lease area, shipping lanes, and the North Atlantic right whale Seasonal Management Area (NARW SMA) off the Port of New York and New Jersey. (Illustration by Natalie Renier, WHOI Creative Studio, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Developed by WHOI, the buoys pick up whale songs at various distances, depending on the species (certain species’ calls, at lower frequencies, can travel farther), and send that information to an acoustic analyst, who determines the species and then makes that information available to the public in near real time via

robots4whales.whoi.edu.

Baumgartner and his team also make the updates available to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service, which is responsible for protecting endangered marine species, and shipping companies, which are required to slow down to 10 knots or less in certain areas during specific times of the year to avoid collisions with whales. This speed was derived from several scientific studies in the late 1990s, which suggested that the likelihood of fatalities from ship strikes sharply increases between 10 and 14 knots, among other relevant conclusions. There are also voluntary slowdown requests, known as “slow zones” or “dynamic management areas” that come into effect after a whale is seen or heard by an acoustic buoy, such as WHOI’s, outside the mandatory slow area.

The buoys were deployed through a partnership between WHOI, the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), and Equinor, the Norwegian state energy company that is one of several groups vying to develop offshore wind in the area. The instruments will bob around in the waters for the next six years or so.

The data collected thus far has upended many of the assumptions about whale behavior. Previously, Baumgartner said, scientists thought that right whales made their way up to the Gulf of Maine in the summer, and that many headed south during the winter to calve near Florida and Georgia, and then turned back around in the spring. Instead, they have been seeing whales near New York all winter long. “Our buoy in Atlantic City, New Jersey was our most active,” Baumgartner said.

Howard Rosenbaum, a conservation scientist at WCS who runs their whale program, said, “We knew more about whales and seasonality, and habitat use and population structure in other parts of the world where we had studied whales for a considerable amount of time than we did in the New York Bight,” even though they were practically right outside their offices.

Along with these two buoys, WHOI has six others on the East Coast, and two on the West Coast, all of which are placed within busy shipping areas where whales also like to be, with the hope that shipping companies and others will take notice of the detections, and slow down when whales are present. However, compliance, within both mandatory and voluntary slow zones, has been relatively poor since there are no penalties for noncompliance.

Last year, WHOI’s acoustic systems triggered 46 slow zones in the mid-Atlantic, Baumgartner said. “Most of the protection is needed outside of the mandatory areas, and because we have this voluntary program, we are not providing conservation value with the system.”

“We use this amazing technology to tell everyone and the government puts up this slow zone,” he said, “but is this actually helping at all?”

“We know what the problems are, and we have to go big if we are going to save this species.”

—WHOI senior scientist Mark Baumgartner

Baumgartner and others who work to protect the whales may soon get a better answer to that, as the federal government has begun a new rule-making effort for ships to slow down to protect the North Atlantic right whale, which will expand the mandatory slow areas to much of the coastline between Massachusetts and Florida for any ship over 35 feet in length from November through May.

“That’s a huge deal,” Baumgartner said. “We know what the problems are, and we have to go big if we are going to save this species, but still, it’s remarkable that the federal government has gone forth with this rule.”

It comes at a crucial moment: the ocean is already highly industrialized and becoming more so; North Atlantic right whales are approaching extinction; and 189 humpback whales have died between Maine and Florida since 2016.

However, while the proposed rule received about tens of thousands of supportive signatures, it has received criticism, particularly from the fishing community, who says it will hurt their bottom line.

Senior engineering assistants Jeffrey Pietro and James Rider secure an acoustic monitoring buoy onto a tractor trailer. (Photo by Jayne Doucette, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Additionally, the development of wind energy in the New York Bight and elsewhere on the East Coast is complicating the existing strategies to monitor and protect right whales and other endangered species. The construction of turbines, the laying of transmission cables, and ongoing maintenance will bring more ship traffic and noise to the ocean as well as clean energy to the land.

“From the whale side, clean energy has benefits,” Baumgartner said, as fossil-fuel-caused climate change is just one of the many threats to whale safety and survival, “and we should be exploring how to take advantage of abundant resources like offshore wind.”

However, the proposed development of offshore wind (which has not yet taken place) has been blamed, without any evidence, for the deaths of 13 whales in the last several months in New York and New Jersey, receiving a great deal of media attention.

That many deaths is a crisis, but it’s been one for several years, Baumgartner said. While the number is staggering, it’s actually in line with the number of deaths that have been occurring every year. The difference this time, however, is the connection that people are trying to make to the offshore wind industry, Baumgartner said. Simply stopping offshore wind energy development, without addressing ship traffic and dragging fishing gear, would do nothing to save the whales.

Offshore wind energy will be another industry in the ocean that whales have to deal with, Baumgartner said, but that doesn’t mean it needs to layer on destruction to an already chaotic existence for whales. “Let’s work really hard to do this right,” he said. “Let’s do this in a way that minimizes its impact.”

“Whales suffer from ‘out of sight, out of mind’ syndrome,” Baumgartner said. “Most people don’t think about what’s going on in the ocean, but having these buoys and this system doing this constant reminding has been really impactful, and that was unexpected.”