A Ridge Too Slow?

WHOI team collaborates on Chinese discovery expedition in Indian Ocean

Ever since scientists first discovered vents gushing hot, mineral-rich fluids from the seafloor in the Pacific Ocean 30 years ago, they have found them in various places along the Mid-Ocean Ridge—the 40,000-mile-long seafloor mountain chain where Earth’s giant tectonic plates spread apart and magma rises upward.

Most hydrothermal vent hunts have been confined to the fast-spreading Pacific Ridge and the slow-spreading Atlantic Ridge. But in the past decade, scientists reaching into more remote regions in the Indian and Arctic Oceans have discovered ultraslow-spreading ridges, leaving them to wonder: Can these ridges—spreading apart so slowly they make the speed at which your fingernails grow seem breakneck—produce hydrothermal activity, too?

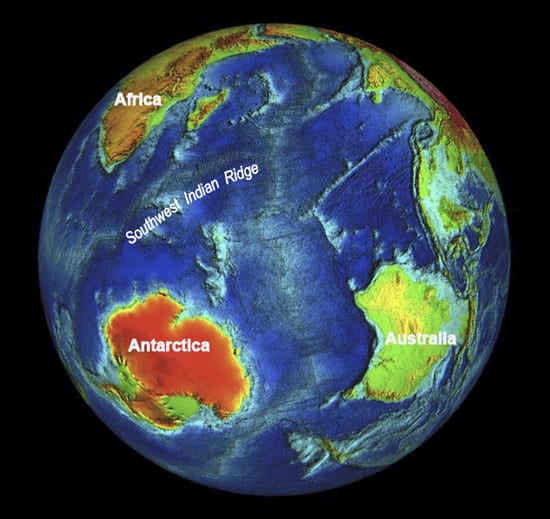

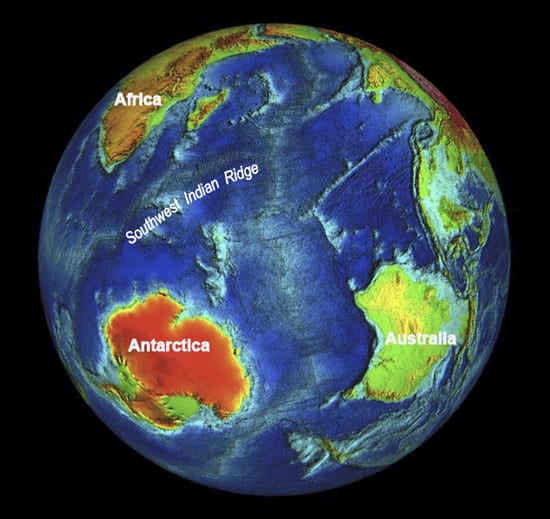

Now an international team of scientists has found one of the largest known hydrothermal vent fields on the ultraslow Southwest Indian Ridge.

“The discovery of the first active vents ever found on an ultraslow-spreading ridge is a significant milestone event,” said Jian Lin, leader of a team of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) scientists who participated in a 20-day expedition aboard the Chinese research vessel Dayang 1 in February and March.

The discovery confirmed a hypothesis that scientists such as Christopher German, chief scientist of the WHOI-operated National Deep Submergence Facility, have harbored for at least 10 years: that vents can form all along the mid-ocean ridge, which zigzags through the middle of the world’s ocean basins like a giant zipper—even in ultraslow-spreading areas. Three years ago, German and Lin further speculated that the slower a ridge spreads, the fewer vents it would have—but the bigger the vent fields would be.

Fast, slow, and ultraslow

The team nailed the discovery with the aid of ABE, WHOI’s Autonomous Benthic Explorer, which has been instrumental in recent years in helping scientists find vents on the bottom of the ocean much more quickly than ever before. ABE, which celebrated its 200th dive on the cruise, acts like a robotic bloodhound: In a sequence of dives, its sensors “sniff out” temperature and chemical clues indicating a plume of fluids from a vent and collect valuable data scientists use to home in on the vent. It also uses sonar to create maps of vent fields and takes photographs about 5 meters above them.

“There’s nothing quite like having 5,000 pictures over one plot of vent real estate to prove what we’ve been saying is true,” German said. The site is at least the size of a football stadium (120 meters by 100 meters) and among the largest known to date.

Peter Rona, a marine geologist at Rutgers University who discovered the first hydrothermal vents on the slow-spreading Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the mid-1980s, tipped his hat to the team: “This is an important discovery that significantly extends our knowledge of seafloor hydrothermal processes to a previously unknown region of the global ocean ridge system,” he said.

Most studies of the chimney-like vent structures have taken place along ridges in the “fast-spreading” East Pacific Rise (100 to 200 millimeters per year) and the “slow-spreading” Mid-Atlantic Ridge (20 to 40 millimeters per year). Only in recent years have scientists explored “ultraslow-spreading ridges” (less than 20 millimeters per year) in the Arctic and Indian Oceans.

The Southwest Indian Ridge vent discovery adds anticipation to an expedition this summer to search for hydrothermal vents under the Arctic Ocean ice on the Gakkel Ridge, the second known ultraslow-spreading ridge, which scientists visited for the first time in 2001. (See "Earth's Complex Complexion.")

An achievement for Chinese oceanography

The discovery was a first for China. “This discovery reflects China’s increasing contribution to ocean science in general, and ridge science in particular,” Lin said.

In 2005-06, as part of China’s first around-the-world oceanographic expedition, Lin had sailed as U.S. chief scientist on Dayang 1 to the Southwest Indian Ridge, where scientists found tantalizing evidence of active hydrothermal venting. They gathered critical data that led them back to the site this year. “People have been looking for vents on ultraslow ridges for more than 10 years,” said Lin, a marine geophysicist and U.S. coordinator of the recent mission.

“The Southwest Indian Ridge was an area where international cooperation could make a difference,” said Lin, and China had the resources to fund a mission to such a remote location, a four-day transit from a port in Durban, South Africa, he said.

The China Ocean Mineral Resources R&D Association (COMRA) in Beijing, China funded last year’s expedition and ABE’s participation in the current one. COMRA, which represents China in the International Seabed Authority, has been exploring the deep sea for mineral resources since the early 1990s.

China is currently increasing investments in ocean science, Lin said. COMRA’s primary interests lay in the large mounds of sulfide deposits created by hydrothermal vents, which are rich in copper, zinc, gold, and other minerals, he said.

“Our Chinese colleagues were the happiest people I’ve ever seen at sea when they brought the first samples aboard,” said Dana Yoerger, scientist in the WHOI Deep Submergence Lab and co-designer of ABE who participated in the expedition. Once ABE pinpointed the site’s exact location and gathered images of it, the Chinese team sent down its “TV grab”—essentially a grappling device guided by a television camera—onto the site.

“They dropped it right on the biggest, baddest structure we had mapped and got a big chunk of a beautiful chimney that was loaded with minerals,” Yoerger said. The Chinese scientists will return to the site early next year with their newly built remotely operated vehicle to see it up close and personal, he said.

Smooth sailing in rough weather

The success of the mission belied its challenging circumstances. A tropical cyclone—the outer wisps of which dealt T. rex-sized sea swells—bee-lined its way toward the Dayang 1, forcing the team to accomplish in less than one week what they had planned to do in two.

Three ABE dives and six days later, and the landmark discovery was in the bag. “It was the most ruthlessly efficient science we’ve ever done,” said German. “We had some of the roughest weather I’ve ever had to deploy and recover ABE in, and we had no margin for error. But we knew this was our only window” to find the vents that they suspected were there, he said.

“We’ve learned our trade with ABE and proved we can do this very difficult science [in remote, challenging locales] using state-of-the-art technology,” said German. The ABE team drew confidence from vent-hunting missions in the last few years to the South Pacific and southern Atlantic Oceans, during which ABE set a high bar for success, German said.

“It also bodes well for our plans to further explore the southern Atlantic into the Antarctic because we need to do more exploring, not less,” German said. A newer and more capable version of ABE—called the Sentry—is slated to debut in 2008.

Culinary culture clash

Yoerger said it was ABE’s third international expedition. “In every one of our international cruises, Phase Zero, as we like to call it [gathering maps of a suspected vent area and plume data indicating a possible vent site], was done by the host country. Then ABE nails it down,” he said. The wealth of data the Chinese scientists already collected from the 2005-06 cruise and another expedition in January-February 2007 was critical to ABE’s remarkable success, as was WHOI engineer Andy Billings learning enough Chinese—“up, down, backwards, forwards, stop, go, and so on”—to ensure ABE was successfully deployed and recovered each time.

Yoerger said he and the rest of the WHOI team enjoyed the cultural challenges of working aboard a foreign vessel. “The Chinese team was exceptional,” he said. “They were sensitive to the fact that we were on strange ground (for us), and they were always trying to accommodate us.”

“It was a burden, but also a great adventure,” he said, “as was the food, of course. I tried not to freak out when I realized there were chicken heads in the dinner stew one night. They’re really very tasty.”

The Chinese science party was led by chief scientist Chunhui Tao, a geophysicist at the Second Institute of Oceanography in Hanzhou, China. The WHOI team included Lin, German, Yoerger, Billings, and Al Duester. “The two international teams worked exceedingly well for this kind of complex operation,” Lin said.

This research was funded by China Ocean Mineral Resources R&D Association, the Census of Marine Life’s ChEss program on Deep-Water Chemosynthetic Ecosystems, and the Charles D. Hollister Endowed Fund for Support of Innovative Research at WHOI.

Slideshow

Slideshow

The Southwest Indian Ridge is a spreading center between the African tectonic plate, (top left, yellow-orange) and the Antarctic plate (bottom left, red). (Image by NOAA Geophysical Data Center)

The Southwest Indian Ridge is a spreading center between the African tectonic plate, (top left, yellow-orange) and the Antarctic plate (bottom left, red). (Image by NOAA Geophysical Data Center)- The Chinese research vessel Dayang 1, which means "big ocean," was used in the discovery of the first hot vents on the Southwest Indian Ridge. (Photo by Mr. Huisheng Lu of R/V Dayang 1)

- WHOI team members (left to right) Al Duester, Andy Billings, and Christopher German recover ABE from one of its three dives in the Indian Ocean. (Photo courtesy of InterRidge program)

- The Chinese research team celebrates two "firsts": making the first Chinese discovery of a hydrothermal vent site, and retrieving the first mineral-rich samples from a vent site on the Southwest Indian Ridge. (Photo courtesy of Dana Yoerger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Three members of the WHOI team: Christopher German, Jian Lin, and Dana Yoerger stand before the WHOI ABE underwater autonomous vehicle on the deck of the R/V Dayang 1. (Photo courtesy of InterRidge Program)

- Jian Lin, leader of the WHOI team (right), and Mr. Songgang Zhen, captain of R/V Dayang 1, stand before the WHOI ABE vehicle. (Photo by R/V Dayang 1 science party)

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Worlds Apart But United by the Oceans An interview with Jian Lin from Oceanus magazine

- A 'Book' of Ancient Sumatran Tsunamis Historic Chinese cruise brings back clues to old earthquakes and new vent sites (from Oceanus magazine

- ABEThe Autonomous Benthic Explorer from Oceanus magazine

- ABE Homepage