What’s Living in the Ocean?

Ten-year Census of Marine Life discovers wealth of new species and explores biodiversity

In 2010, as the United States conducted its latest decadal population census, marine scientists completed their first census to discover the abundance, diversity, and distribution of organisms living in Earth’s oceans. Launched in 2000, the Census of Marine Life evolved into a $650 million project involving more than 2,700 researchers from 670 institutions and 80 nations. Some 540 expeditions assessed different slices of the ocean—from polar seas, coastal zones, and the open ocean to seamounts and other seafloor habitats—and recorded life ranging from large fish to bacteria.

Nearly 30 million observations of thousands of species were made and archived in the newly created Ocean Biogeographic Information System (OBIS) database, the world’s largest open-access, online repository of marine life data. At least 1,200 new species were discovered; some 5,000 other potentially new species remain to be studied and officially named.

The idea for the census germinated in a discussion at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in the summer of 1996 between Fred Grassle, a biologist formerly at WHOI and now at Rutgers University, and Jessie Ausubel, vice president of programs of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and adjunct scientist at WHOI. The Sloan Foundation provided $75 million to launch the program, and scientists specializing in diverse marine animals organized themselves into subgroups, using a broad range of methods and technology to carry out the census work.

WHOI scientists were key contributors, helping to guide explorations of life in various ocean habitats. WHOI biologists Peter Wiebe and Larry Madin, for example, were on a steering committee for the Census of Marine Zooplankton (CMarZ), a project aimed at assessing the diversity of zooplankton from seafloor to surface, including tiny shrimplike crustaceans, swimming snails and worms, and gelatinous animals that spend their lives drifting through the water, often far from shore. Estimated to total more than 7,000 species, zooplankton are vital parts of ocean food webs.

CMarZ was co-led by Ann Bucklin, a biologist at the Marine Sciences and Technology Center at the University of Connecticut and a visiting investigator at WHOI. WHOI researcher Nancy Copley coordinated the CMarZ effort among different countries.

Scientists confirmed 66 new species discovered during CMarZ, and many more collected animals await analysis to determine if they also are new species. Scientists collaborating with CMarZ participated in more than 80 research cruises from 2004 to 2009, funded by agencies in their respective countries. Using techniques that ranged from scuba diving and nets to technologically advanced deep-diving remotely operated vehicles, they collected, photographed, and identified the animals.

Wiebe co-led a landmark cruise across the tropical Atlantic Ocean, during which researchers collected more than1,000 kinds of zooplankton, including many species never seen before. While at sea, taxonomists identified the organisms under microscopes while other researchers sequenced their genes to create unique DNA “bar codes” to identify species.

“Genetic bar codes are a big step forward,” Wiebe said. “We are providing the stepping-stones so future generations can use the results of this project as a benchmark to measure at a glance how ecosystems are changing in the future.”

Madin led a 2007 expedition to explore the Celebes Sea, east of Borneo, and collected samples of what turned out to be a new genus of animals nicknamed “squidworms.”

Life in chemical-fueled ecosystems

Meanwhile, another group of scientists, called ChEss for “chemosynthetic ecosystems,” focused on seafloor animals that obtain energy from chemicals rather than sunlight. Such ecosystems exist at hot geysers of chemical-laden water called hydrothermal vents, as well as other locations where chemicals seep from the seafloor, and whale falls, or remnants of whale carcasses slowly releasing chemicals.

The ChEss project focused on setting up web-based data pages for species from deep-water chemosynthetic systems and developing a long-term international field program for exploring vents and seeps, said WHOI marine geochemist Chris German, head of the National Deep Submergence Facility and co-leader of ChEss.

“We selected priority sites for exploration on the seafloor and mid-ocean ridge,” German said. “We came up with a plan for about a half a dozen sites around the planet where it would be really interesting to know what was living around the hot springs.”

Using remotely operated and autonomous underwater vehicles and advanced imaging systems, ChEss scientists explored Earth’s hardest-to-reach places. German led an expedition in 2010 to the Mid-Cayman Rise, using WHOI’s hybrid robotic vehicle Nereus to explore the region for the first time and finding evidence for the deepest-known hydrothermal vents.

Since 2002, scientists have logged information on more than 500 species and described more than 200 new deep-sea species. In 2005, scientists diving in the WHOI-operated submersible Alvin found a white crab with long, hairy arms on the seafloor 1,000 miles from Tahiti, which they dubbed the “yeti crab.” It turned to out to be not just a new species but part of a new family on the tree of life.

“I think the biggest result was that we got researchers together, to communicate and examine holistic problems,” said WHOI deep-sea biologist Tim Shank, who is a member of the ChEss International Steering Committee. “That has given us leaps in understanding.”

Revealing seamount biodiversity

Shank was also part of the secretariat for Global Census of Marine Life on Seamounts, or CenSeam, which began in 2005 to gather existing information from the international community of scientists studying life on undersea mountains.

Seamounts are common around the globe, yet fewer than 200 of the estimated 100,000 seamounts have been studied. Many support productive ecosystems in less productive regions of the ocean. They also are also highly vulnerable to overexploitation and physical damage by fishing and mining practices.

Shank said that much of the information already collected on seamounts was scattered in different places. “For seamounts, a lot of international work was being done, and species being collected in different ways and species lists being made,” he said. “So the first goal of CenSeam was to pull information from old data, to get it together and translated. For our group, there were so many nations, so diverse, and so many back collections.”

Data analysis and standardization are large parts of the program, and the integrated seamount database CenSeam established will help to align research done in different places and make possible comparisons of biodiversity at seamounts in different regions.

Other CenSeam goals were to learn what factors drive the species diversity on seamounts and how the communities function, and to delineate the impacts human activities have on seamount communities. Rather than try to sample all the world’s seamounts—an impossible task, given the resources available—CenSeam scientists want to guide future seamount sampling to fill gaps in knowledge of regions and types of seamounts.

“The Census of Marine Life means different things to different people,” said Shank. “While a species list was something we did for the ChEss project, we didn’t have that for seamounts, and didn’t try to do it. We had so many diverse researchers all over the world, and it was our goal to enable them to be connected and exposed to each other, to be open and informative.”

“The scientific community now knows it can work together internationally, and there is little doubt that future collaborations will follow,” said Paul Snelgrove of Memorial University of Newfoundland, who is leader of the Census Synthesis Group. Scientists involved in the Census feel an urgency about continuing this work, he said, since global climate change may be causing declines in some species and altering ecosystems.

–>

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Researchers found giant filamentous (strand-forming) bacteria living in oxygen-deficient, high-sulfur sediments of the eastern South Pacific. This new species may use chemicals as an energy source. (Photo by Carola Espinoza, Universidad de Concepción, Chile.)

- Tiny drifting crystalline globes are colonial forms of single celled organisms called radiolarians, collected deep in the Celebes Sea off the coast of the Philippines. White individual cells dot the outer surface of the colonies' geodesic dome-like structures made of glassy slivers of silica. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- First seen in 2002, a foot-long 'comb-jelly,' or ctenophore, clings to the floor of the ocean's abyss by one stretched tentacle. Comb-jellies are fragile gelatinous animals found in all oceans. Photographed by a remotely operated vehicle at a depth of 7,217 meters (4.48 miles) in the Ryuku Trench off Japan, this new species holds the record as the deepest living ctenophore. (Photo courtesy of JAMSTEC-CMarZ.)

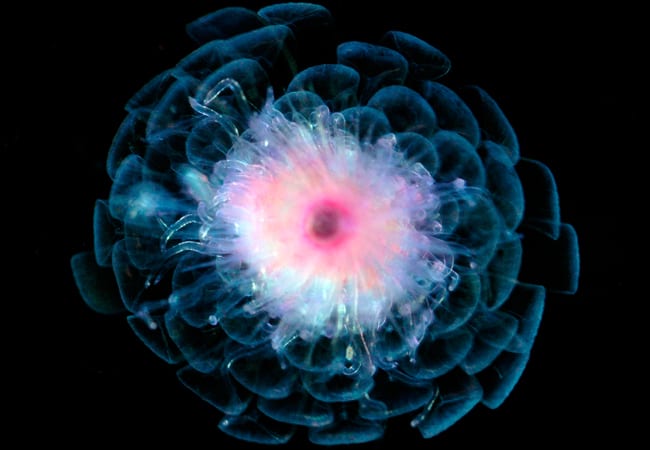

- What appears to be a delicate pink flower is instead a carnivorous animal that catches prey with stinging cells. A relative of jellyfishes, Athorybia rosacea is only an inch wide. It was collected near the sea surface by SCUBA divers on a Census of Marine Zooplankton cruise in the Sargasso Sea. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- Researchers surveying marine life of the Arctic Ocean were surprised to find a completely unknown but abundant species of jellyfish, at depths below 1000 meters (3,280 ft). Hundreds of the new species Bathykorus bouilloni were observed with a remotely operated vehicle. (Photo copyright of Kevin Raskoff, Monterey Peninsula College.)

- In 2007, scientists using a remotely operated vehicle to explore the deep Gulf of Mexico sea floor below 1,000m (3,280 ft) observed this spiral sea-whip coral, located in an area named Coral Garden. This single coral harbored several other kinds of organisms living in association with it. (Image courtesy of Aquapix and Expedition to the Deep Slope 2007.)

- This worm, a new species, was collected on a whale fall, 925 meters (3,035 feet) deep in Sagami Bay, Japan. A “whale fall” is a whale carcass that has sunk to the ocean floor, serving as a source food for deep-sea species, including some of the same animals found at chemical seeps. (Photo by Yoshihiro Fujiwara/JAMSTEC.)

- In 2007, U. S. and Filipino scientists searching the deep water of the Celebes Sea for new species discovered this unusual 4-inch worm swimming 2,800 m (1.7 miles) down. They nicknamed the new species “Squidworm” before it was given its scientific name: Teuthidodrilus samae. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- A snail whose shell is completely covered in rows of hair-like projectons was collected at a deep hydrothermal vent at Suiyo Seamount off Japan. The specimen is probably a new species, and is the only one of its species found thus far. Like many animals living at vents, the snail harbors chemosynthetic bacteria in its tissue. (Photo by Yoshihiro Fujiwara/JAMSTEC.)

- Scientists collected this six-inch squid at depths near 1,000m (3,000 ft) in the Sargasso Sea during a landmark Census of Marine Zooplankton expedition to identify and analyze genetic material of planktonic animals in the Atlantic Ocean. Its two eyes are of different sizes, and it is covered with pigment-bearing spots that enable it to change its color and appearance. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- A red shrimp-like animal, one of several species called krill, was collected on a Census of Marine Zooplankton expedition to the Sargasso Sea to survey, identify, and genetically barcode, or type, animal plankton. Krill are critical links in ocean food webs, eaten by animals from fish to whales. (Photo by Nancy Copley, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- In the inhospitable, chemical-laden environment of a hydrothermal vent in the deep southeast Pacific near Easter Island, Census of Marine Life explorers discovered a new species of crab covered with long white fur. Soon nicknamed the Yeti crab, the six-inch Kiwa hirsuta belongs to a new family, genus, and species. (Cindy Van Dover, Duke University Marine Laboratory.)

- A new species, a blind lobster with long, oddly-shaped claws, was collected on the seafloor at about 300m (984 feet) during the MNHN/USNM/BFAR AURORA 2007 expedition off the Philippines. Its scientific name is Dinochelus ausubeli - derived from the Greek dinos, meaning terrible, chela, meaning claw, and ausubeli, honoring Jesse Ausubel, a co-founder of the Census of Marine Life. (Photo by Tin-Yam Chan, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung.)

- Copepods are tiny swimming animals that reach great abundance seasonally in the ocean and are a main source of food for many fishes and marine mammals, including whales. Census researchers in the Arctic Ocean found this bright orange copepod, Lucicutia aurita, below 1000m (3,280 feet) depth. (Photo by Russ Hopcroft, UAF/NOAA/CoML.)

- Called “sunflower stars,” three bright blue sea stars Pycnopodia helianthoides crawl over the green seafloor in shallow waters off Knight Island in Prince William Sound, Alaska, USA. These large, fast-moving sea stars can grow to a meter across and can have as many as 24 arms. (Photo by Casey Debenham, University of Alaska Fairbanks.)

- A team of U.S. and Filipino scientists captured this transparent swimming sea cucumber over 1.5 miles down in the Celebes Sea. After eating bottom mud, it swims up into the water by undulating the frilly collar around the top of its body. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- Scientists surveying deep-sea life on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and using a remotely operated vehicle to explore depths between 700 meters (2,296 feet) and 3,600 meters (2.24 miles) collected several new deep-sea species of a little-known animal called “acorn worms” (or enteropneusts). Acorn worms lack a brain, eyes, or organs, but have a head and tail end, and worms may be transitional between invertebrates and backboned animals. The scientists discovered three distinct species, colored pink, purple, and white, and saw the animals feeding, moving, and leaving characteristic spiral traces on the sea floor. (Photo courtesy of David Shale.)

- Snaking through the upper levels of the ocean, a long chain-shaped colony of linked one-inch-long animals called salps swims by jet propulsion—each animal takes in water at the front and forces it out the back, causing forward motion. This chain of Salpa aspera was captured by SCUBA divers, then identified and genetically typed by researchers on a Census of Marine Zooplankton cruise in the north Atlantic. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

- Exploring deep seamounts and ridges, a June, 2003 expedition north-west of New Zealand captured this fish, called a “fathead” Psychrolutes microporos, between 1013 meters (3,323 feet) and 1340 meters (more than 2 miles) deep on the Norfolk Ridge. (Photo copyright NORFANZ Founding Parties, Photo by Kerryn Parkingson, additional thanks to Peter McMillan and Andrew Stewart.)

- Census of Marine Life researchers surveyed and tracked large predatory fish that are declining in population, such as these Bluefin Tuna Thunnus thynnus. (Photo courtesy of Richard Hermann-Galatée Films.)

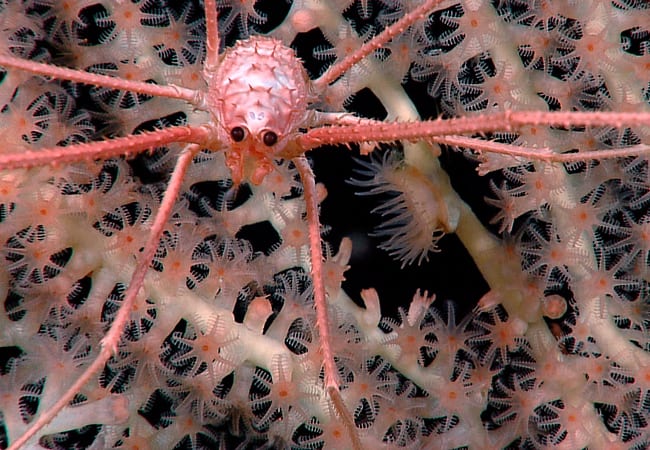

- During the ten-year Census of Marine Life, other agencies and partnerships also carried out explorations of Earth's oceans and helped document the seas' biodiversity. For example, a 2010 joint U.S.-Indonesian expedition, supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric administration Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, surveyed and made video records of species in a part of Southeast Asian waters known as the “Coral Triangle” that is considered the most diverse ecosystem in the world. Seen at 704 meters (2,310 feet) depth on a newly-mapped seamount, this crab with 8-inch arms is a species only observed living on soft coral. (Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, INDEX-SATAL 2010.)

- In the waters of the “Coral Triangle,” region of Southeast Asia, researchers on a joint U.S.-Indonesia expedition to survey marine life in this richly diverse area observed this sea lily (a crinoid, related to sea stars) at 1,876 meters (1.17 miles) deep on the Kawio Barat submarine volcano. With its arms pointed in the direction of the current, a sea lily captures food particles drifting by. The image was captured by the Little Hercules remotely operated vehicle. (Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer program, INDEX-SATAL 2010.)