A Sea Change in National Ocean Policy?

Sweeping reforms recommended by two national commissions stall in the harbor

Early in the new century, two national commissions conducted the first thorough reviews in a generation of the nation’s policy for the oceans. Their two reports were received with fanfare and almost universally embraced. But five years later, the commissions’ recommendations languish somewhere between hype and hope.

In 2003, the Pew Oceans Commission recommended significant changes “aimed at guiding the way in which the federal government will manage America’s marine environment in the years ahead.”

In 2004, the U.S. Commission on the Oceans, submitted 212 recommendations “for a coordinated and comprehensive national ocean policy.” This group called on the president and Congress to “take decisive, immediate action to carry out these recommendations, which will halt the steady decline of our nation’s oceans and coasts.”

The proposed 2009 budget for ocean science, however, offers little impetus toward these goals.

Sure, President Bush called for a 13.8 percent increase in National Science Foundation funding for ocean sciences, from $310 million in fiscal year 2008 to $353 million in 2009. And yes, for the first time in the last five years, the proposed ocean research budget for the U.S. Navy includes a healthy increase, from $506 million in 2008 to $528 million in 2009.

But similar budget increases proposed last year by the president and the U.S. House of Representatives were largely erased in the omnibus appropriations bill for 2008 that eventually was passed.

The construction phase of the $330 million Ocean Observatories Initiative, to establish sustained networks of ocean-monitoring stations, has been postponed until 2010 under the current budget proposal for 2009. (The OOI includes a $97.7 million project led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and involving Oregon State University and Scripps Institution of Oceanography.)

Proposed funding for several ocean programs operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) actually decreased. And making matters worse, the National Atmospheric and Space Administration is transitioning operations of earth-observing satellites to NOAA, which may have to redirect ocean science funding to space.

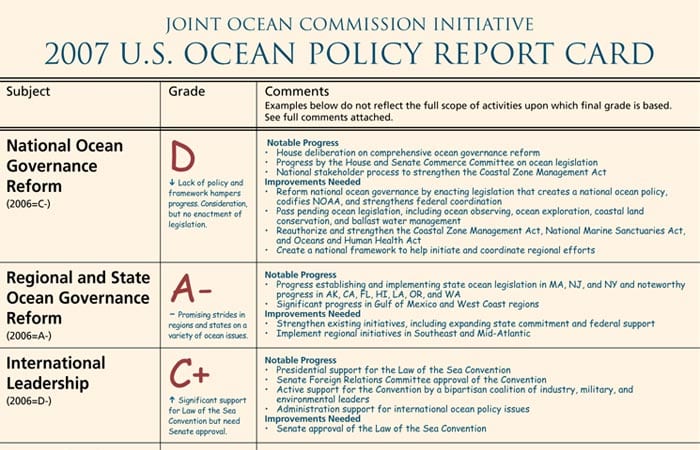

In February, a group named the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative, comprising former members from the Pew and U.S. ocean commissions, issued a report card assessing the nation’s collective progress in ocean policy during 2007. It’s overall grade: a C, with a D+ for new funding for ocean policy and programs.

“Unfortunately, stagnant funding remains the major constraint to making substantial progress in addressing the problems facing our oceans and coasts,” the report card stated.

Setting the bar

All the talk about ocean policy began when Congress passed the Oceans Act of 2000, which established a commission to develop recommendations for a coordinated and comprehensive national ocean policy. The president appointed 16 members from the public and private sectors who were nominated by bipartisan leadership in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.

Over the two years that followed, this U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy conducted 16 public meetings around the country and 18 regional site visits, receiving 1,900 pages of oral and written testimony from some 447 people.

“Like any good researchers, we wanted the best data and statistics we could possibly collect before acting in any way,” said one commissioner, Vice Admiral Paul Gaffney (Ret.), former chief of naval research and now president of Monmouth University in New Jersey.

The U.S. ocean commission outlined opportunities for reforms in national, regional, and state ocean governance, fisheries management, and ocean research and education. Its 212 recommendations included:

- The establishment of a National Ocean Council within the executive office of the president to provide high-level attention to ocean and coastal issues, develop policies, and coordinate their implementation.

- An executive order directing all federal agencies with coastal- and ocean-related functions to improve regional coordination.

- The development of an Integrated Ocean Observing System to substantially advance our ability to observe, monitor, and forecast ocean and coastal conditions.

- The doubling of ocean and coastal research budgets over the next five years.

“With so many smart people saying the same thing, it was clear we were at a tipping point,” said Rick Spinrad, assistant administrator for research at NOAA. “The status quo of our nation’s stance on ocean policy simply wasn’t good enough anymore.”

A history lesson

Most people in the ocean policy world believe this change was long overdue.

The last comprehensive review of U.S. ocean policy was conducted 35 years ago by the U.S. Commission on Marine Science, Engineering and Resources, known as the Stratton Commission, after its chairman, Julius Stratton, the former president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It issued recommendations that laid the foundation for federal ocean policy, including the establishment of national marine sanctuaries, management of marine fisheries, and creation of NOAA.

“The Stratton Commission was really the first to get people thinking about ocean policy in a cohesive and coherent way,” says Gerhard F. Kuska, director of ocean and coastal policy for the White House Council on Environmental Quality.

But by the year 2000, with growing coastal populations and increasing pressures on marine resources, scientists and policymakers agreed it was time for a new commission to weigh in on the state of U.S. ocean policy. Thus, the U.S. ocean commission was born. Around the same time, the Pew Charitable Trusts, a nonprofit organization in Philadelphia, launched its own commission to review ocean policy.

The two commissions operated independently, chaired respectively by Adm. James Watkins, former U.S. chief of naval operations and scretary of the U.S. Department of Energy (the U.S. ocean commission) and Leon Panetta, former U.S. representative and chief of staff for President Clinton (the Pew commission). Then, when the U.S. ocean commission disbanded in 2004, members of both commissions joined to form the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative, co-chaired by Watkins and Panetta, with a mission “to accelerate the pace of change that results in meaningful ocean policy reform.”

Fiscal year ’09 and beyond

To this end, the Initiative’s work continues. This year, after digesting the president’s proposed 2009 budget, joint commission members published their annual report card on U.S. ocean policy for the year 2007. The 20-page document doles out letter grades for seven areas of ocean policy (see below).

“Despite a continuing dialogue regarding funding needs, the flat budgets endured by most federal ocean and coastal programs over the past four years are at the core of the slow pace of national ocean policy reform,” the document read.

But despite insufficient funding, many joint commission recommendations—on fisheries management, coastal development, pollution of urban harbors, and the growth of marine resources industries, for example—might be achieved with political will and grass-roots attention, said Andy Solow, director of the WHOI Marine Policy Center.

“I don’t mean to imply that we don’t need any money, but we can make significant progress in some of these areas without it,” he said. “The right people have been thinking about this stuff. It’s probably time for a little action.”

Slideshow

Slideshow

In 2000, President Bill Clinton (seen here with former WHOI President Bob Gagosian) came to Martha's Vineyard to sign the Oceans Act of 2000. The legislation established a national commission to develop recommendations for a coordinated and comprehensive national ocean policy. (Photo by Susan Gagosian)

In 2000, President Bill Clinton (seen here with former WHOI President Bob Gagosian) came to Martha's Vineyard to sign the Oceans Act of 2000. The legislation established a national commission to develop recommendations for a coordinated and comprehensive national ocean policy. (Photo by Susan Gagosian)- Adm. James Watkins was chairman of the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy and now co-chairs the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative with Leon Panneta (below). Watkins is a former U.S. chief of naval operations and secretary of the U.S. Department of Energy. (Photo courtesy of the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative)

- Leon Panetta was chairman of the Pew Oceans Commission and now co-chairs the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative with Adm. James Watkins (above). Panetta is a former U.S. representative and chief of staff for President Clinton. (Photo courtesy of the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative)

Related Articles

- Navigating new waters

- On the Move

- From Northern California to Ocean Engineer

- In the Ocean Twilight Zone, Life Remains a Mystery

- New glider design aims to expand access to ocean science

- Gift enables new investments in ocean technologies

- Can seismic data mules protect us from the next big one?

- Life at the Edge

- Ocean Observatories Initiative

See Also

- Joint Ocean Commission Initiative

- U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy

- Pew Oceans Commission

- Ocean Observatories Initiative from the Joint Oceanographic Institutions