New glider design aims to expand access to ocean science

Gliders are vehicles vital to collecting oceanographic data, but not accessible to everyone in the ocean community. A team of WHOI engineers want to change that

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2021

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2021

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

In 2018, close to midnight on Martha's Vineyard, engineer John Reine couldn't sleep. His hands, plunged into a watering trough on his family's farm, were dunking a homemade version of a common, data-collecting submersible known as a glider-praying it would work. If it did, Reine would have proven to himself that one of ocean science's most versatile tools would be simple enough for most engineers to build from scratch. At 1 a.m., the glider, powered by hydraulics from a CamelBak water pouch squeezed by Reine, began to rise and fall at his command.

"It was enough for me to say, 'Okay, these aren't that hard to build from scratch,'" says Reine, a lead electronics engineer for the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) at WHOI.

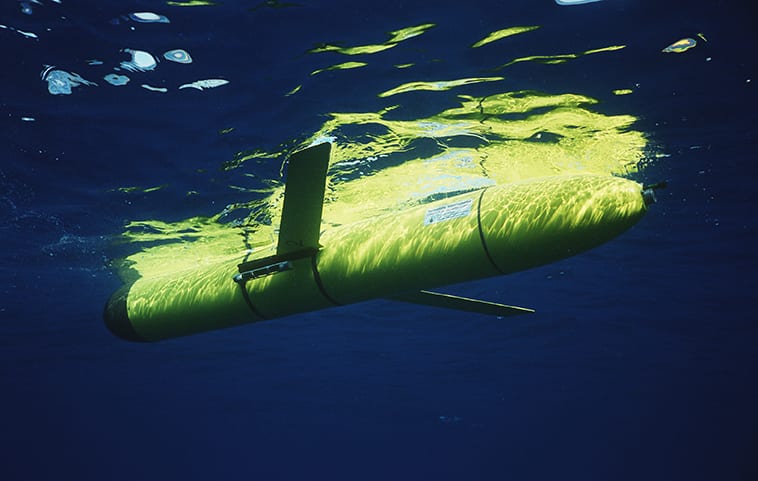

Invented in the 1960s, ocean gliders have become a linchpin for oceanographic data collection. As their name and torpedo-shape suggest, they glide up and down through different layers of the ocean, using a payload of sensors to measure water temperature, salinity, and marine chemistry. These days, they've been crucial for filling important data gaps at ocean depths where stationary observation moorings can't reach.

But Reine says there's a problem: Right now, there's only a few places where you can purchase and service gliders or their parts-for WHOI, a conglomerate known as Teledyne Technologies. That's created a bottleneck for scientists trying to get the instruments out to sea quickly.

Glider testing onboard the R/V F/G Walton from the University of Miami. (David Fratantoni, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

"It turns out, our problems putting gliders in the water were not all technical things, like leaks," says Reine. "Some of them were logistical."

There was a time when the building blocks of the WHOI glider were made solely in-house. Today, those parts are custom-made from outside vendors, making it difficult for Reine and his colleagues to make routine tweaks. Even minor changes to a vehicle's sensors or hydraulic fittings could result in the OOI staff waiting at the back of a long queue, while Teledyne works hard to process their order and the service requests of other institutions.

After sending their own vehicle in for repairs last month, an OOI team headed by engineer Peter Brickley was notified that the vehicle would not make it back to them in time for their research cruise to Alaska this summer.

"We couldn't get repairs done in time, but you can't lay [that problem] all at the feet of the vendors," says Brickley.

Now down a vehicle, he anticipates a small, but notable gap in the data OOI uses to track changes in the marine environment as the planet continues to warm.

"If a [large] institution like WHOI has trouble deploying and keeping these gliders in the water, then how is a smaller institution going to also achieve this goal?" says Reine.

Today, the common glider models retail at around $200,000, which Reine notes may be cost-prohibitive for many universities and marine institutions (at least to buy and service more than one). With fewer gliders in the water, he says the oceanographic community could be missing out on an opportunity to make ocean observations a more global effort.

To overcome these hurdles, he, and a team that includes fellow OOI engineers Brickley and Matthew Palanza, came up with an idea to make a glider that was completely open-source—everything from the vehicle's blueprints to its software, made available to the public on techy, online forums like GitHub. Since 2019, the idea has raised a combined $175,000 of internal funding at WHOI.

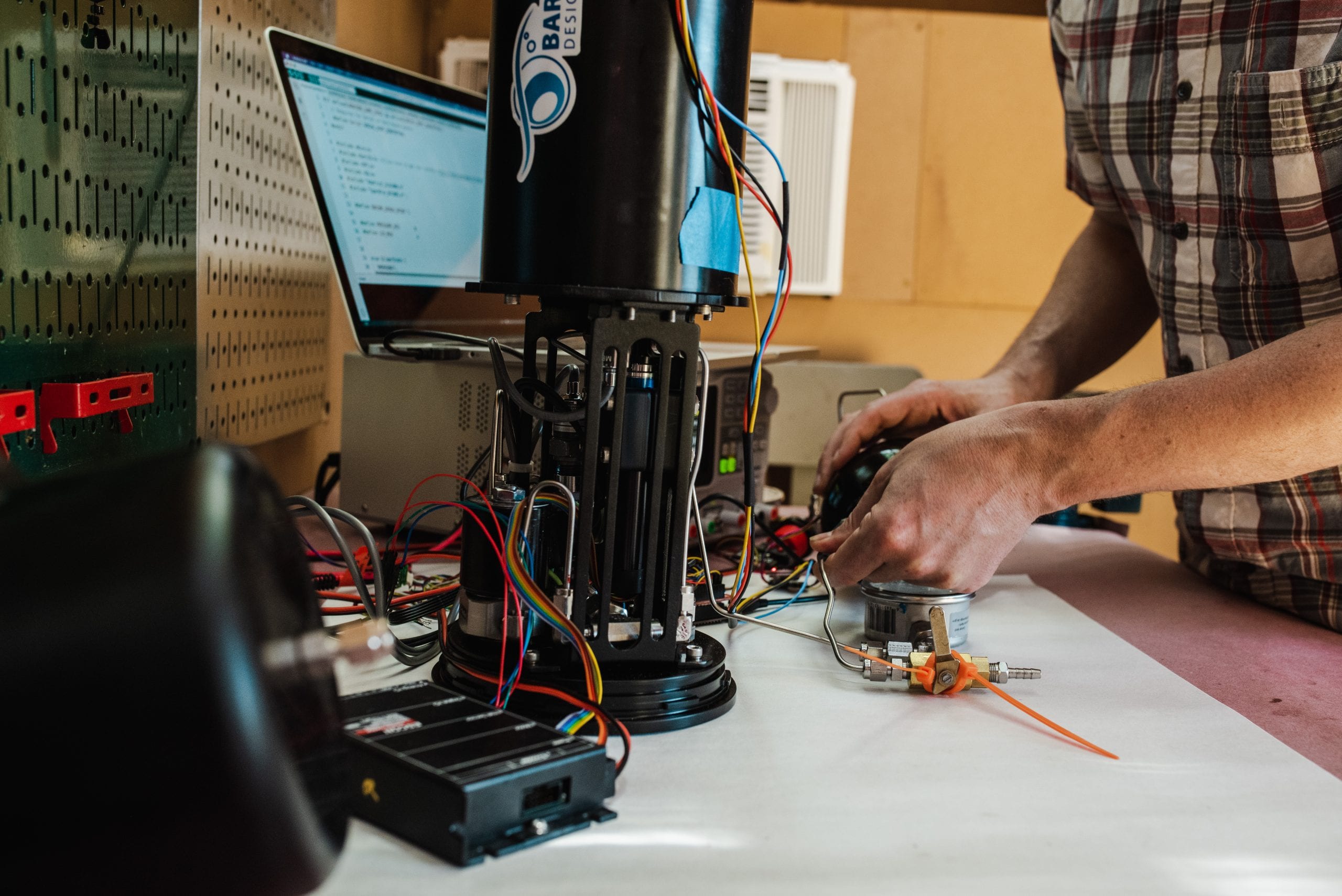

John Reine tests the responsiveness of an open-source buoyancy engine, designed by a former WHOI-engineer Jeremy Paulus, in his shed. (Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Reine and his cohort now meet weekly to shop through a virtual smorgasbord of other open-source and off-the-shelf parts that could be integrated into the design. The current open-source prototype, though not as nimble as other WHOI models, promises to be robust, customizable, and easy to repair, all at nearly a tenth the cost of the more common brand of gliders.

To test how user-friendly the prototype really is, Reine has been presenting some of the open-source components to students at Falmouth High School and teaching them how to program the vehicle. Using the glider's two open-source circuit boards from companies Arduino and Raspberry Pi, students are learning how to make the vehicle's motors turn on and off.

"I want to prepare kids for 'the real world' here," says Falmouth High School's computer science teacher Mike Campbell. "I love having the connection with WHOI, because it lets me know what [technology] is going to be the most purposeful for my students."

In the future, the open-source glider team plans to get the design into the hands of schools and universities with more diverse demographics, in the hope of increasing accessibility to ocean science. From there, Reine and his colleagues say they will encourage other engineers to critique and improve the design, sharing their insights with the community online as they go.

"A diverse user group will continue to improve the device incrementally over time," says Reine's partner, Palanza. "Taking advantage of open source concepts…will empower scientists [and students] to not only build their own equipment locally, but also keep it running."