A Mighty Mysterious Molecule

Chemical compounds are the currency in ocean ecosystems

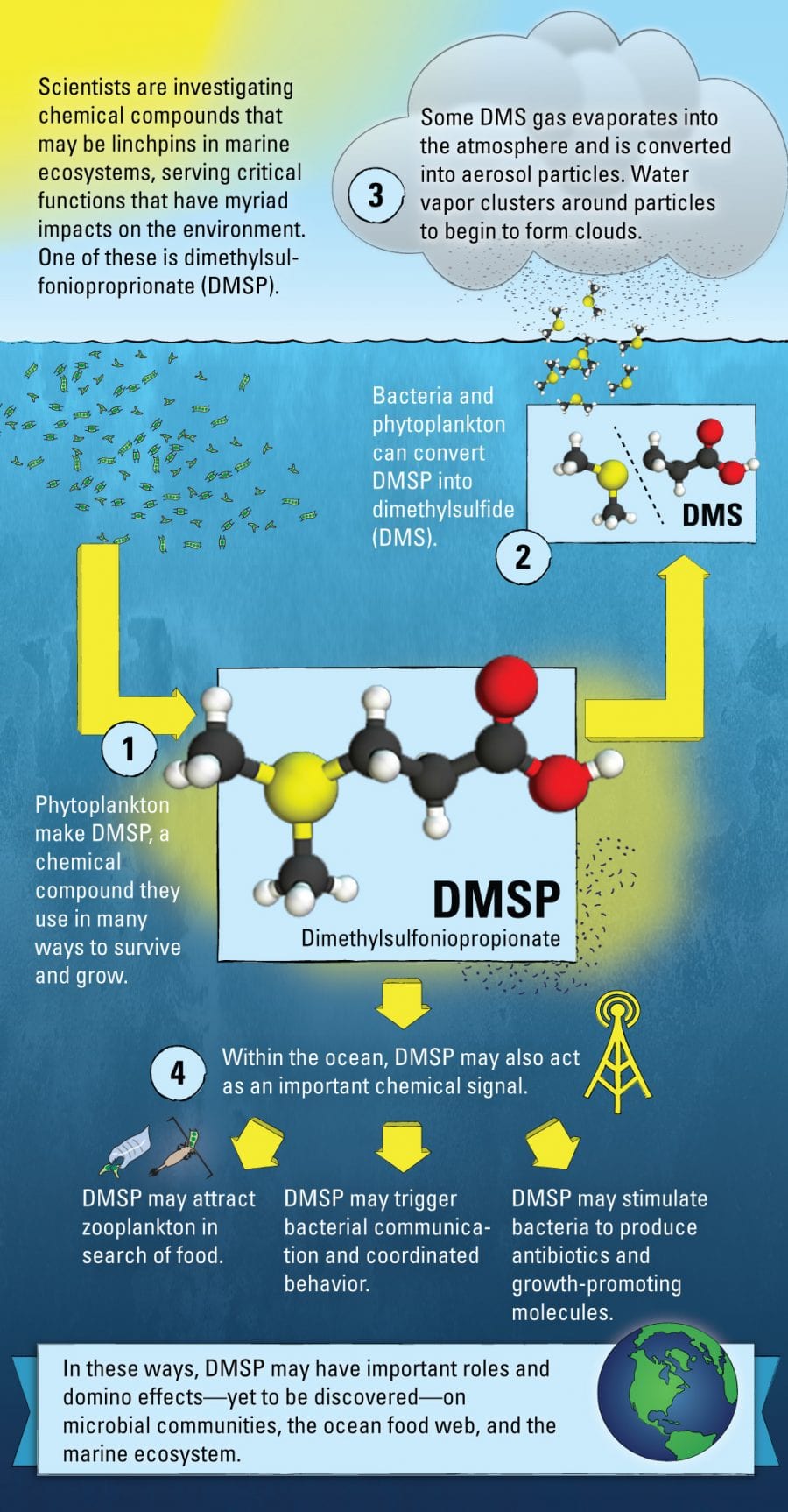

Breathe deeply when you are near the ocean and you’ll pick up the scent of the sea. That vaguely rotten aroma, accented by salt, comes from a molecule called dimethylsulfide, or DMS. But that scent offers only a hint of the fascinating far-reaching roles DMS and its precursor molecule, dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), play in the environment.

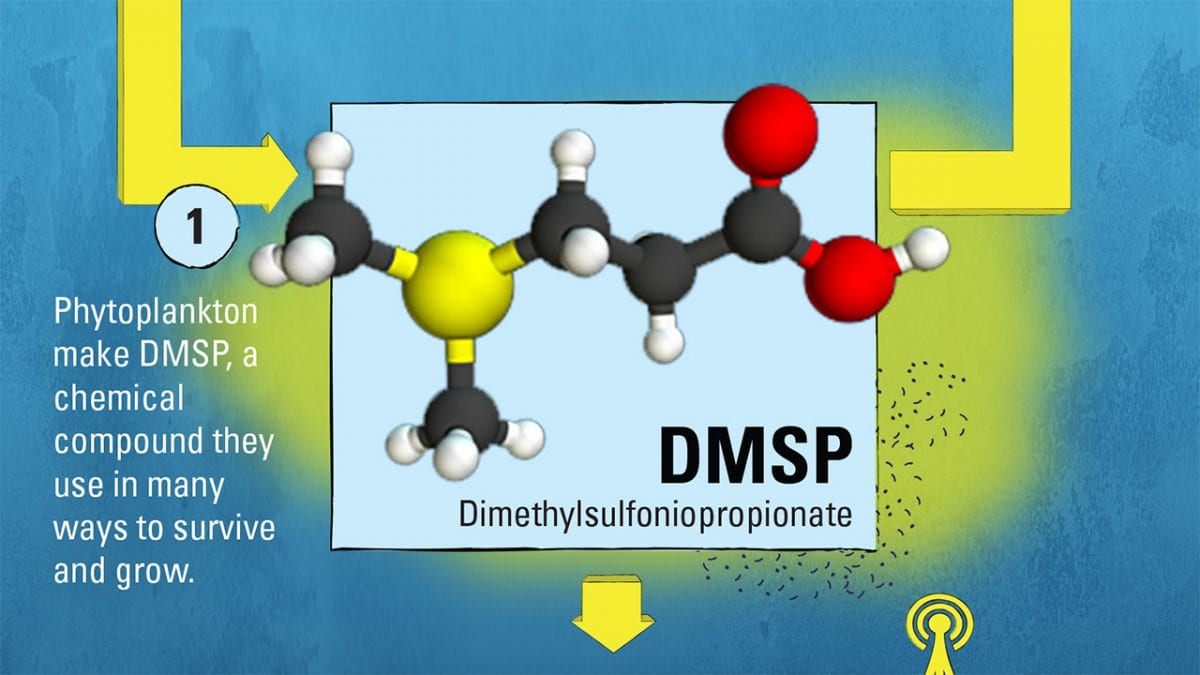

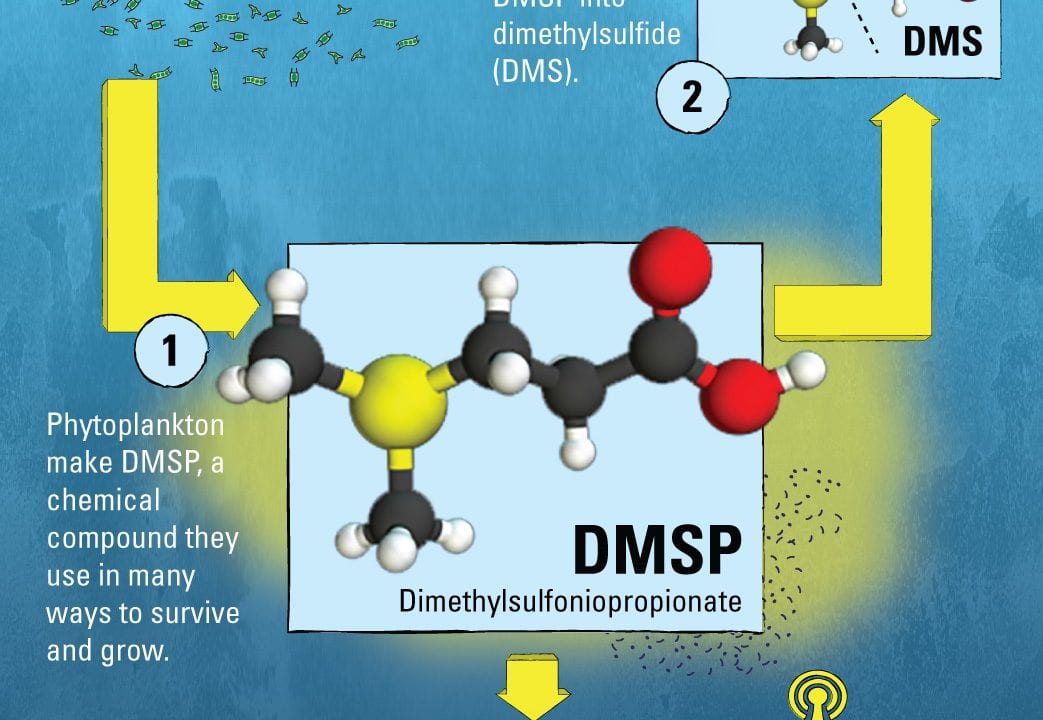

DMSP is synthesized by phytoplankton—the microscopic marine plants at the heart of the ocean food web—for a variety of beneficial uses. Scientists think DMSP acts as an antioxidant to neutralize potentially damaging chemicals generated by cellular processes and ultraviolet radiation from the sun. It may also be used to regulate the pressure inside phytoplankton cells in response to changes in seawater temperature and salinity. In addition, there is evidence that DMSP can function as a chemical signal within the marine food web.

DMSP also serves as food for bacteria that graze on phytoplankton. They can convert DMSP into DMS, the distinctly aromatic gas. When DMS wafts back into the atmosphere, it reacts with oxygen and creates fine aerosol particles. These provide a surface for water molecules to cluster around and begin to form clouds. It has been proposed that organisms can impact the climate around them by producing DMS.

DMSP is only one molecule in the complex mixture of compounds found in the ocean. To really know how the whole marine ecosystem operates, we have to learn more about the molecules that marine organisms produce, respond to, and use. It’s easy to imagine a complex chain reaction where the availability (or non-availability) of DMSP made by phytoplankton would shift the molecules produced by bacteria—which, in turn, would send different chemical ripple effects throughout the food web and the entire environment.

Gaze out at the ocean on a clear day, and it’s easy to forget that within it, a vast number of organisms are going about their lives. I am taking a close look at one of those organisms—Ruegeria pomeroyi, or Rpom, as I affectionately call it—an archetypical bacterium that eats DMSP and produces DMS.

A sea of molecules

The world that Rpom inhabits is difficult for us to imagine. As a bacterium, it is less than a micron in length and experiences forces and turbulence in the water that a larger organism would not experience.

As it is bounced about in this environment, it runs into bits of food. Like us, Rpom is a heterotroph that eats organic molecules to survive. We find those molecules in fruits, vegetables, and meats, but Rpom does not have much control over what it comes across, and so it may grow slowly when there is not much food available.

Occasionally, large particles may drift past. They contain organic matter produced by phytoplankton that use energy from sunlight to turn carbon dioxide into the complex molecules that are necessary for life. These particles are composed of dying phytoplankton, fecal pellets from zooplankton and other animals, and anything else that may stick to them and provide food for Rpom.

Sometimes, Rpom encounters a large phytoplankton bloom upon which it can feast. Relatively large phytoplankton such as diatoms and coccolithophores produce huge amounts of DMSP. Rpom has been found in greater numbers among phytoplankton blooms, suggesting that the phytoplankton provide useful food sources for Rpom, including DMSP.

Relationships between phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria like Rpom are complex and inextricably linked. Experiments have shown that both phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria can change aspects of their metabolism in response to the presence of one another. They can produce higher amounts of molecules such as amino acids or produce compounds that stimulate growth of the other organism.

To explore such relationships, I wanted to investigate how Rpom responds to DMSP, a useful molecule associated with phytoplankton, and enhance our understanding of this molecule’s impact in the ocean.

Window into a molecular world

Organisms make many molecules to build cells and regulate activity inside cells. These molecules, also referred to as metabolites, include the amino acids that form proteins that provide structure to the cell and form enzymes that catalyze reactions in the cell. They also include lipids, which contribute to building the cell wall that holds everything inside. Nucleic acids form DNA and RNA, the blueprints and transcribers/messengers within the cell. Many other small molecules are intermediates in biochemical pathways or send signals within and between cells. With mass spectrometers, we can detect these molecules and see how they change under different conditions.

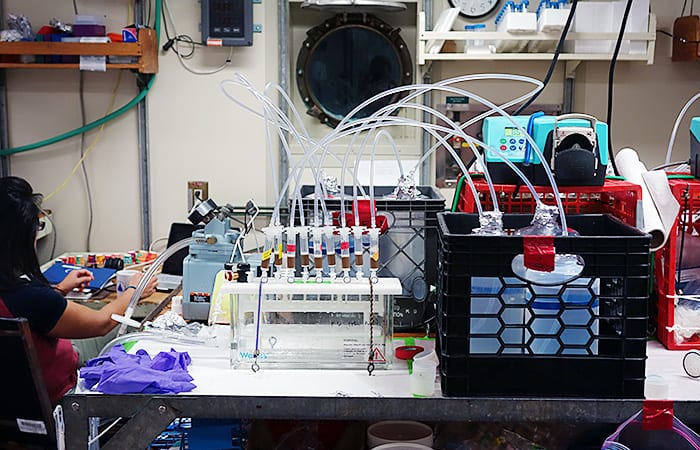

To investigate how Rpom responds to DMSP under controlled conditions, we can grow it in the lab. Then we use two types of mass spectrometers to get a picture of what is happening chemically inside Rpom’s cells.

We use a triple stage quadrupole mass spectrometer to measure metabolites we are looking for. And we use an instrument called a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer, or FT-ICR-MS, to help us discover unexpected and novel molecules. It can detect and measure infinitesimal amounts of individual chemical compounds in a mixture containing tens of thousands of compounds.

In our experiments with Rpom, we grew it with DMSP (C5H10O2S) and, as a comparison, with another molecule called propionate (C3H6O2), which is similar to DMSP but does not contain sulfur. Our mass spectrometer measurements showed that Rpom responds to DMSP as more than just dinner. In fact, we measured higher amounts of a chemical signal that bacteria use to communicate with each other. This type of signal can be used to coordinate behavior among related bacterial cells, stimulating them, for example, to produce antibiotics and form biofilms. So it seems that while Rpom is dining on DMSP, it is also striking up conversations with its neighbors.

While we don’t yet know what they’re talking about, this suggests that DMSP may play a dual role, providing Rpom with information about its environment as well as food. DMSP may have more indirect impacts on the microbial community and organic matter in the ocean that we have yet to discover.

We’re just beginning to gain insights into the variety of organisms in the ocean, the smorgasbord of molecules they are using, and the array of biochemical reactions involved in creating the ocean ecosystem—and of course, the smell of the sea.

This research was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and a National Defense Science and Engineering Fellowship for Winifred Johnson.

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

- For her research, Winn Johnson, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program, collects seawater samples. In a shipboard lab, she filters the seawater through a polymer/resin with a vacuum to extract metabolites dissolved in the seawater. Back on shore, she uses mass spectrometers to detect and measure tiny amounts of individual chemical compounds in a mixture containing tens of thousands of them. (Winifred Johnson, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Evidence for quorum sensing and differential metabolite production by a marine bacterium in response to DMSP Article by Johnson, Soule, Kujawinski in The ISME Journal (the multidisciplinary journal of microbial ecology)

- Elizabeth Kujawinski's Lab