Three questions with Carl Hartsfield

Captain Hartsfield, USN retired, discusses the role ocean science plays in our national defense

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

Q. With so many discoveries emerging from the oceanographic research we do, how do we determine which findings may have implications for national security?

Any time you discover a new phenomenon in the ocean, whether it be some type of duct or temperature gradient, it can have national security implications. We know this from WHOI’s rich history of converting knowledge about the ocean into military advantage. A prime historical example of this relates to something called the “afternoon effect”—a phrase used to describe the difficulty of detecting submarines during calm, sunny days. Back in the early 1930s, no one understood what caused this. So, researchers at WHOI began looking into it and, through a mix of science, acoustics, and instruments like the bathythermograph, were able to solve the mystery. They determined that warm surface water in the afternoon can cause “sound ducting,” whereby the ocean layers in density and bends sound waves downward. This traps sound within the layer and prevents it from traveling deeper.

Fast forward to now, and submarines routinely use layers, sound ducts, eddies, ocean currents, ice melting, and other ocean phenomena to amplify detections and hide on the other sides of barriers. We call it “tactical oceanography” in the submarine force today. Science, technology, and the military all invested their genius to better understand the ocean and use that knowledge to strengthen our national defense.

Q. Open science emphasizes transparency and sharing discoveries, which at times must conflict with the secrecy required for national security. How does WHOI balance these competing priorities?

First, you have to be a master of the information and understand when you can share information and when you can’t. That requires a great deal of experience. Over decades of working with the military, WHOI has been able to effectively distinguish between the scientific realm and the national defense realm and toggle between the two. We know that a lot of the basic science we do can be readily shared among the public, but when some of these non-tactical discoveries we make in the ocean have tactical applications, things tend to get classified quickly.

In general, it’s always a very delicate balance when it comes to scientific discovery and national security, and we need our folks to know where the lines are drawn.

Q. What do you see as the biggest growth area for WHOI in national defense?

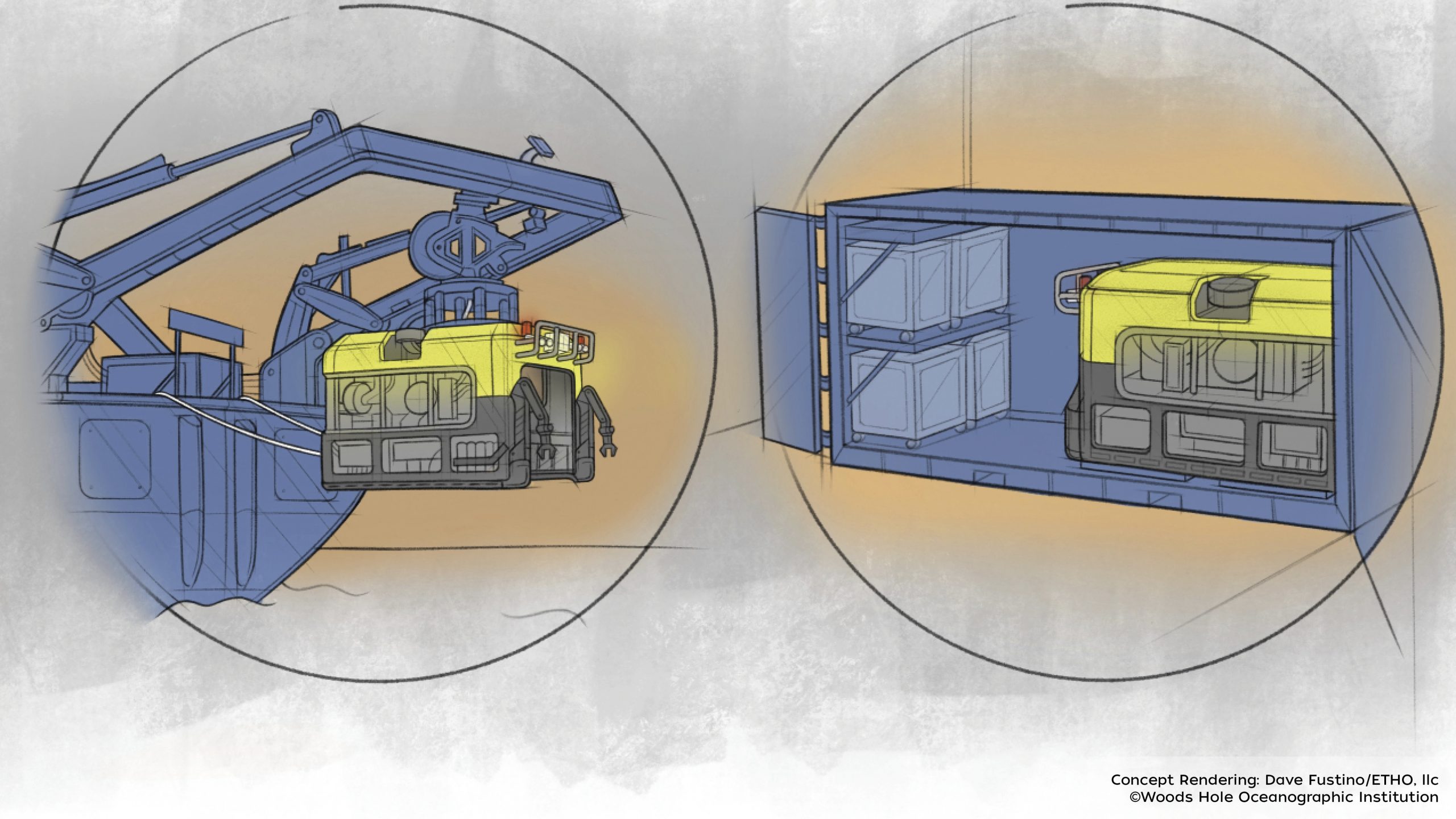

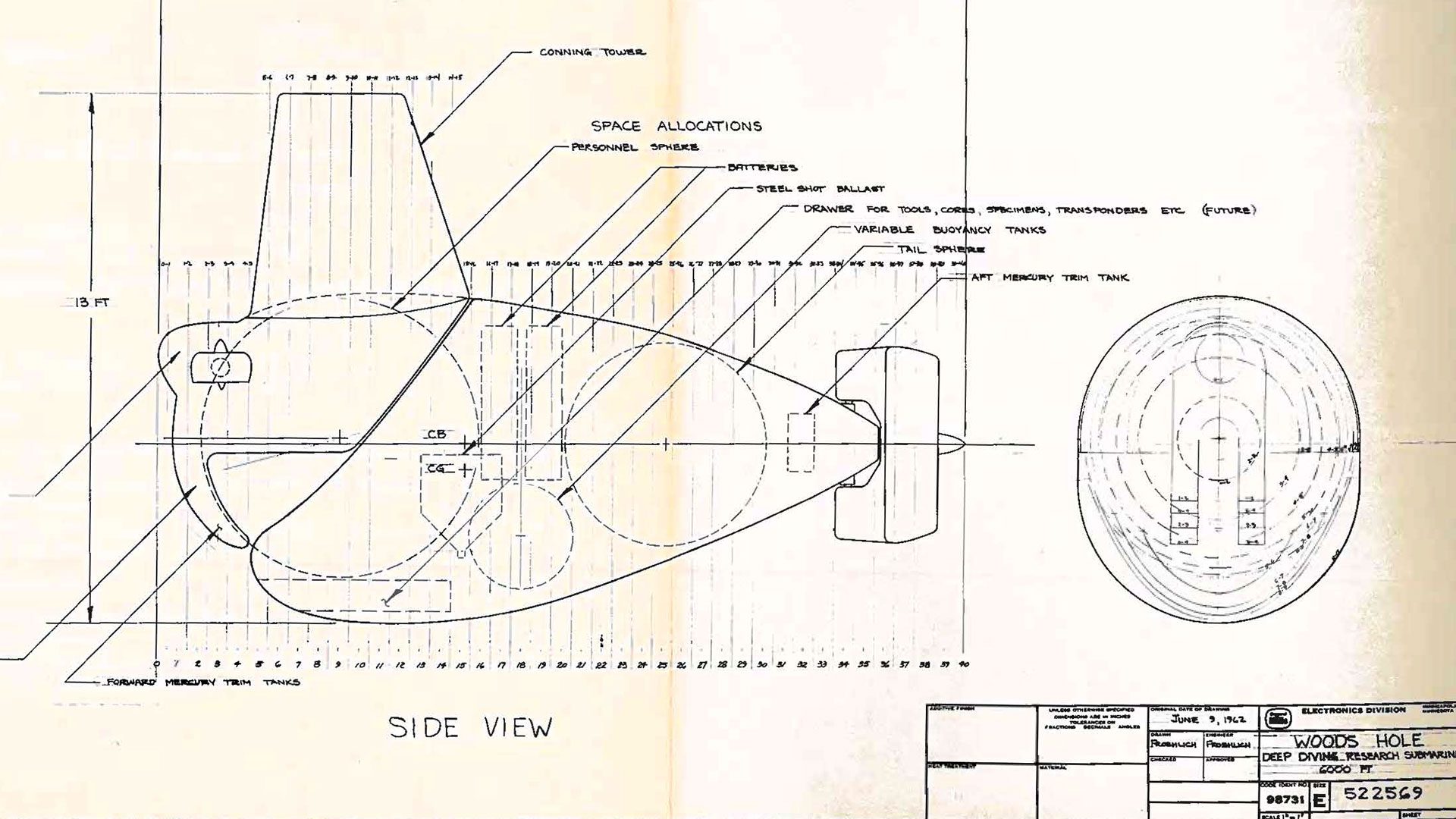

One of the big areas the Navy wants to invest in is equipping submarines and other crewed military assets with uncrewed vehicles like REMUS AUVs. Here at WHOI, we do this every day with the Armstrong, the Atlantis, and other research ships. We mix these crewed vessels with ocean robots and other uncrewed vehicles, which significantly expands the scope of what we can explore, measure, and observe in the ocean. It extends our reach.

Well, the same concept applies to submarines—the Navy wants these very expensive assets, which can cost $3 billion or more, to have more capability and increase the scope of what they can do. They want to increase the return on their capital investments.

Toward this end, our engineering team at WHOI figured out a way to turn a submarine torpedo tube into a launching and docking port for REMUS vehicles. Our first demonstration of this capability was with the Yellow Moray (REMUS 600), which can autonomously launch out of the tube, go away from the submarine to perform a task, then return and autonomously dock itself back into the tube almost like magic. The AI-enhanced software to dock took nearly a quarter-million lines of code!

The problem we’ve solved with the Yellow Moray project is a really hard one; the Navy tried to do it for many years. In achieving this, WHOI has been able to add capability to submarines that multiply the force, building more value per dollar per unit. These uncrewed vehicles can also lower the risk to humans since each can autonomously handle tasks that would otherwise put crew in danger. By design, our efforts significantly reduced the number of crew members onboard needed to manage these REMUS AUVs during missions. More capability, less risk, and less burden on the crew—it has been a real game-changer for the Navy.