Rising tides, resilient spirits

As surrounding seas surge, a coastal village prepares for what lies ahead

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2025

Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

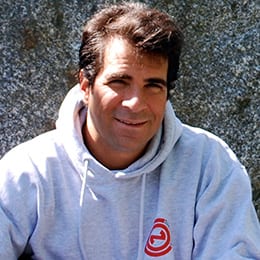

On Sunday afternoon, Jim Estes watched as a river of kitchen paraphernalia—utensils, pans, beverage containers—floated out of his restaurant and into the parking lot. It was an early sign, he feared, of what was to come.

The night before, Aug. 18, 1991, gaggles of patrons, some of whom were in Woods Hole to run the seven-mile Falmouth Road Race, huddled around the lively bar inside Landfall, Estes’ weather-shingled restaurant, for a night of spirits, seafood, and story. With its salty vibe and expansive, open-air dining room perched just inches above the ocean’s surface, Landfall was the de facto community gathering spot in Woods Hole.

As laughter erupted from the standing-room-only crowd and servers buzzed the dining room with plates piled high with fried clams, no one seemed too concerned about what was happening 700 miles (1126 kilometers) south near the Outer Banks of North Carolina. But that’s where the real action was. A Category 3 hurricane, named Bob, was picking up strength.

Jim Estes, co-owner of Landfall, looks out at the Atlantic Ocean just off his restaurant’s dock. (Photo by Daniel Hentz, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Several days earlier, two air masses south of Bermuda had collided during a front, forming a pocket of low pressure. As the depression circulated, it muscled into a tropical storm near the central Bahamas, where it began slurping up heat from the Gulf Stream. Then, it throttled northward toward New England.

Back at Landfall that night, after the last guests headed home, Estes locked up the restaurant. Rather than driving home, he decided to crash in a makeshift apartment next door in case the seas became sporty.

When he woke up Sunday morning, the wind was slowly picking up under a ghostly gray sky. By afternoon, the Steamship Authority’s parking lot next door looked like a swimming pool.

Hurricane Bob, Estes realized, had come knocking.

“It was clear we had a hurricane on our doorstep,” Estes recalled. “We immediately started getting everything 4 feet off the floor and removed all the French doors along the deck for safe keeping. It was all-hands-on deck.”

Within a few hours, everything was off the floor—at least what was left of it. The storm surge had barreled into an algae-coated stone seawall running beneath the piled building, causing geysers of seawater to rush up against the wooden floor from below until large sections buckled from the pressure.

“Seeing the floor damage was a low point,” Estes recalled. He knew Landfall would have to shut down for a while, which in turn meant that his staff would end up losing a lot of pay. “As a restaurant owner, it weighs heavy,” he said.

The walls and roof, however, survived. It turns out that the original structure, built in the early 1940s, had been designed so that the wooden piles supporting the walls and roof were kept independent of those anchoring the floor. And the restaurant was built with a feature that Estes calls “the flap”—a rectangular wooden panel hinged to the outside rear wall. It opens like a huge mail slot to allow storm surge to flow through the restaurant versus battering against it.

“All you can hope for is for the ocean to flow through and back out, and hopefully not take much with it,” Estes said.

On the edge

In the 1940s, no one knew that Landfall’s original collapse-resistant structure or the “flap” would become emblematic of a broader resiliency planning initiative, known as ResilientWoodsHole (RWH), a private-public collaboration aimed at increasing climate resilience in Woods Hole.

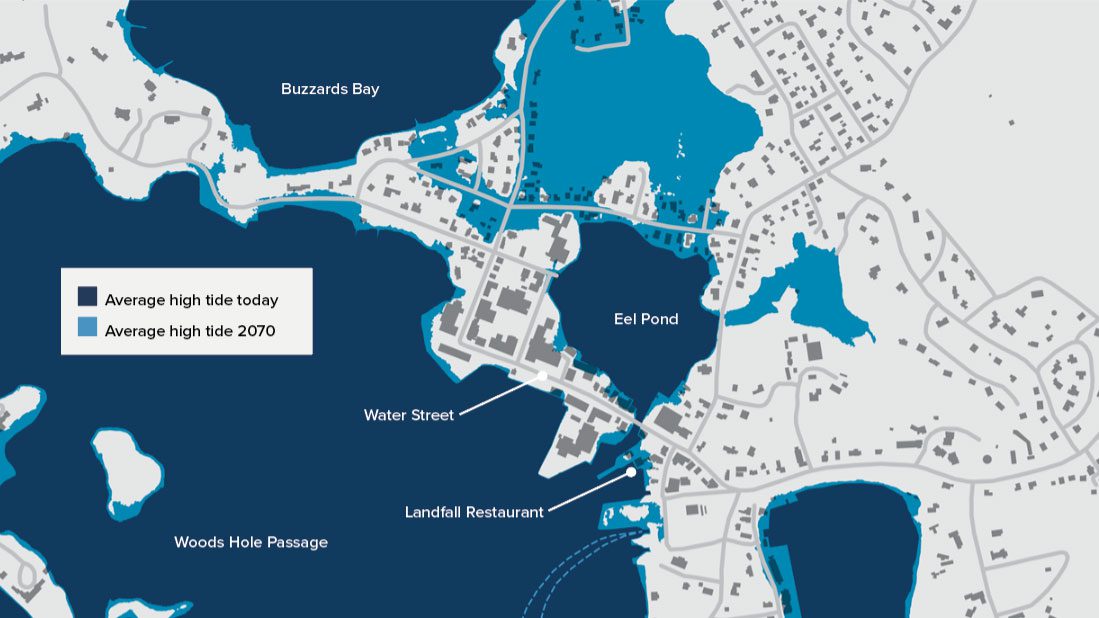

The picturesque coastal village, which is dotted with vibrant shops and restaurants, residential homes, museums and libraries, and three major oceanographic institutions, has experienced frequent coastal flooding in recent years, and the trend is expected to accelerate. According to analysis conducted by the environmental engineering firm Woods Hole Group, by 2070, one-third of the roads in Woods Hole could become inundated during storms, putting nearly $300 million in property at risk.

Landfall is particularly exposed to flooding since it sits directly above the Atlantic Ocean. But according to Irina Polunina-Proulx, a project coordinator for RWH, it’s not hard to find other vulnerable spots throughout Woods Hole.

“At Waterfront Park, which is owned by Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), if there is a combination of high tides, strong winds, particularly coming from the southeast, and an associated storm, the waves and their spray can overtop the seawall, as we saw in December 2023,” she said. “If the waves are large enough, water can begin to accumulate on Water Street and can flood some of the MBL docks.”

There’s also the boiler room in WHOI’s Bigelow Laboratory, where water often accumulates during storms, the abandoned tennis courts adjacent to Stony Beach, which regularly become inundated since the dunes that had once protected them have washed away, and the ballpark off Bell Town Lane, which fills up with so much water during storms that residents drag their kayaks out and leave their baseball bats at home.

To understand how things got to this point, you first need to look back to the last glacial maximum nearly 20,000 years ago when much of the continental shelf to the south of Cape Cod was dry land on which mastodons and mammoths roamed. During that period, the ice sheet covering much of North America, which deposited the sediment that forms the backbone of the Cape, was a few kilometers thick—heavy enough to depress the Earth’s crust below and push mantle materials out to the side. This created what is known as peripheral bulges around the ice. Eventually, the ice sheet melted, but the bulged-up crust and mantle are still “relaxing,” according to WHOI geologist Jeff Donnelly.

“Right now, we’re sinking relative to the sea as the mantle material beneath us continues to move back to Canada. The seas are rising, but land is also subsiding on top of that,” he said.

When adding that to accelerated climate change, higher intensity storms, and continued glacial melt, it is not hard to see why Woods Hole is in a particularly tough spot.

Raising Water Street

From Leslie-Ann McGee’s office window above Water Street, you can see a white PVC pole mounted atop one of several crooked, weather-beaten pilings that support Iselin Dock on Woods Hole’s sprawling waterfront. There’s nothing fancy about the pole, and most people likely don’t notice it as they walk by. But the silent sentinel—a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) tide gauge—began tracking water levels there in 1932. Since then, it has recorded more than a foot of sea level rise.

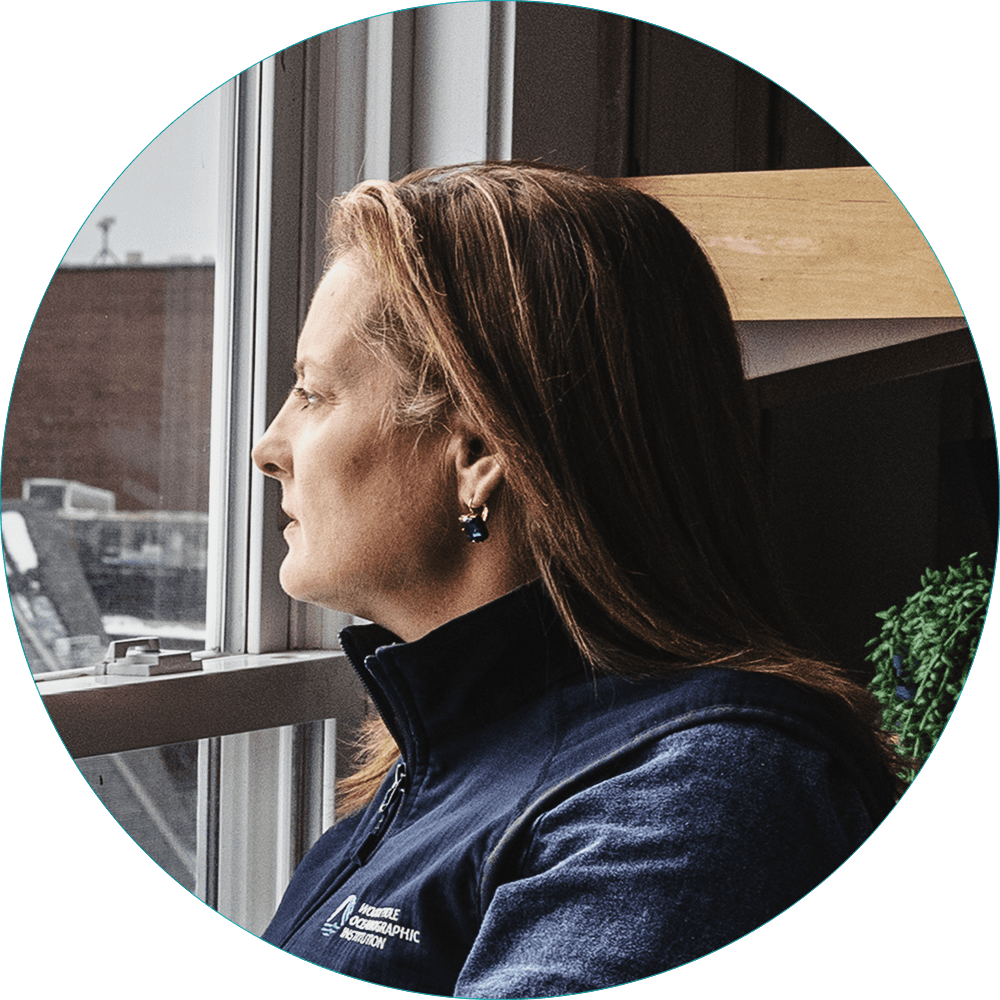

McGee is the chief innovation officer at WHOI and managing director of RWH. Back in 2019, the institution had grown concerned about the potential impacts of rising seas and storm surge on its waterfront facilities.

“At the most basic level, we are a seagoing organization,” she said. “Having a waterfront facility that can stand the test of time, resilient in the face of what we know is already coming at us, is the most fundamental aspect of our organization in terms of empowering access to the sea.”

She and her colleagues began collaborating with researchers and facilities managers from the neighboring Marine Biological Laboratory and NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC), looking at the critical elevations for their respective buildings and how they could be impacted based on sea level rise predictions.

“We realized this information needed to get into the community so people could plan for their own properties and businesses.”

—Leslie-Ann McGee, chief innovation officer at WHOI and managing director of RWH

“We realized that we couldn’t just sit there admiring the problem—we needed an action plan,” she said.

They came up with an ambitious one, which McGee refers to as the 2030 Centennial Vision: raising buildings along Water Street from their current elevation of 6.5 feet to 14 feet (1.9-4.2 meters) above sea level and rebuilding the dock with a new pier system and dependent high bays that are 2.5 feet (.75 meters) higher than they are today.

As the team began laying the groundwork with town officials for the multiphase project, they realized that much of the data they had amassed from the vulnerability assessments was data they could not keep to themselves.

“We realized this information needed to get into the community so people could plan for their own properties and businesses,” McGee said. “That’s how ResilientWoodsHole was born.”

The program, which was launched in 2019, has been working to assess threats and develop solutions jointly with residents, town officials, and other stakeholders. Assessments are made with what’s known as the Massachusetts Coastal Flood Risk Model, a computer model that simulates flooding scenarios from storms and sea level rise. It’s based largely on decades of modeling work that Jeff Donnelly’s lab has done in conjunction with Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

“About 15 years ago, Phil Lane, one of my students in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program,

came up with an innovative way to couple inundation modeling with individual hurricanes that allowed us to get reliable statistics on not only hurricane tracks and landfall, but the inundation itself,” Donnelly said. “The flood risk model the state is currently using for sea level rise projections ties back to that earlier work.”

Modeling technology will continue to be crucial in helping improve sea level rise predictions. But advances in sensor development, too, will play an important role since direct observational data are needed to ground truth inundation models and make them more precise. WHOI research associate Levi Gorrell, along with WHOI associate scientists Sarah Das and Chris Piecuch, recently codeveloped a low-cost water level sensor that will help fill long-standing gaps in sea level data, initially across Massachusetts. According to Piecuch, WHOI’s proximity to the coast served as easy inspiration for the project.

“This isn’t astrophysics, where the science you're doing is somewhere out in the distant universe. We live and work by the sea,” he said. “Being on the Cape where we’re able to see the impacts, it’s really incumbent on a place like WHOI to do this kind of work.”

The floodplain whisperer

Pam Harvey, a lifetime summer Woods Hole resident and member of the RWH Steering Committee, said that what sets RWH apart from resiliency programs in large cities is the more granular, grassroots approach to helping the community protect against current threats.

“It’s based more on what residents here need,” said Harvey, who is no stranger to the impacts of climate. She grew up hearing stories about how her own grandparents’ house in Woods Hole moved about 30 feet (nine meters) during the 1938 New England Hurricane.

Part of that granular approach is providing personalized, one-on-one guidance for residents on steps they can take to mitigate impacts. According to Shannon Hulst, a guest investigator at WHOI, most people in Woods Hole don’t want to elevate their homes. However, she said, “there are often things they can do right now to protect their homes and stay safe.”

Hulst meets regularly with residents in Woods Hole and the broader Cape Cod region to discuss specific actions they can take based on their property’s flood plain and projections for sea level rise.

Common actions include installing flood vents in crawl spaces to allow water to come into the space without cracking foundations, and putting up deployable flood barriers against their homes to keep water out, she said. “In other cases, I might recommend filling in your basement with pea stone, or elevating appliances like hot water heaters and furnaces.”

Rising seas, rising floors

At Landfall, the Estes family has been consulted on adaptation strategies as well—long before “climate resilience” became a household term. In 1991, after Hurricane Bob struck, Jim and his brothers Bill and Don, who were part owners at the time, called Walter Yorish, a local architect, to see if he could design a new floor system that would hold up to future storms and not buckle when inundated. He came up with a simple, yet elegant solution: removable, hatch-like floor panels that could be built into the new dining room floor and removed to release the water pressure when a storm barrels in.

“The goal was to eliminate the resistance to the flow of water,” Yorish said. “By removing the panels and allowing the water to flow up and out, it prevents the floor from lifting up and becoming damaged.”

Today, if you look closely enough, you can make out the removable floor panels in the dining room—each is bordered by a frame of 4x4 planks. Fortunately, they have stood the test of time—Landfall has not experienced floor buckling or damage since Hurricane Bob. It’s a design strategy that, along with the side-panel “flap” at the back of the restaurant, keeps water moving through the building and out when the sea is surging.

“In a way, the hurricane turned out to be a benefit in the end—it allowed us to design a better, more resilient restaurant,” Estes said.

Anxiety into action

Still, for the Estes, the nagging threat of storm surge is a constant source of worry—one that has run through their family’s veins since they were kids.

“Every summer from 13 years old on, we dish washed here, fry cooked, broiler cooked, and bartended,” said Estes. “We always heard the stories and were taught about hurricane prep—what to look for, what to do when a storm comes through. It was always on our minds, and it still very much is.”

Longtime residents are feeling it, too. Edith Clowes, whose family has owned the same waterfront property along Nobska Beach since 1926, describes her house as “very exposed” and said that last year, the property experienced four major flooding events. During one storm, she looked out her living room window and saw swans swimming in her front yard. As beautiful as they were, their presence underscored the uncertainty about her home’s future.

“It’s deeply anxiety-arousing,” she said. “My family members and I are worried about the longevity of the house—in 50 years, will those generations of the family be able to hold onto the house? Will it go under the waves?”

Clowes said she and her family are trying to channel their own climate anxiety into action.

“Next weekend, we’re having a whole family Zoom meeting on next steps,” she said. “We’re not sure our house will survive, but it’s my heart’s home. So, we need a game plan.”

Staying put

At Landfall, the Estes family has a game plan too. But for now, it doesn’t include making additional modifications to the building or moving the business to higher ground. Their only plan right now is to extend the restaurant’s legacy by keeping it in the family. They know that, even when the seas are acting up outside, very few eating establishments on Cape Cod offer the same type of immersive front row seat to the Atlantic.

“When you have 35-mile-per-hour winds coming out of the south-southwest and waves are rolling up against the dock, it may not be all that pleasant outside,” Estes said. “But just on the other side of the glass, there’s a candle, two glasses of wine, and a husband and wife enjoying a nice soft dinner. That in itself is pretty amazing.”