When we pull out a world map, details sprawl across the continents, highlighting the intricate features of the terrestrial world. In between these places we call home, a simple blanket of blue fills in the rest, as if the details didn’t matter.

In 1942, Athelstan Spilhaus, a South African-born geophysicist, oceanographer, and inventor at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, saw that blue void as more than just filler. He had a bold idea: What if we drew the map with the ocean at its center? After all, despite its misleading name, Earth is an ocean world.

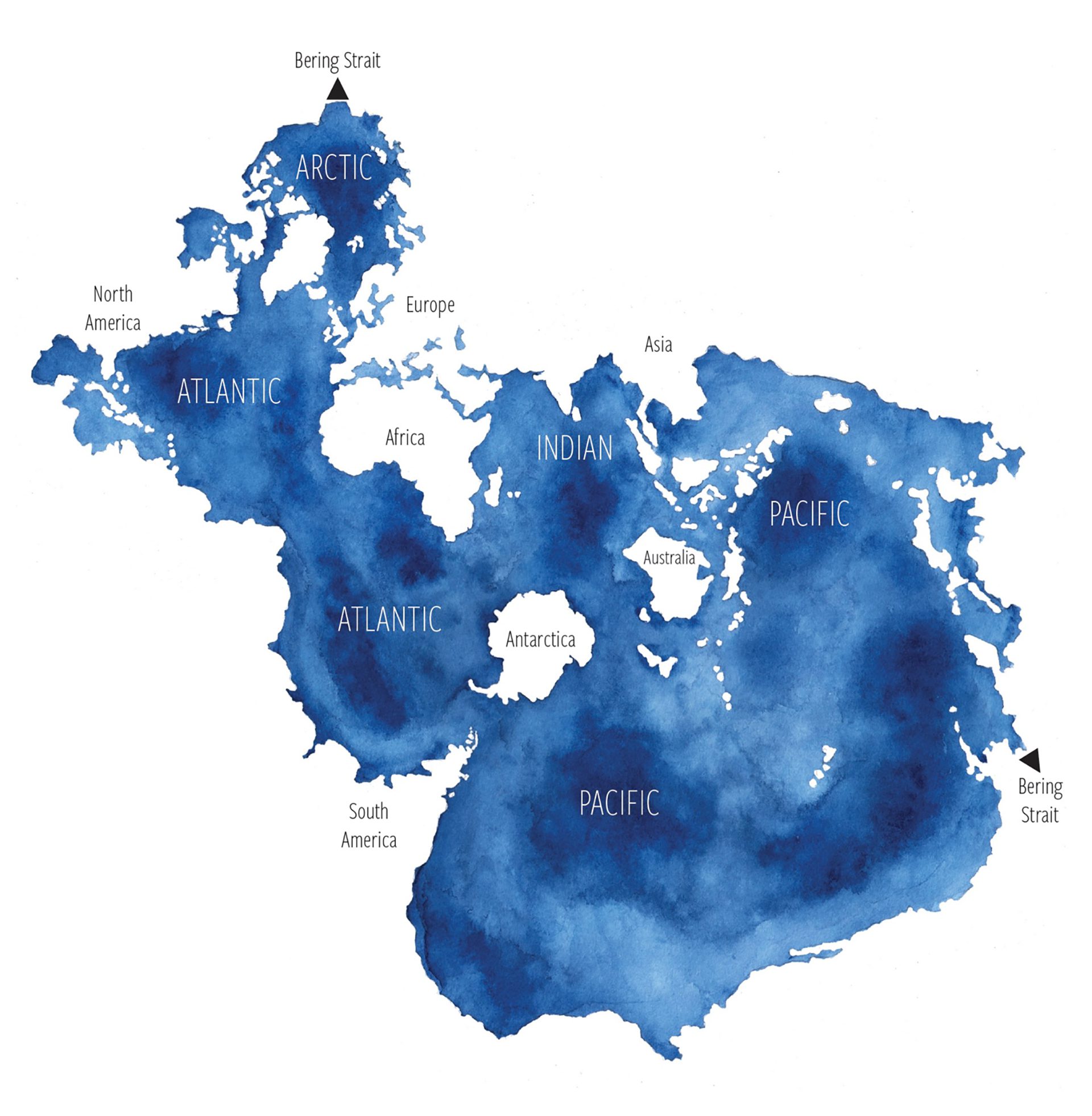

Spilhaus believed this map would be more accurate and honest if it weren’t based on a worldview centered around England (where most 20th-century cartographers lived), and spent his career crafting what’s now known as the Spilhaus projection. Using continental shorelines as "natural boundaries," this projection depicts the ocean as one interconnected waterbody with a minimal amount of distortion. This perspective emphasizes the global circulation of currents, the interconnectedness of marine ecosystems, and the shared nature of the world’s ocean—concepts that are fundamental to oceanography, climate science, and Earth system studies today.

To reach this revelation, Spilhaus traveled across well-defined land maps and into the unknown blanket of blue. At age fifteen, he was admitted to the University of Cape Town, which led to a summer job as an apprentice engineer on a cargo vessel and a volunteer position in a German aircraft factory. From there, he went on to study aerodynamics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he enrolled in the MIT-WHOI joint program for graduate studies. With guidance from Carl Rossby, a meteorologist at WHOI, Spilhaus developed the bathythermograph, which revolutionized how oceanographers and biologists study ocean temperature at depth. This invention, which aided the U.S. Navy’s submarine strategy during World War II, was just the beginning of his many contributions to the emerging field of oceanography.

Spilhaus’s career took him in many directions, from assistant professor at New York University and summer positions at WHOI to operating weather stations from behind Japanese lines as a temporary officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps during WWII. After the war, Spilhaus became the director of research at NYU for two years before serving as the dean of the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Technology, a role he held for 18 years. During this time, he developed his forward-looking designs and philosophies, including the idea of covered skyways and tunnels connecting city buildings. He was appointed the first U.S. representative to UNESCO and founded the Sea Grant College Program, while also advising Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson on matters that connected science, education, and policy. Over the course of his career, Spilhaus wrote 11 books, published more than 300 scientific articles, and is credited with many inventions.

Athelstan Spilhaus spent his life redefining boundaries on maps, technological possibilities, and how people imagined the future. Whether gazing across the ocean or into outer space, he saw connection where others saw separation, and possibility where others saw limits. His ocean-centered map was a metaphor for his worldview: that humanity’s understanding of the planet must begin with the sea. From the depths of the ocean to the edge of the atmosphere, Spilhaus and his World Ocean Map Projection helps us see Earth as it truly is: one interconnected system, bound together by water, science, and imagination.