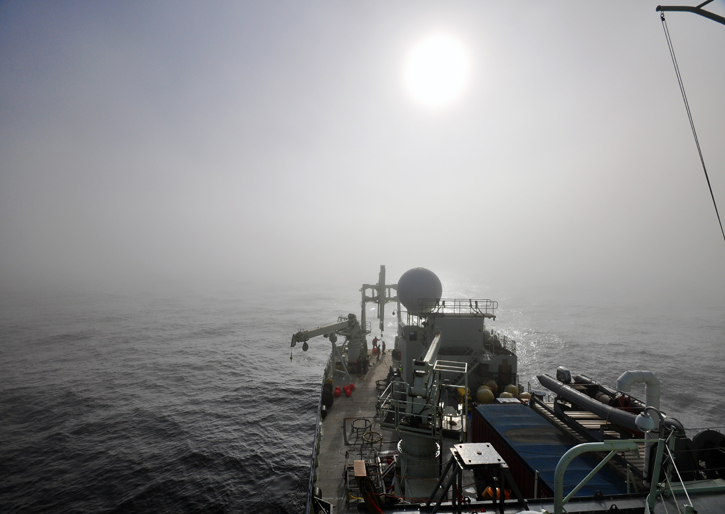

August 26, 2011Conditions today are decidedly different from yesterday, alas. Visibility has shrunk to barely a ship’s length in leaden fog with a bone-white glow where the sun is supposed to be. Again, the shipboard mood matches the weather, only in the opposite way from yesterday. People are going about their work as usual but with a quiet and subdued aspect, speaking softly. I hear little laughter or frivolity this morning. Moderate wind from the southwest sets Knorr to rolling languidly, a motion that seems also to match today’s mood.

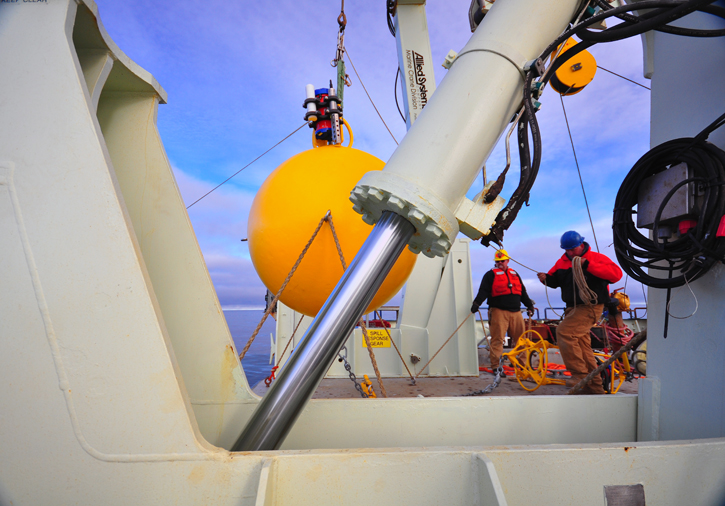

Fog moves in and chills the air. © Rachel Fletcher Watching the mooring operations, I was thinking about the unique combination of heavy industry, advanced science, and sophisticated electronics that characterizes at-sea oceanography. If you venture aft onto the transom while they’re laying moorings without a hardhat and life vest, Kyle the bosun will peer at you over his sunglasses, tap his head, and point forward. This regulation is inviolate for good reason. Cranes are swinging very heavy objects overhead, lines and wires are stretched under load, heavy-duty winches are turning, and there’s always something behind you to fall over. And that’s in fine weather. Add a pitching deck when big seas are running under her stern and the jeopardy level, not to mention the requisite skill level, soars.

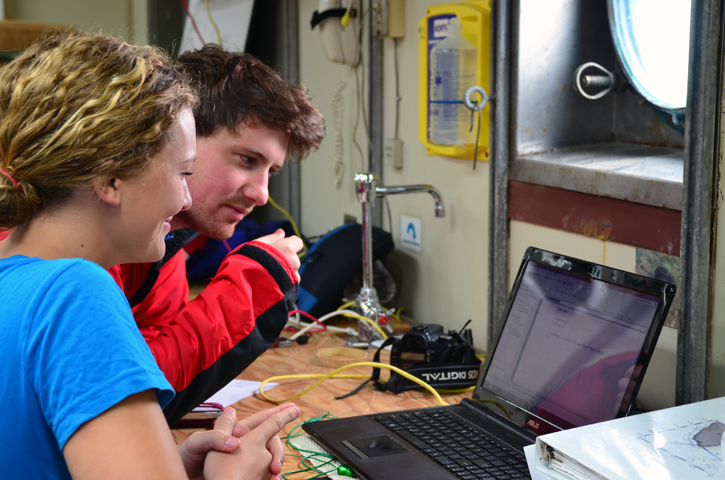

Then you come off the deck into the main lab and there’s Bob (U.S.), Kjetil (Norway), Laura (Netherlands), and Hedinn (Iceland), all four of them world-class scientists, analyzing fresh data, composing cross-section profiles of the local ocean using special-purpose computer programs while surrounded by esoteric, fine-tolerance measuring devices lashed to the tables and floor waiting to go overboard. All four have contributed moorings (and brain power) to the project, but Laura and Hedinn will leave the ship next week when mooring ops are complete. Then Bob and Kjetil will lead the exploring expedition in search of the headwaters of the North Icelandic Jet, requiring the quick and nimble analysis of real time data to decide where to go next, an atypical sort of oceanography. They’re all working now at their computers in what we call a lab, but this is not the sort of white-coated, controlled-conditions work evoked by the word “laboratory.” This one moves constantly. (All our computers are lashed to the desks; sometimes you need to hold on with one hand and type with the other.) All work is conducted only at the behest of the wind.

Kyle, the Bosun, keeps watch over the deck. © Rachel Fletcher You can always tell which scientist’s mooring is going in the water and when. They are all normally open, funny, and relaxed, but not when their mooring is being assembled and deployed. Then, clipboard in hand, they walk from the lab to the deck and back with head-down determination, tense, lost in abstracted concentration. They know consciously and appreciate that they’re in the best of hands with John Kemp and Jim Ryder handling their equipment, but it doesn’t matter. This is a big thing for them. They’ve purchased the mooring components with grant money from the National Science Foundation or its European equivalent and shipped the stuff to Iceland from their respective institutions where it was loaded aboard Knorr. But have they forgotten anything? Have things been lost in transit? Is everything working? Will the acoustic releases actually release? But there’s more to it than just the equipment.

Hedinn Valdimarsson, Bob Pickart, Laura de Steur, Kjetil Våge. © Rachel Fletcher There’s the data. They’ve planned at least part of their immediate futures around its retrieval and analysis. The data is the lynchpin often of a long, on-going project. They’re planning to write and publish papers that depend on the ocean data the moorings and the other devices are meant to collect. The data is more valuable than the instruments. But there wouldn’t be any data, there wouldn’t be any physical oceanography without this ship. We’ll talk as the days go by about Knorr and the various shipboard departments (engineering, galley, deck, and bridge). But for now, we need to credit the unity formed by the technicians, the scientists, the Knorr and her complement. Absent one, the others couldn’t succeed. I can wax all runny and romantic about this ship and the people who operate her, but I’ll spare you that. However, if a visitor from off the street came aboard for a week and observed the entire operation, the unity, he/she could be excused for thinking that, well, yeah, there’s a lot of stuff going on, but all in all it’s pretty easy. That would be because all three components of the unity make the complex, difficult, physically and intellectually demanding work look easy.

Techs maneuver the large float, complete with attached ADCP, on the aft deck. © Rachel Fletcher Tomorrow, word is, we’ll come close aboard the east coast of Greenland at about 68° North. It is the most spectacular coastline this side of Antarctica, as the photographs will illustrate—if the fog lifts. If it doesn’t you’ll have to take my word for it. Or not.

Ben Harden & Kate Lewis. © Rachel Fletcher Last updated: December 27, 2011 | ||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | ||||||||||||