Woman on Board

A conversation with WHOI mooring technician Meghan Donohue

Meghan Donohue wanted a career in oceanography.

She earned an undergraduate degree in physical oceanography from the University of San Diego. Then she participated in a semester aboard the Sea Education Association’s ship, where she discovered that what she loved most was working on deck, handling the ship’s rigging and equipment.

Donohue went on to get a mate’s license and graduate from Maine Maritime Academy. She took a position as a shipboard technician at Scripps Institution of Oceanography—still thinking she would eventually pursue a doctorate in oceanography. But the more time she spent working on ships, Donohue said, the more she realized she did not want to become a scientist.

“I just loved doing field work and being out at sea, and being able to facilitate scientists getting their data.”

By chance, she ended up on a research cruise with John Kemp, head of the Mooring Operations and Engineering Group at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), who offered her a job in August 2014.

“I got lucky and was able to move cross-country to come work for WHOI, doing what I like to do,” she said. But by choosing a job done by few women, she knew there would be challenges.

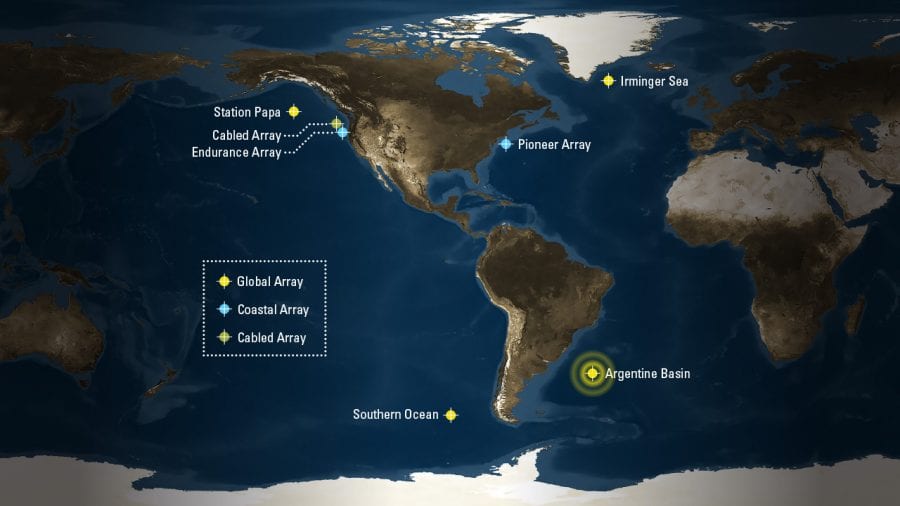

I talked with Donohue in October 2016, as she headed out to sea on a monthlong mission aboard the research vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer to service the Ocean Observatories Initiative’s Global Argentine Basin Array, a set of deep-water scientific moorings that collect data on ocean conditions in a remote area in the South Atlantic Ocean.

Oceanus: What will you be doing?

Donohue: We’ll deploy all the new moorings, then recover the ones that have already been in the water for a year. I will be leading the mooring team, running deck operations, and making sure that everything goes smoothly and safely.

The mooring team handles the mechanical side of mooring ops. We do the rigging and check the instruments and moorings. We’re handling all the tools, we’re doing all the bolting together, making sure that everything is attached correctly. We operate winches and small cranes, and sometimes the ship’s A-frame, hoisting mooring components into and out of the water. As the lead, you direct the show.

Oceanus: I’m guessing you didn’t learn how to do all of this in school. So how did you learn it?

Donohue: I feel like it was just so intuitive, and just came so naturally to me, that I don’t quite know how to say when or how I learned it.

I think actually being in sports and being a hard worker helped a ton—knowing how to be a team player, and wanting to work with your hands, and use tools, and understand how they work. As well as having that oceanographic research background combined with the small vessel background.

Because I’m smaller than the majority of the people that I work with—I’m five-foot seven-inches and one-hundred and fifteen pounds—I approach things slightly differently. So I’m purposely going to go out and use tools or make tools in order to complete something that someone else may just go out and manhandle.

I’ve always had the attitude of, “I’m going to get it done somehow and make it happen.”

Oceanus: How much time do you spend on research cruises?

Donohue: Every year varies, but I would say I spend three to four months out at sea or away from home, conducting research for WHOI. I had to be shore-side for a little while because I had my first kid in February, so that kinda threw things off.

Oceanus: How did you handle being pregnant and doing a job that has you out at sea so much?

Donohue: Well, I’m very stubborn! And I wasn’t going to let a pregnancy be a moment that stopped me from being able to proceed with what I was always doing.

If anyone said I shouldn’t be doing that, I kept reminding them, “Look back at your ancestors. They were doing hard manual labor while they were pregnant and giving birth in the fields. It’s not like our bodies aren’t designed to be able to handle this.”

I was able to continue working up until the day I had to go to the hospital to give birth. I continued to go out to sea up until seven months.

The last cruise I did, I was running the deck ops for the R/V Connecticut in Cape Cod Bay. In November. In the cold. And here I am with my big belly out on deck, and everyone’s like, “Oh, don’t do that.” I was like, “Eh! I’m fine, as long as I don’t lose my balance.” I had helpers with me too, at that point, to do the heavy lifting. But I was the one that was still running the show.

Oceanus: What about after your little girl was born?

Donohue: I had to be careful because I didn’t have the strength that I had before she was born—just because your muscle structure changes, and you slowly stop lifting stuff as you are becoming more pregnant. So I knew I had to regain that and just be careful not to cause a lifting injury.

I’m the only female that works for the WHOI mooring group, but most of my co-workers are fathers. They understood what their wives went through with trying to nurse their children and everything, so they were supportive. But we had to figure things out with me being able to pump at work.

Oceanus: You’re talking about needing to pump breast milk at work.

Donohue: Yes. Navigating that is interesting—figuring out the logistics of pumping on a ship, making sure that the crew was OK with it, having a space to be able to do that. I refer to it as “Momma Time” or “Momma Break” now, since people understand what that means without my using words that may make some people uncomfortable. But I would rather just be able to say, “I’m going to go pump,” since that’s just a part of life. I shouldn’t have to dance around it.

On one cruise, we set it up so that I could ship all of the milk I pumped back home, so my daughter would have milk while I was out on another trip later on. You treat it like you’re shipping back biological samples for science.

The team of co-workers I had out with me, they were very supportive about it. But I would always wait until there was a lull in the activity, where I knew that I wasn’t going to be needed right away, and that it wouldn’t be impacting operations.

Oceanus: It must be really hard to leave your daughter for long periods of time, while you’re away on a research cruise.

Donohue: It’s definitely very difficult. You have to have a very good, strong support network at home. You need to have the support of your co-workers, too. Because you’re depending on them to help you while you’re out with them.

And then you also, you just have to have the mindset. Be like, “OK, it’s just going to be for this amount of time. You can handle this and get there for this trip.”

Oceanus: How old is your daughter?

Donohue: She’s seven months. She’s at the point where we know she’ll be crawling or maybe even walking by the time I get home. There’s also a good chance that she may say her first words.

So it’s just knowing that you’re going to be missing those, you know, gets a little …

You feel guilty leaving, making your husband a single father all of a sudden, albeit for a short period of time. Because you just want everything to go smoothly, and you know it’s not going to happen.

We’re not the same as a military family, but military families are probably the closest thing to an oceanographic, seagoing family—as far as the time we’re committed to be away from home in remote locations for long periods with limited communications, sacrificing holidays, birthdays, weddings, funerals, school events. You just have to balance everything.

Oceanus: Have you been able to get advice from other women working in oceanography?

Donohue: There are various other WHOI new moms who have been really great at supporting me in this.

But I had definitely had it brought up to me multiple, multiple times during my entire career, of people constantly telling me, “Well, if you have a family, you’re done, you’re out of this career.” And I watched it happen to a lot of the female technicians that I’ve worked with in the past, that as soon as they had a kid, they stopped and just didn’t proceed.

I feel like I’m doing this not only for myself and for my daughter, but also for all those other women, to give them a pathway to say, “Look, this is actually doable. You can make it happen.”

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Mooring technician Meghan Donohue joined WHOI's Mooring Operations and Engineering group in August 2014. She was the first woman to do so. (Photo by Peter Wiebe, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- In the fall of 2016, Donohue participated in a research cruise to the Global Argentine Basin Array, one of four global arrays operated by WHOI as part of the Ocean Observatories Initiative. Donohue led mooring deployments and recoveries on the cruise. (Illustration by Jack Cook and Eric Taylor, WHOI Graphic Services)

- Donohue (on buoy) connects a surface buoy to a crane that will hoist the buoy into the water from the deck of the research vessel Atlantis. The buoy is part of a scientific mooring that was deployed in February 2015, on the first Ocean Observatories Initiative cruise to the Global Argentine Basin Array. (Photo courtesy of Meghan Donohue, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Dononhue changes the rigging of a subsurface float that was just pulled out of the water at the Global Argentine Basin Array in the South Atlantic Ocean. Research cruises to remote locations such as this one can often last a month or more. (Photo by Diane Suhm, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Sometimes mooring deployments continue into the night. After a long and challenging deployment, Donohue waits for the countdown to cut the safety strap and release the anchor, the final component of a mooring to hit the water. (Photo by Jared Schwartz, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)