Why we explore deep-water canyons off our coast

Knowledge gained from this study is informing decisions about activities that could affect these canyons and the precious species and resources they contain.

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2022

This article printed in Oceanus Summer 2022

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

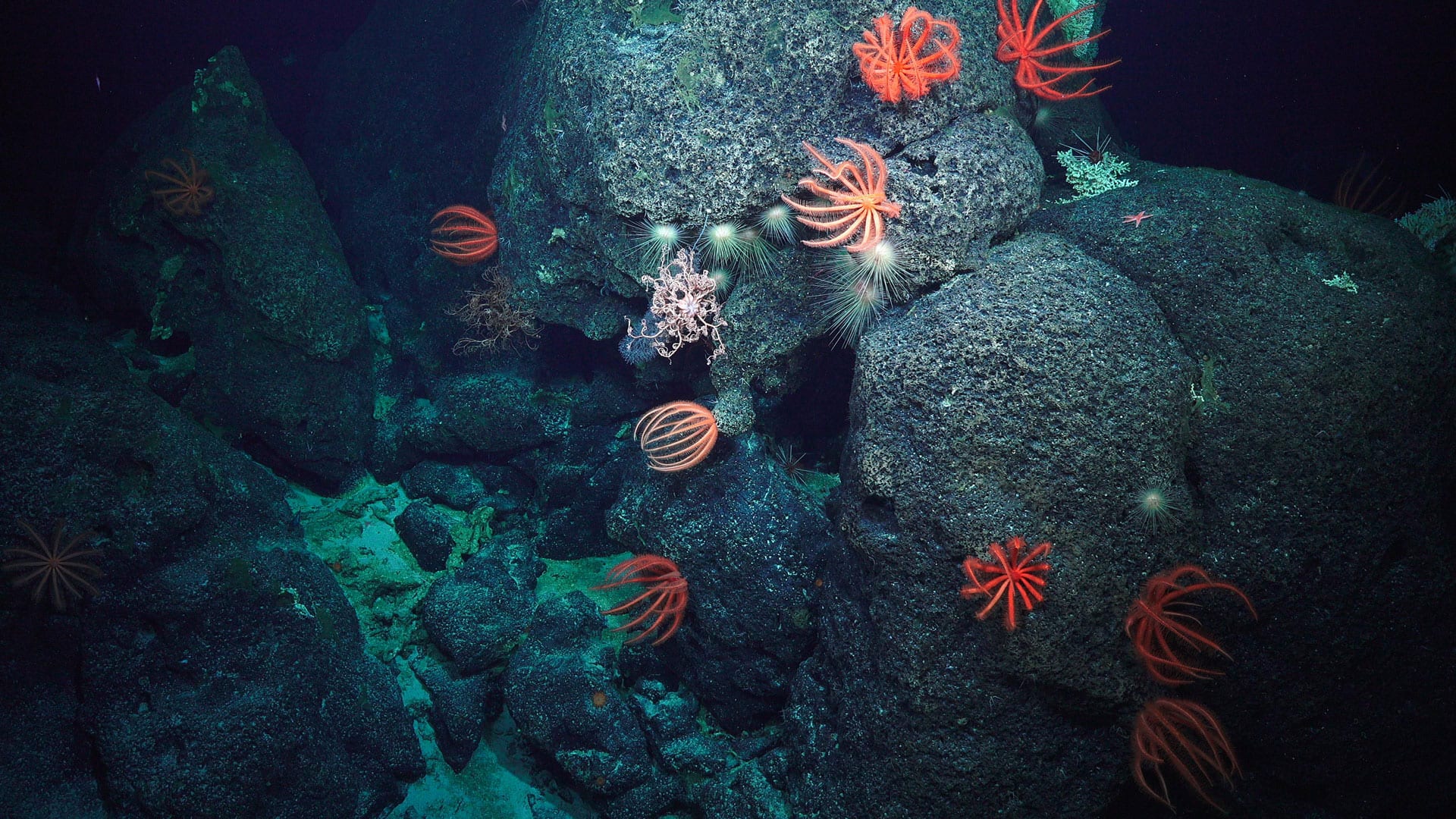

When someone mentions corals, the first image that likely comes to mind is of brightly-colored reefs in shallow, turquoise blue tropical waters. But not far from the busy ports and densely-populated cities of the U.S. East Coast, the deep-sea canyons of the Mid-Atlantic Ocean are home to a remarkable abundance and diversity of corals, sponges, anemones, and fishes. Little-known to the 34 million residents on shore, these 90-plus canyons and their deep-water habitats are some of the most productive on the planet. Their resources include unique habitats, yet undiscovered species, and potential biomedical and pharmaceutical products. Deep-water coral ecosystems also help support valuable commercial fisheries.

But human activities and their impacts are putting these unique ecosystems at risk. Deep-water corals and other canyon inhabitants are vulnerable to rising ocean temperatures, ocean acidification, physical damage from bottom trawling, and other destructive seafloor activities. Thousands of these corals are likely more than 500 years old—but they grow only a few microns (about 0.00004 inches) each year, which means they recover from damage very slowly, if at all.

Although extensive deep-water coral communities were first discovered in the 1970s, these specialized ecosystems have remained largely unexplored. A team of WHOI scientists led by biologist Tim Shank recently set out to document life in the canyons, in collaboration with the Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean (MARCO) and three groups from NOAA: the Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program of the NOAA Fisheries Service, the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, and the National Ocean Service.

Shank and his colleagues used a ship-tethered digital camera system to examine patterns of animal life and compare habitat types within and among the canyons. They conducted 28 surveys resulting in more than 45,000 images.

Shank’s team found that deep-water corals often dominate the seafloor canyon landscape. They identified and recorded the locations of thirteen major types of hard and soft corals in eight canyons. Large, deeply V-shaped canyons with steep vertical walls supported the greatest diversity and abundance of corals and fish, while areas heavily impacted by erosion and sedimentation—such as the heads of canyons—hosted dramatically different and far fewer species.

The knowledge gained from this study is already having an impact. Shank has briefed Congress multiple times over the past year about the importance of diverse coral ecosystems in U.S. waters, and his work is helping to inform decision-making about activities that could affect these canyons and the species and resources they contain.