When it comes to albatross ‘divorce,’ climate isn’t the only issue

Personality can factor into lovebird split-ups in the southern Indian Ocean

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

There’s love. And then there’s avian love.

Few animals put on a show of affection like the wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans). Each year when these polar seabirds reunite after a long hiatus during breeding season, adult pairs often launch into a tightly synchronized and gregarious ritual. Standing a few feet apart from one another, they spread their wings, screech to the sky, and then click-clack their bills together. It’s about as close to a Hallmark moment as you can get in the southern Hemisphere.

These birds are good at showing love—and really good at maintaining it. Albatrosses are among the most fiercely monogamous of all seabird species, and often spend several decades of faithful lives together.

These relationships, however, aren’t always for keeps: wandering albatross couples do split up—a phenomenon researchers call ‘divorce.’

Why? For some species, it has lot of it has to do with our changing climate. Last year, a study in the journal Royal Society Proceedings B looked at 15,000 pairs of black-browed albatrosses (Thalassarche melanophris) breeding in the Falkland Islands over a 15-year period. The researchers discovered that during years of unusually warm water temperatures, divorce rates soared from between 1-3 percent to as high as 8 percent (that may be high for albatrosses, but pales in comparison with the current 40 percent divorce rate among humans, and 85 percent divorce rate among Emperor Penguins.)

Increasingly warmer waters in the poles mean less fish and nutrients for albatross to consume during foraging trips, in turn forcing the birds to travel farther to find food. These longer journeys—which can span 1,800 miles (3,000 kilometers) or more—may be critical for survival, but they don’t always bode well for the relationship. They can trigger stress hormones that interfere with mating, and leave birds with less energy to raise chicks when breeding is successful.

Francesco Ventura, the study’s lead author from the University of Lisbon, says the added stress of long-distance travel may even cause some unhappy females to play the blame game.

“We propose this partner-blaming hypothesis—with which a stressed female might feel this physiological stress, and attribute these higher stress levels to a poor performance of the male,” says Ventura, who will be joining WHOI as a post-doctorate scholar in November, 2022.

Longer foraging trips can also cause albatrosses to return to their wintering grounds late into the mating season—and perhaps just a tad too late for love. By the time they arrive, overworked and exhausted birds may find themselves left in the dust as their partner has moved onto someone new.

While the changing climate may be leading to more divorce among black-browed albatrosses, researchers have recently found evidence of a more anthropomorphic reason for the split-ups among wandering albatrosses: personality. It turns out, shy guys finish last.

Ruijiao Sun, an MIT-WHOI Joint Program PhD. student, along with WHOI associate scientist with tenure Stephanie Jenouvrier and colleagues from the University of Liverpool and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), published a study in September, 2022 in the journal Royal Society Biology Letters suggesting that the chance of divorce among wandering albatross can be influenced by how shy, or bold, male birds are. Shy males, according to the study, tend to avoid confrontation so when an albatross “intruder” comes along vying for their female partner’s affection, the shy bird may give up on the relationship and leave the nest. The study found that the shyest male birds were up to twice as likely to divorce as their more aggressive rivals.

To establish a link between personality and divorce, the researchers combined a whopping 70 years of albatross demographic data from a colony on Possession Island in the southern Indian Ocean with more recent “personality” data collected there during breeding seasons since 2008.

The demographic data has been collected during site visits to the nests during each breeding season since the 1950s to determine the identity of parent pairs and their breeding success. Newly born chicks are banded with unique ring number during these site visits.

Researchers presented a foot-high inflatable blue cow, named Betsy, to the birds and then recorded their reactions. (Photo by Susan Waugh)

Measuring albatross personality was more complicated. Researchers had to construct a pole-like track from carbon fiber on which they could glide a foot-high inflatable blue cow—named Betsy—toward the birds. A tiny wide-angle camera was mounted on the cow’s horns to capture the albatross reactions to this object they had never seen before. It was a brilliant setup for a bird personality experiment—at least until Betsy became a target for one of the more aggressive albatrosses.

“During one of the measuring seasons, Betsy got ripped apart by a really bold albatross,” says Sun.

Albatross reactions were scored from 0-4, with lower scores indicating shyness (i.e., little or no reaction) and higher scores indicating boldness (i.e, standing up and calling out). Once the scores were synthesized with the demographic data, the researchers were able to determine that the shyer males—those that showed little or no response—had higher divorce rates and were most likely being forced out of their pair bonds by homewrecking males. The researchers were surprised by the results.

“At the beginning, we thought bold individuals in the colony would have higher divorce rates because we consider divorce as a risky behavior,” says Sun. “If they were bold, we figured they may divorce more often so they can gain more breeding opportunities with different partners. The fact that it was the shy ones getting divorced was opposite to what we were expecting.”

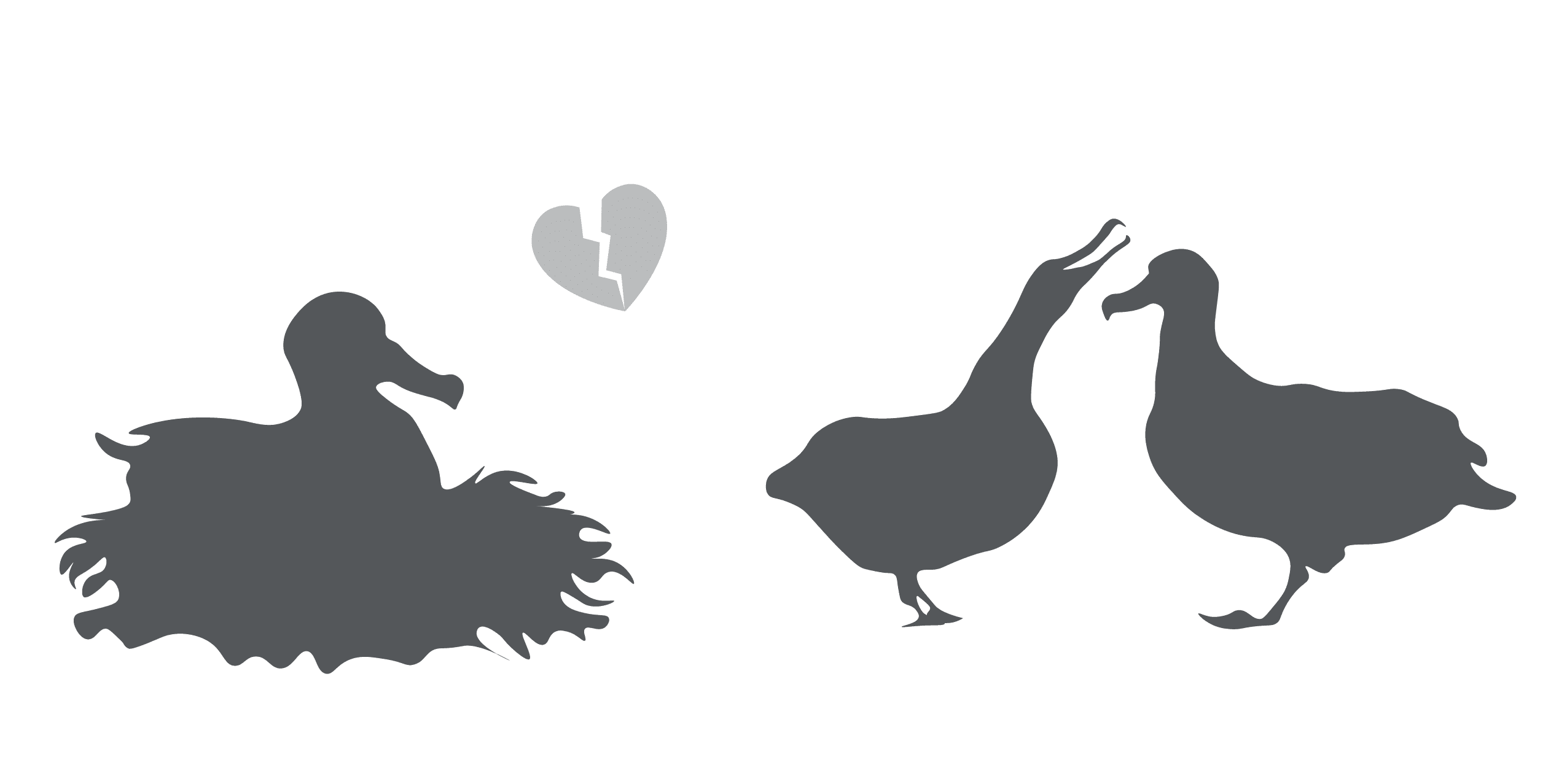

Jenouvrier, Sun’s advisor and senior author of the study, points out that divorces in the colony did not appear to be adaptive—whereby a female leaves her partner to find a better mate for better breeding success.

“Sometimes birds split up to find a better mate and raise more offspring,” Jenouvrier explains. This is called adaptive divorce and has been observed in many bird species. However, in wandering albatrosses, individuals do not have more chicks after a divorce and females are unlikely to benefit from seeking new mates.”

Rather, the couples seemed to experience what Jenouvrier calls “forced divorce”—when a male intruder steals a female away from her timid male partner. The females weren’t actually looking to ditch their shy guys, and personality didn’t play a role in their decision to move on to a bolder bird.

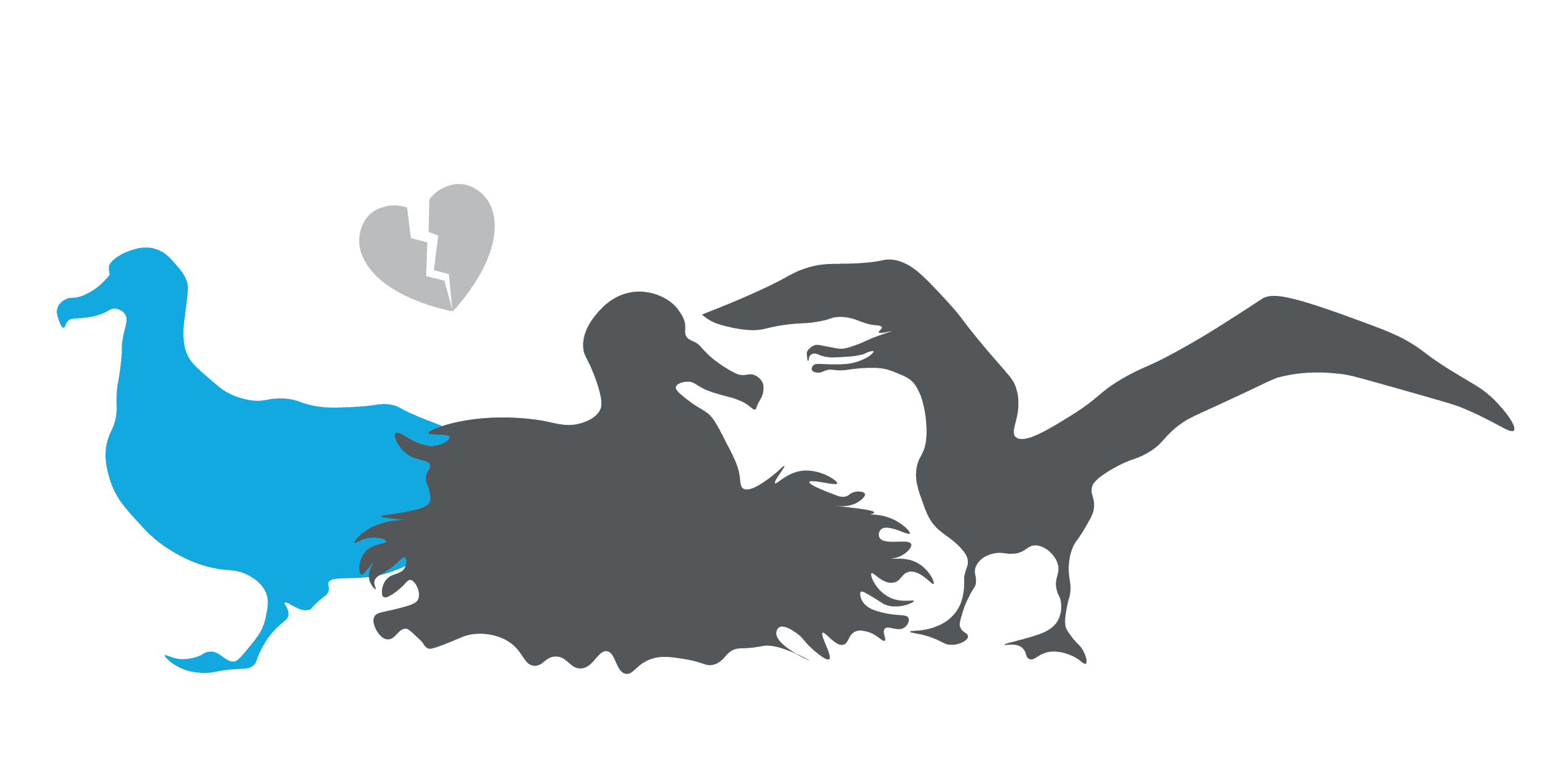

Forced vs. Adaptive Divorce in Seabirds

Whether forced or adaptive, divorce for these lovebirds doesn’t sound all that pretty. But is it necessarily a bad thing for them?

On Possession Island, it largely depends on gender. The number of males far outweigh females there, so the cost of divorce can be huge for males since it may take them years to find a new partner to breed with. “Previous studies on lifetime reproductive success of these birds clearly show that divorce can be a big disadvantage for males,” says Sun. “It can cause them to miss multiple breeding seasons and end up with fewer offspring.”

But if and when a female albatross becomes single, it’s usually not for long. They often just resume breeding with their new mates within the same season.

Of course, there could still be a cost to divorce for females in the colony. Perhaps they won’t have the same breeding success with a new partner, or maybe they’ll need to exert more energy during the breeding process—an energy cost that could make the birds more vulnerable to foraging risks.

The grass, after all, isn’t always greener.

Funding for this research was provided by National Science Foundation grants NSF-OPP 1840058 and NSF GEO-NERC 1951500.