This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2025 - SPECIAL ISSUE

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

On March 20, 2024, a North Atlantic right whale discovered adrift 50 miles off the coast of Virginia sparked a flurry of unanswered questions.

The 35-year-old mother had recently given birth to her sixth calf. Why would a seemingly healthy female in the prime of her life suddenly die? A necropsy provided the answers, revealing catastrophic injuries—a dislocated spine and multiple fractured vertebrae—consistent with blunt force trauma from being struck by a seagoing vessel.

This accident victim was one of three known right whales to die from vessel strikes in 2024. These incidents—along with fishing rope entanglements—are alarming given that only approximately 370 right whales remain in the world. Their untimely deaths highlight a disturbing trend, the accidental injury and death of whales, dolphins and other marine mammals, caused by collisions with vessels of all sizes including container ships, cruise liners, sport boats and more.

An adult whale weighing 25-40 tons, roughly the size of an 18-wheeler, stands little chance against a container ship tipping the scales at 225,000 tons. Images of whales draped across ship bows, dwarfed by the looming vessels, vividly illustrate the peril. The towering 20-story ships pose a danger to migrating whales akin to crossing a six-lane highway for humans—a journey that can easily prove fatal.

Dr. Michael Moore, a seasoned marine veterinarian at WHOI, has witnessed this rising threat firsthand. Over his 40 years responding to whale strandings, he has performed necropsies revealing shattered skulls, broken jaws, dislocated vertebrae, and deep torso lacerations. His work underscores the urgent need for innovative solutions to help prevent these tragic accidents.

“The trauma often results from a spinning propeller, or from being struck by part of the vessel, such as the bow,” Moore explains. “The risk appears to increase with vessel speed.”

A whale hit by a vessel moving at 10 knots or less has a better chance of survival than one struck at higher speeds. Moore advocates for rerouting ships away from whales whenever possible or requiring them to slow down in known migration zones. While some progress has been made with speed restrictions, enforcing these measures remains challenging. New technological solutions are essential to protecting these endangered mammals.

Many of those solutions originate from WHOI’s innovative research. “Technology to prevent collisions is crucial,” Moore emphasizes. “Our scientists have translated fundamental scientific understanding into useful tools.”

Among these is Dr. Mark Baumgartner’s Robots4Whales program that relies on the WHOI-developed digital acoustic monitoring (DMON) instrument. This underwater microphone is situated in a weighted frame resting on the floor of the ocean, or in a deployed glider, capturing whale sounds and transmitting information about those sounds every two hours to shore. The signals are analyzed in Baumgartner’s lab at WHOI and posted on a publicly accessible website, robots4whales.whoi.edu, sharing crucial detection information with scientists, industry, and government officials to support conservation measures like NOAA’s Slow Zones for Right Whales, a voluntary vessel speed reduction program.

This acoustic data enables the posting of near-real-time alerts for vessel operators and helps plan rerouting strategies. Baumgartner compares it to the warning signs and flashing lights in school zones: “You know kids are around, but you don’t know exactly where any one kid is located,” he explains. The system can detect right whales from up to five miles (eight kilometers) away, providing advance notice for ships to slow down or alter course. “As long as there isn’t a loud vessel in the immediate vicinity of the buoy,” Baumgartner notes, “the instrument can effectively detect whales at significant distances.”

He points out that, although the natural lifespan of right whales is typically 80-90 years, we no longer see older whales because mortality from vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglements cut their natural lifespan nearly in half. Baumgartner hopes his acoustic buoys can help reverse this trend and significantly boost the whale population over the next decade.

“It’s a long road,” he admits, and industry participation is vital. That’s why collaborations between WHOI and shipping giants like CMA CGM are so important. Over the past three years, CMA CGM has supported the operation of two acoustic buoys off the coasts of Savannah, Georgia and Norfolk, Virginia. WHOI has recently extended this partnership to continue monitoring efforts with CMA CGM, a French company with a long history of supporting other whale protection initiatives like slow speed zones.

The number of acoustic buoys has grown to eleven along the East Coast and two on the West Coast, complemented by many underwater gliders equipped with similar monitoring gear operated by WHOI and partner institutions. Baumgartner envisions more shipping companies following CMA CGM’s lead and embracing sustainable practices that prioritize whale protection. The more industry players that get involved, the better the chances for safeguarding these vulnerable creatures.

Meanwhile, Dr. Daniel Zitterbart, associate scientist at WHOI, and his team are exploring additional strategies. They’ve developed a thermal imaging system that detects whale surfacings, exhalations, and blows, using heat signatures.

“Nobody wants to run over a whale,” Zitterbart says.

But with up to 20,000 whale strikes per year, it still happens far too often, hence the need for an approach that adds a new layer to whale protection technology.

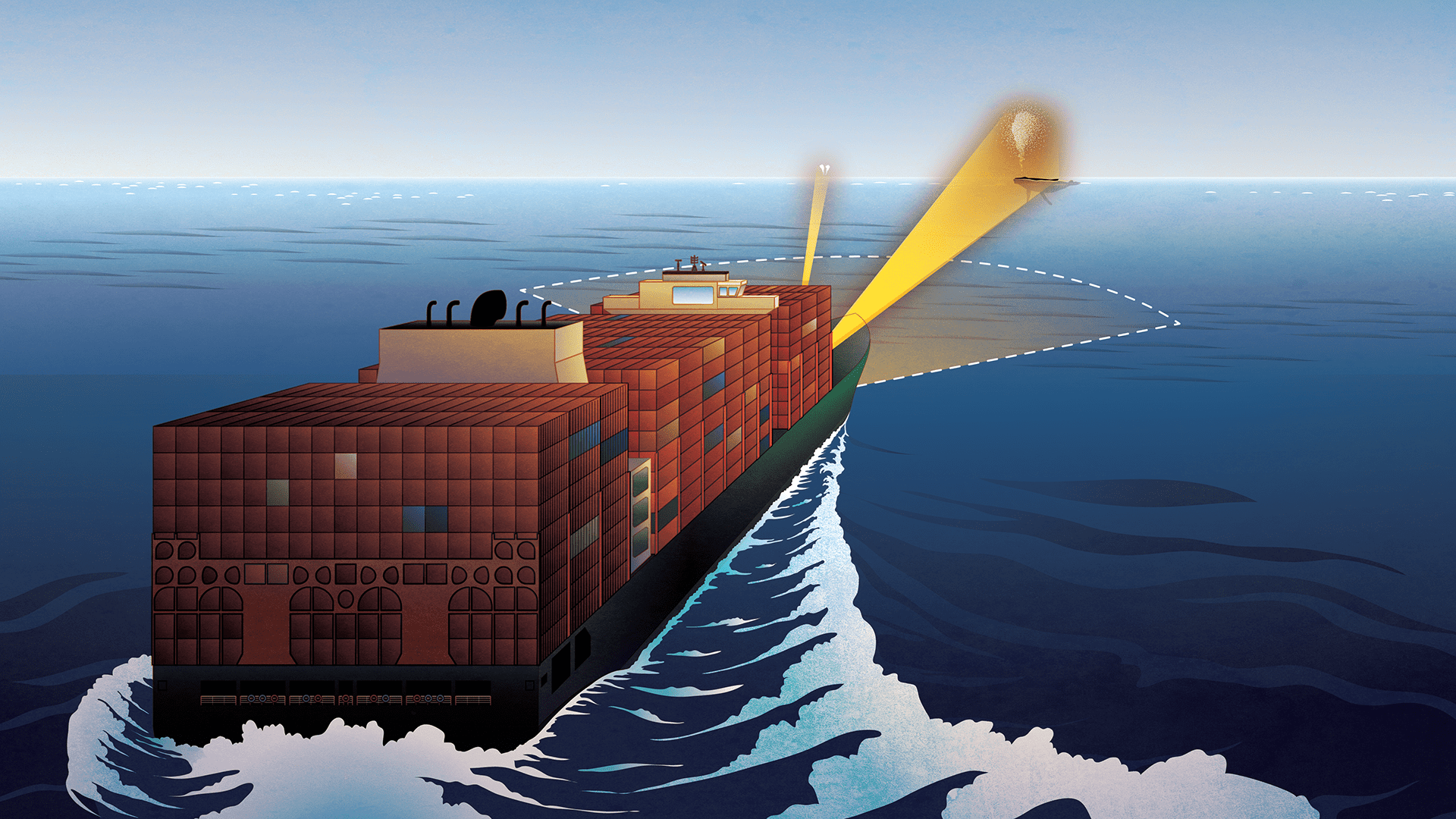

When a whale blows, its thermal signature is recognized by an integrated artificial intelligence (AI) program that alerts vessel crews within seconds to the presence of whales up to several kilometers away. This gives vessels enough time to slow down or change course.

The software employed also enables the system to filter out thermal signatures of boats, birds, and waves. All suspected whale detections are reviewed remotely, within seconds, by a human analyst to avoid false alarms. The thermal cameras offer the advantage of being effective day and night and during periods when whales might be silent or when ambient sound levels are so high that whales cannot be heard. Since the team deployed their thermal cameras in 2019, detections have skyrocketed from 78 in the first year to over 50,000 in 2024, with zero false alarms.

The thermal camera systems, available through Whalespotter.AI, have been deployed at strategic locations—from container ships and fast ferries to key coastal sites like the Port Wilson Lighthouse overlooking Puget Sound in Port Townsend, Washington, where the Southern Resident killer whale, an endangered orca species, is monitored.

The next step for acoustic buoys and thermal cameras is to further partner with industry to scale whale detection devices and increase their presence in, and near, the ocean to help preserve these magnificent but vanishing mammals.

“Slowing down is good,” Zitterbart says, “but avoiding the whale altogether is even better.”