The Bounty of the Ocean

Researchers work to harness the untapped benefits of the sea

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2020

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2020

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

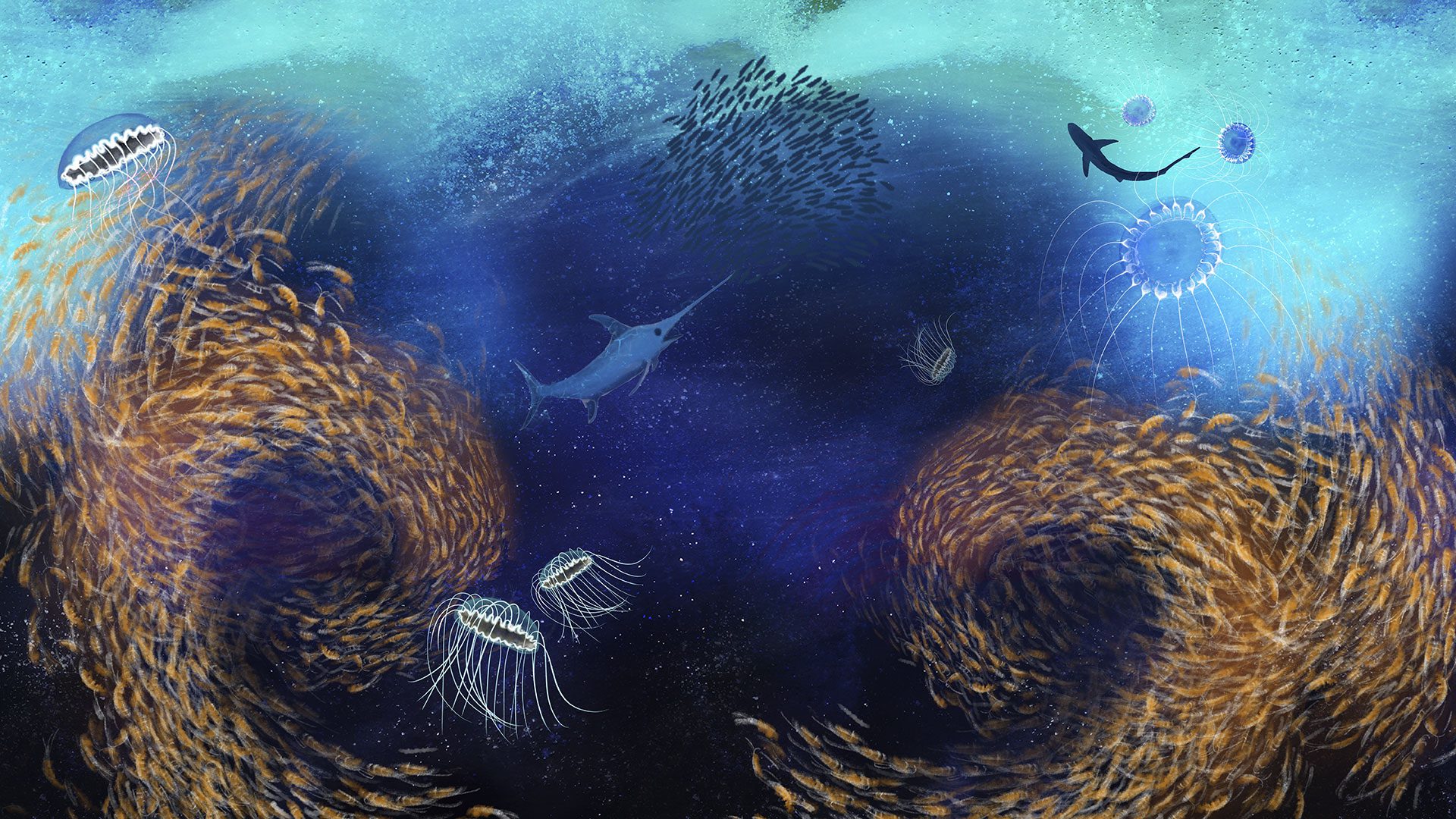

Just as there are many human health risks to contend with in the marine environment, the global ocean is a vast and bountiful treasure chest of resources we rely on every day to support our existence. Protein-rich sustenance, medical treatments, and physical and mental well-being are just some of the ocean-related benefits societies have taken advantage of for centuries.

Recognizing the critical importance of the oceans to our own health—and the planet’s—ocean scientists are working to investigate the untapped potential of the sea in order to maximize these benefits, and to help ensure the ocean’s bounty for generations to come.

Farming the ocean

Fish and other marine animals are a rich source of protein. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that 3.3 billion people rely on this protein source to meet 20 percent of their dietary needs. Seafood also provides an important source of micronutrients, like Omega-3 fats, iodine, iron, Vitamin D, calcium, and zinc, which have been shown to reduce cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases.

Aquaculture—the breeding, rearing, and harvesting of fish, shellfish, and algae in all types of water environments—is also a key source of high-protein seafood for a hungry world. The United States imports 2.5 million tons of fish annually, half of which is reared in an aquaculture setting. Aquaculture produces slightly more than half of all human seafood to accommodate the global diet.

Scott Lindell, a research specialist at WHOI, says marine aquaculture—particularly farmed shellfish and seaweeds—provide essential micronutrients and bioactive compounds for human health.

“They beat virtually all means of calorie and protein production on land,” says Lindell.

Aquaculture can also benefit human health in other ways. Lindell refers to diets based on farmed fish and seaweeds as “low-carbon” diets that ultimately could help mitigate some of the effects of climate change.

“Lowering one’s carbon footprint can help slow down, and hopefully one day, reverse climate change that threatens global health and human health,” he says.

Fish feed, food security

Like humans, fish need food security as well. Fish feed has remained a niggling problem when rearing fish in an aquaculture setting. Traditional fishmeal is composed of ground small fish, like anchovies and sardines, caught from wild fisheries that are stressed by climate change and overfishing. “Our future food security depends on alternative fishmeal and oil products to supplement aquaculture feeds that are environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable,” says Stefanie Colombo, assistant professor in the Department of Animal Science and Aquaculture at Dalhousie University. Colombo is working alongside her col-leagues to develop a plant-based fish food to reduce the need to harvest fish from the wild to feed farm-raised fish. The alternative feed has a similar nutritional profile as traditional fishmeal and fish oil at roughly the same cost. “Without aquaculture, neither food security nor ocean conservation are attainable,” Colombo says. “It is exciting to see the development of new, innovative products that [if they] prove to be successful in aquaculture, will help the sustainability issues we are faced with, in regard to seafood production.”

David Bailey, a research associate at WHOI, says aquaculture provides more than just a sustainable source for food. It offers an important ecosystem service—the benefits gained from the natural environment.

Shellfish, like oysters and mussels, are filter feeders. As these creatures draw water into their bodies, they capture bits of food on their screen-like gills. By removing these tiny morsels, the shellfish release cleaner, clearer water back into the environment. While all shellfish have their own filtration rates, a single adult oyster can filter as much as 50 gallons of water per day. Through filter feeding, shellfish increase their muscle mass and grow their shells.

Seaweed, a generic name for the countless species of marine plants and algae, also offer a crucial ecosystem service. These plants draw on nutrients, like phosphorus and nitrogen, from the water to fuel photosynthesis, the chemical reaction that combines sunlight and dissolved carbon dioxide in the water to create biomass. By removing carbon from the water, these plants reduce regional water acidification while promoting biodiversity in the ecosystem. It all adds up to a cleaner and healthier marine environment for coastal communities.

Some communities are even using shellfish aquaculture as an alternative to sewering. Estuaries in the small coastal town of Falmouth, Mass. are seeded with oysters and clams that feed on algae that thrives on nitrogen flowing from leaky septic tanks. The shellfish remove the unsightly algae that sucks oxygen out of the water at night or when they die—reducing the estuary’s nitrogen load in the process. Relocating the shellfish to clean water for a season allows the mollusks to flush out any contaminants they may have picked up in the more polluted estuary. It’s a win-win: the community saves money by not having to transport and clean as much wastewater at treatment plants, and a healthy shellfish harvest provides an economic benefit.

Going deep for new treatments

Most people view the ocean as a source of food, a site for recreation, and a mode of transport, but scientists believe the ocean holds potential treatments for many chronic diseases, as well as a source for new antibiotics. Researchers are examining the myriad of compounds in venomous sea snails, for example, to develop new pain medications targeting pathways outside those triggered by opioids, as well as compounds that can regulate insulin to help patients manage diabetes.

Tim Shank, a marine biologist at WHOI, is also on a quest for biomedical treatments. And he’s delving into the deepest regions of the global ocean—the hadal zone—to find them.

The hadal zone extends beyond 6,000 meters below the ocean’s surface. This region is cold and devoid of light. Animals living in the hadal zone have evolved to endure the cell-crushing pressure associated with the extreme depth. Shank is keen to understand how these unique habitats may have forced adaptations in animal life that could ultimately help people.

Sea life at more than 8,000 meters deep photographed during a 2014 cruise to the Kermadec Trench. (Image by Tim Shank, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“At 6,500 meters depth, different groups of species emerge,” he says. “Pressure plays a huge factor in evolution of life on Earth, but we still don’t understand how.”

According to Shank, the hadal zone encompasses the deep trenches that form along subduction zones where tectonic plates converge. These trenches provide a perfect laboratory to study the evolution of novel species as a function of depth. These adaptations could lead to biomedical discoveries.

“The marine environment has long been a treasure trove for marine natural products—those that are naturally produced in the ocean—but the hadal region hasn’t really been explored for this yet,” says Shank. “I believe the trenches may support high biological diversity and thus great opportunities for natural products.”

Organisms living at hadal depth experience severe challenges. Under intense pressure, animal cells can lose their integrity and flatten. When the cell structure is compromised, vital proteins fail to fold properly. Marine organisms have adapted to this stress by producing molecules called piezolytes. These compounds join with water to act like tent poles that prop the cell up and allow proteins to fold and unfold properly. These insights could hold the key to understanding many human diseases that manifest from improper protein folding.

“Protein dysfunction is an end game,” Shank says. “It can lead to disease in humans, like Alzheimer’s, glaucoma, cystic fibrosis, and muscular dystrophy.”

Shank wants to study piezolytes and protein stability in hadal animals to improve our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases in people and possibly identify new treatments.

To capitalize on deep-water discoveries, Shank is leading the HADEX project, a program developed to explore the deepest regions of the ocean. The program was designed to classify the composition, diversity, and abundance of hadal organisms as a function of depth in the ocean. The team plans to explore the go-to food sources for these isolated communities, and to chart the energy and metabolic demands of life in this extreme environment. Finally, the researchers plan to explore the genetic diversity of these deep-water species to understand how isolated, or perhaps connected, these communities that stretch across the dark and extreme regions of the ocean may be.

Sources: NOAA, IPCC, Ocean Panel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Calming Ocean

The health benefits of the ocean extend from the imposing hadal depths to welcoming coastlines. The rhythmic waves, fresh air, and vast landscapes offer an idyllic opportunity to reset and recharge from the stress of modern life. Today, scientists are working to quantify the health benefits of coastal environments to improve mental, physical, and emotional health.

Previous studies have found that people who live near bodies of water experience an enhanced sense of well-being. Researchers have coined the term ‘blue space’ to describe the benefits of environments close to lakes, rivers, and coastal regions. ‘Blue spaces’ have been associated with lower rates of depression and stress. These environments also promote more physical activity and positive social interactions. These findings beg the question—can a doctor prescribe a trip to the coast to treat some of the chronic diseases that afflict society today?

“People intuitively feel the benefits when they are at the coast,” says Mathew White, senior lecturer at the European Centre for Environment and Human Health at the University of Exeter Medical School. “Using representative survey data, we have found that [people exposed to] areas with [objectively-rated] higher biodiversity have better psychological experiences. They are benefiting from the complexity of the natural world.”

In one study, White and his colleagues used data from a large representative health survey obtained from 26,000 residents across England to examine the impact of proximity to the ocean on mental health. The participants lived in communities that ranged from half a mile to 30 miles from the coastline.

Surprisingly, the researchers found that participants, particularly those from the lowest socioeconomic households, who lived closest to the ocean were 22 percent less likely to display symptoms of mental health disorders, such as anxiety and depression. For White, this finding is critical, because it addresses a segment of the community that is often more susceptible to chronic diseases, like obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke—diseases that pose the greatest burden on the healthcare system.

Scientists are focused on understanding the mechanisms and pathways behind the health benefits provided by ocean access, and which coastal recreation activities provide the greatest mental and physical benefits for well-being and disease reduction. (Photo by Gabrielle Elleirbag © Unsplash)

Partly in response to this work, the government of the United Kingdom has developed a ‘blue belt’ to preserve biodiversity and habitat along the island’s coastline. To date, more than 350 marine protected areas spanning almost 85,000 square miles of coastline have been set aside to form the belt.

White and his colleagues are also trying to ‘bottle’ the benefits of the coast. They developed a virtual coastal program to help people who cannot easily access this environment. They are testing the program with dental patients during surgery and have found that patients that use the program experience less anxiety and require fewer medications for pain.

White acknowledges that more work is needed. His group, as well as the WHOI-led Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health (OHH) and other OHH centers, are focused on understanding the mechanisms and pathways behind the health benefits that ocean access provides. In addition, these groups aim to understand which coastal recreation activities provide the greatest mental and physical benefits for well-being and disease reduction.

“By demonstrating the health and well-being benefits of the coast, we can improve access for people [from all socioeconomic incomes],” says White. “If we can transfer medical budgets to health protection and promotion rather than care because things have gone wrong, we can improve the length and quality of people’s lives [as well as] protect the natural environment. It is a win for everyone.”