The Bermuda Station SA Long-Running Oceanographic Show

Deeper Waters Show Warming Trend

December 1996 — A time series of hydrographic measurements was initiated at Bermuda in 1954 and continues to the present. It began under the banner of the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958) with the scientific support of Henry Stommel of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and William Sutcliffe, director of the Bermuda Biological Station (BBS). The scientists and personnel of the originating institutions have been the most active participants over the years, but the data have been widely used by the international oceanographic community. While other long time series of measurements in the North Atlantic began in association with weather ships, only the Bermuda measurements have a strong oceanographic focus.

In recent years, large international programs including the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) and the Joint Global Ocean Flux Study (JGOFS) have provided scientific justification for continuation and expansion of the multidisciplinary Bermuda measurements. As these programs begin to wind down, it is important to recognize the significance of this time series study to understanding of climatic change: These measurements are the principal source of information about subsurface changes in the Sargasso Sea and the subtropical gyre over the past four decades. In early years, the time series was denoted by the attribution “Panulirus,” the name of the small BBS research vessel used to carry out the sampling. However, over the years, several other research vessels have serviced the site, and the present practice is to call the time series Station S, in keeping with the convention for many weather ship sites.

In the field of physical oceanography, Station S is not optimally located: There are no major water masses formed there, and the circulation of the subtropical gyre and deep boundary currents only peripherally affect the island. However, its location in proximity to these major North Atlantic circulation features make it ideal for determining larger-scale changes in the basin as they pass by. To make an analogy with the study of automobiles, a researcher might visit various factories to study manufacturing and design changes or just sit by a busy highway and observe the passing traffic—Station S fits the latter category very well. In the short space available, we wish to discuss some of the changes observed at Bermuda, what they import for the North Atlantic, and possible reasons for their occurrence. We will only look at two “layers” in the water column, the Eighteen-Degree Water and the North Atlantic Deep Water.

Eighteen-Degree Water was first described by WHOI physical oceanographer Valentine Worthington in 1959 as one of the major water masses formed in the northern Sargasso Sea in late winter: It is the principal type of subtropical water found in the North Atlantic. It occurs at depths of a few hundred meters at Station S and is characterized by a layer of nearly constant density having a temperature of about 18°C. While this layer does not form at the surface near Bermuda, it occurs just below the depths of late winter mixed layers near the island and is closely coupled to surface layers found there. The Station S time series has been one of the main barometers (or, more correctly, thermometers) of changes in this water mass as it flows by the island from source regions to the northeast.

The thickness of Eighteen-Degree Water varies by a factor of two over the course of the current 42-year time series. Temperature and salinity (density) changes also occur over time, and the layer temperature is only approximately equal to 18°C. In years when this Eighteen-Degree Water is produced in large quantities, the surface salinity (but not necessarily temperature) at Station S is high. In poor production years, the surface salinity is low. Thus, long-term changes in this water mass seem to be closely linked with processes that affect the surface salinity. High production periods seem to be recur at intervals of approximately 12 to 14 years. Many of us recall when Worthington convinced the funding agencies to mount a field study of Eighteen-Degree Water, only to find that none had formed that year. We can now see that the climatological minimum of the signal at Bermuda occurred during the mid 1970s when he went to sea! Our study of the processes controlling this variability has not provided a conclusive answer as to why this periodicity occurs and how it is linked to surface salinity—but not temperature—changes, though we believe it must have some connection with changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation over the subtropical Atlantic Ocean.

At depths of 1,500 to 2,500 meters at Station S, we find another clear signal that is not connected with atmospheric changes over the subtropical gyre. This is a slow increase in temperature over time with a trend that is apparent in records that date to the early 1920s when deep-water oceanographic measurements were first made near Bermuda with accurate reversing thermometers. The long-term trend of this temperature change is at a rate of approximately 0.5°C per century. It is one of the clearest examples of a long-term increase of ocean temperature in the subsurface ocean. That is not to say that the annually averaged temperature in this layer always increases. In fact there are decadal time-scale changes at this depth too, with 1993 appearing to be the coldest in 20 years. Since waters at this depth do not communicate with the surface anywhere in the subtropical gyre, it is the subpolar gyre to the north that is the most likely cause for the variability, if not the trend. Our present studies indicate that long-term changes in the production of Labrador Sea Water are associated with the decadal variability in the deep water at Station S. Since the Station S bottom is at about 3,000 meters, this deep layer is the deepest available in the time series. There appears to be a lag of 5 to 6 years until the Labrador Sea Water signal appears at Bermuda.

Many of the climate studies that can be undertaken using the time series at Bermuda are ongoing and of greater value as time goes on. This is related simply to the fact that phenomena with time scales of a decade must be studied with time series that span several “events” in order to make any statistically significant statements. The examples given above are marginal in the statistical sense because even the 42-year data set is not long enough—we are always left looking at the most recent years of data and wondering what will come next! For this reason it is essential that the observations continue beyond the lives of some of the large field programs like WOCE and JGOFS, which will end in a few years. Though it is possible that technological advances may enable additional measurements or more cost-effective methods, the Bermuda time series currently offers our principal window into the climate of the subtropical gyre of the North Atlantic.

The National Science Foundation has funded the Station S work over the years.

Terry Joyce was a member of the first class admitted to the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Physical Oceanography 1968. His first cruise, with Henry Stommel aboard Atlantis II that same year, made a port call in Bermuda, so his Bermuda connection extends far beyond this article. Since completing his doctorate in 1972, he has conducted research at WHOI except for a six-month stint in Germany. Though his research interests have changed over the years, there has always been a strong thread of seagoing work and data analysis/interpretation. For the past eight years, he has served as director of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment Hydrographic Program Office based at WHOI. Lynne Talley was also a WHOI/MIT Joint Program student, having begun her graduate career as a large-scale observational oceanographer working on items like Eighteen-Degree Water using the Bermuda record and Labrador Sea Water. She moved into theoretical studies of unstable currents for her degree, completed in 1982, but several years after moving on through a postdoc and beginnings of her research career she found herself squarely back in the intermediate and mode waters of the world, both literally and in print.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- During the cold winter of 1977, Val Worthington ventured out aboard as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Researcher to study the formation of 18° Water, one of the principal North Atlantic water masses, in the northern Sargasso Sea. In the photo, Worthington is leaving the "hero platform" after launching a Nansen bottle cast

- Unfortunately, Worthington?s efforts were devoted to a period of minimum production of this water. In contrast to this minimum period in 1976 (denoted by red curves of temperature and potential density), a period of maximum climatological production occurred in 1964 (blue curves). In both cases, the plot shows the annually averaged properties for both calendar years vs. pressure to reduce eddy noise. Note that the underlying thermocline at pressures of more than 600 decibars is similar in both periods: Changes are not induced from below.

- Unfortunately, Worthington?s efforts were devoted to a period of minimum production of this water. In contrast to this minimum period in 1976 (denoted by red curves of temperature and potential density), a period of maximum climatological production occurred in 1964 (blue curves). In both cases, the plot shows the annually averaged properties for both calendar years vs. pressure to reduce eddy noise. Note that the underlying thermocline at pressures of more than 600 decibars is similar in both periods: Changes are not induced from below.

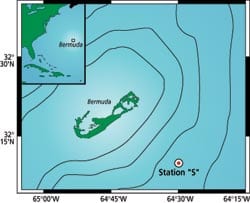

- The location of Station S is a short steam southeast from St. Georges? harbor. The smoothed bathymetry is plotted at one kilometer depth increments