The Airplane That Studied the Ocean

Former oceanographic 'flyguy' reunites with his old plane

Airplanes don’t typically come to mind when people think of ocean science. But for 25 years, beginning in 1945, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) maintained five planes for research. Ed Denton, who retired from WHOI in 1995, was hired three decades earlier to transform a former military plane into a flying oceanographic research machine, tailoring it for scientists’ needs.

He flew on it throughout the world, operating electronic instruments, and said he came to love that C-54 Skymaster aircraft like “a teenager who has refurbished and maintained a car.”

Butin 1970, he learned that funds to operate an airplane for oceanographic research had run out. The plane would be sent into storage in Arizona, a place Denton called “the bone yard.”

It was a loss for scientists, he said. They used the plane to cover vast areas of ocean in far less time than on a research vessel, for a variety of missions. One marine meteorology group at WHOI used it to study colliding air masses (better known as turbulence).

Other researchers collected data that ground-truthed satellite imagery, or chased buoys launched from ships. Another group took sea surface temperature measurements, which helped them to understand and better predict coastal cyclones and monsoons.

Denton went on to fly other planes, but like a first love, the C-54 maintained a special place in his heart. “I always thought about it,” he said. “I spent a lot of time on it; it was like a second home. For a lot of people at WHOI, ships are sacred places for them. That plane was like that for me.”

Lost and found

In early April 1997, Denton was visiting a friend who had moved from Cape Cod to California. One day, while his friend went golfing, Denton decided to tour the Aerospace Museum of California in Sacramento.

“After going through the exhibits in the buildings, I went to view the 30 or so old military and civilian aircraft parked outside. I was walking the rows, and I spotted a plane with a long fiberglass nose,” which was unusual for that type of plane, Denton said. “Something funny got to me. My senses told me there was something very familiar here.”

He read the red plastic placard on the stand in front of the plane, titled C-54D Skymaster, and stopped at the words indicating that its final assignment was with the Office of Naval Research in Boston.

“Whoops, I thought. Wait a minute. That was our sponsor,” Denton said. “At that point I began to reread the specs. Holy cow, there it was, the registration number staring me right in the face—50874. It’s a number I know like my own birthday. I think I went into slight shock. Here she was, 27 years after leaving Otis Air Force Base (on Cape Cod), still in one piece, standing there, and looking good. It was the aircraft that was responsible for my 32 years at WHOI,” he said.

As Denton absorbed the information, a stranger approached him. “I guess I must have been yelling to myself, because a man standing nearby came over to ask if I was all right. I just kept repeating, ‘It’s my old plane, it’s my old plane.’ ”

Still in one piece after all these years

Denton rushed around examining the aircraft, finding old hatches he had created for cameras that photographed clouds, locating antennas he had mounted on the craft’s belly, and pointing at holes he had drilled in the Plexiglas windows so scientists could poke thermometers through to measure air temperatures.

“It all came back in such a rush I was literally moved to tears,” Denton said. He walked to the museum office and asked if they ever opened the cockpits. A volunteer, moved by Denton’s emotion and sharing his excitement, found the aircraft’s key and pushed a stand alongside the plane so they could climb inside.

There was an electronics box mounted on the left side of the aircraft (part of the fuselage) that recorded signals from various scientific equipment connected throughout the airplane. Electrical panels that powered scientific equipment were still there. All the navigation electronics stood in place, as Denton had left them.

Gone were scientific meters and gauges in the cockpit, as well as the inboard, 500-gallon fuel tank that they relied on for long ocean crossings. “It was probably good that it was gone,” he said. “It was a bit of a disaster waiting to happen.”

Denton couldn’t help but remember some of the wilder flights aboard the C-54. “Depending on who you talk to in aviation, flying as low as 50 feet off the deck (water) in the middle of the Indian Ocean, 600 miles from nowhere, was being very bold and reckless,” he said. “But for veteran pilots of WHOI, it was all in a day’s work. Not that we weren’t nervous about it, but it seemed like the thing to do at the time. In retrospect, 30 years later, it seems a little crazy.”

Tracking down the plane’s history

Discovering the plane, he said, was like finding a lost brother or sister, or reuniting with a college buddy. “Naturally,” Denton said, “I wanted to know how it had spent the last 27 years.”

Denton began with a call to a former navigator on the plane, Hal Merry. Merry had a pilot’s license and access to Federal Aviation Authority records.

“Turns out my old friend the plane had had a real colorful history after leaving WHOI,” Denton said.

After storage in Arizona, the plane was sold to a private company in Texas. It then ended up in South America, where it was used to smuggle 9,820 pounds of marijuana into South Carolina. The six smugglers were caught, and the arresting sheriff was then empowered to sell the plane.

The plane’s next owner leased it to the U.S. Forest Service. “They painted it brown, strapped a 2,000 gallon tank underneath it, and turned it into a water bomber to fight forest fires,” Denton said.

A short time later, the Forest Service swapped the plane for a newer type of aircraft, and the plane was donated to the Aerospace Museum of California, where it has been on display ever since. Museum officials say they have plans to restore the plane to show how it was used for oceanographic research, but currently they lack funding.

Meanwhile, Denton continues to monitor the plane’s future. “I lost track of it once,” he said, “and don’t want that to happen again.”

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

Ed Denton, who retired from WHOI in 1995, was hired three decades earlier to transform a former military plane into a flying oceanographic research machine, tailoring it for scientists’ needs. Decades after it had been taken from service at WHOI, he found the plane completely by chance while visiting a California museum. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Ed Denton, who retired from WHOI in 1995, was hired three decades earlier to transform a former military plane into a flying oceanographic research machine, tailoring it for scientists’ needs. Decades after it had been taken from service at WHOI, he found the plane completely by chance while visiting a California museum. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- Members of the C-54 Skymaster aircraft's last flight crew while at WHOI included (from left) pilot Len Halverson, co-pilot Jack Cornell, navigator Hal Merry, engineer Bill Brown, flight mechanic Lee Russell, and radio officer Frank Mathews. (Photo by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Archives)

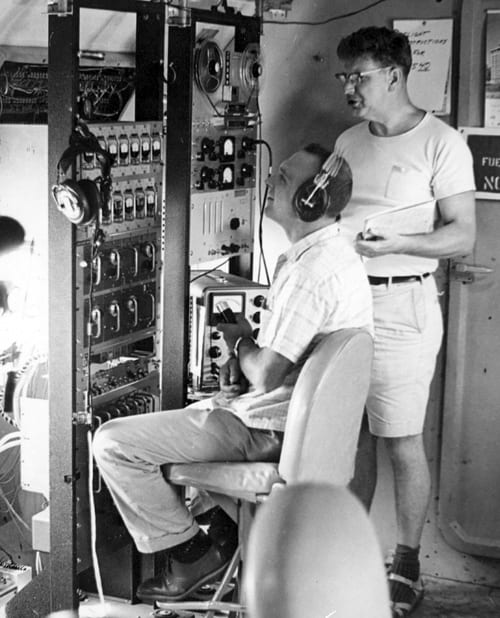

In 1964, while flying over the Indian Ocean, engineer Ed Denton (seated) and WHOI scientist Andy Bunker monitored records of scientific and atmospheric information aboard the C-54 airplane, including temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction, the aircraft's speed, and compass bearings. All the information was recorded on analog tape for further analyses back at WHOI.

(Photo by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Archives)- When Denton rediscovered the plane at the Aerospace Museum of California, it had been painted brown while in use by the U.S. Forest Service. Denton found out that after the plane left WHOI, it had had "a real colorful history," including drug smuggling. He is now encouraging restoration of the plane to show how it was used for oceanographic research. (Photo courtesy of Ed Denton)

Related Articles

- How WHOI helped win World War II

- Learning to see through cloudy waters

- Are warming Alaskan Arctic waters a new toxic algal hotspot?

- 5 essential ocean-climate technologies

- A curious robot is poised to rapidly expand reef research

- A new way of “seeing” offshore wind power cables

- New Techniques Open Window into Anatomy of Mollusks

- The Deep-See Peers into the Depths

- Up in the Sky!