Solving climate challenges, one innovation at a time

WHOI researchers report progress on projects funded by the Ocean Climate Innovation Accelerator

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Last March, five groups of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution scientists received almost one million dollars in shared funding to develop more precise estimates of the causes and impacts of global climate change. During the past year, they have been building and testing prototype instruments, developing innovative laboratory techniques, and holding collaborative workshops supported by the Ocean and Climate Innovation Accelerator (OCIA), a jointly-managed, multi-year consortium between WHOI and the Massachusetts-based semiconductor company Analog Devices, Inc. (ADI).

A grab-and-go device that records carbon changes in coastal water

Tiny marine algae called phytoplankton not only provide food for larger sea life, but also remove carbon dioxide from the ocean - and ultimately the atmosphere. As phytoplankton die, they sink into the deep ocean. Scientists don’t yet have a full picture of how this biomass is transported and transformed at depth, a process that includes conversion of the organisms back to carbon dioxide.

“Understanding how much, and how fast, this biomass is converted is what CRITTR was designed to do,” said WHOI marine chemist Matt Long, who is working with co-principal investigator and marine chemist Benjamin Van Mooy on the development of CRITTR, the Continuous Reconnaissance In-situ Twilight zone Tiny Respirometer.

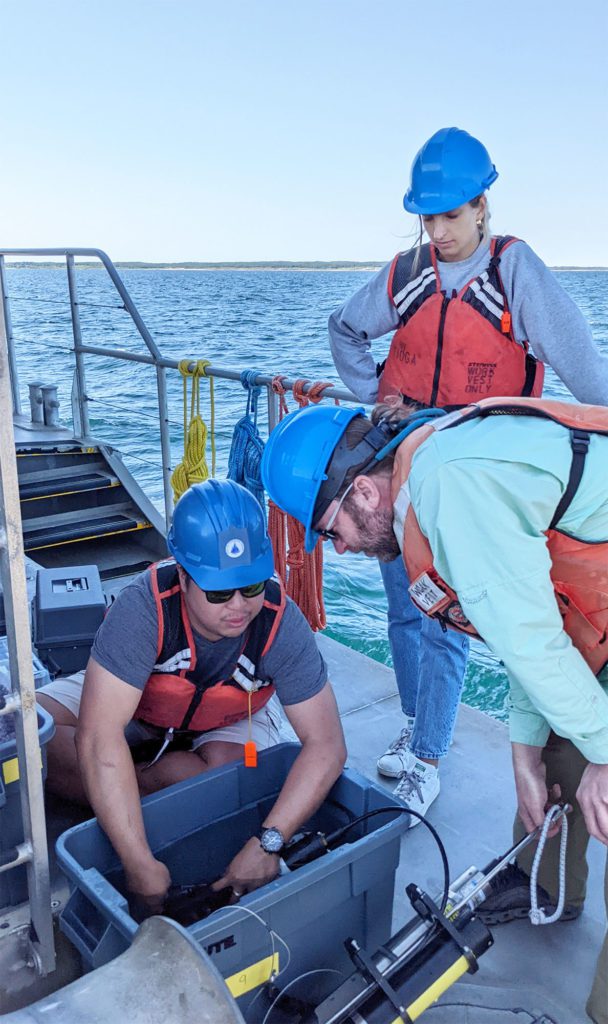

In July, 2022, using the WHOI coastal research vessel Tioga, Matt Long (right center), along with research assistant Solomon Chen (left) and WHOI summer student fellow Natalia Wierzbicki, tested two CRITTR prototypes in coastal Massachusetts. This spring they plan to deploy CRITTR during a Pacific research cruise to Oregon’s continental shelf. (Photo by Benjamin Van Mooy, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Designed to be low-cost, low-power, and portable (it’s small enough to fit in a backpack), CRITTR attaches to gliders, moorings, and underwater vehicles to record changes in seawater carbon concentration in different marine areas over time. It measures carbon flux at “twilight zone” depths of up to 1,000 meters (3,280 feet). It can also collect a variety of oceanographic data, including dissolved oxygen, temperature, and light levels.

The device uses commercially-available sensors and pumping components that are coupled to a reaction chamber about the size of a shot glass to determine the rates of metabolism, or breakdown, of dead phytoplankton in the water. Depending on the scientists’ needs, the measurements can be automatically repeated over periods of weeks or months.

In the fall of 2022, the design phase included three-dimensional printing of the device’s main components, designing custom electronics, determining light emitting diode (LED) intensity and flashing rate, miniaturizing and pressure compensating of the pumping system, and conducting initial field trials. Long also combatted the nuisance of biofouling (the accumulation of algae, plants, or small animals on wet surfaces) in the device’s reaction chamber by adapting the latest ultraviolet LED technology. He calls this progress “a major technological leap that enables long-term operation of the device.”

Finding a better way to track iron, a key to the growth of marine life

Phytoplankton are tiny plant-like organisms that form the base of the ocean food chain and play key role in Earth’s climate. Like humans, phytoplankton need and use the critical element iron in their diet to grow.

“Without iron, people become anemic,” said WHOI marine chemist Tristan Horner. “Scientists are still learning what this means for phytoplankton, which require iron to harvest energy from sunlight.”

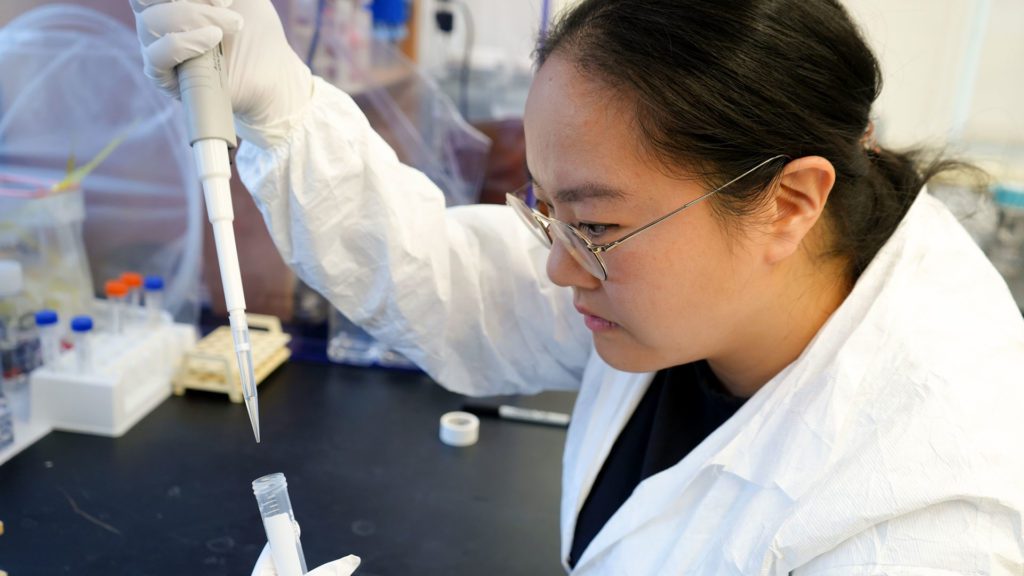

The goal of Horner’s project with marine chemist Mak Saito is to conduct iron isotope experiments on an upcoming research cruise to better measure the response of phytoplankton to iron additions, after refining their techniques through controlled experiments in labs.

Specifically, they intend to use iron-57 as a marker to trace the incorporation of iron within phytoplankton communities. Because much of the iron in these experiments will come from the marker isotope, it will be possible to attribute and track resultant growth by seeing how much iron is taken up and what cells are actually doing with it. This will provide an important step for tracking iron’s influence on biogeochemical processes by focusing on the fate of iron within complex marine systems.

They began their data collection last April, 2023, with a 37-day expedition in the Pacific Ocean, starting in Costa Rica and heading south past the Galapagos Islands before returning north. The cruise, which included two equator crossings, visited one of several ocean biomes that scientists think are iron limited.

“The resident phytoplankton could grow more, but they can’t because they need more iron,” Horner said. This makes this region ideal to study how phytoplankton communities respond to the addition of iron.

“We’ll try to answer: how much is taken up? Who is taking it up? What are cells doing with it?”

Since November, 2022, postdoctoral investigator and marine chemist Ichiko Sugiyama, an expert in the study of iron mineral reactivity in seawater, has worked with Tristan Horner and Mak Saito to prepare for their spring research cruise in the Pacific. One goal is to determine the best type of bottles for water samples; the sensitivity to iron requires immaculately clean bottles to avoid contamination. (Photo by Peter Crockford, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Sprucing up a system for collecting information on climate-critical gases

The boundary between the atmosphere and the ocean surface, known as the air-sea interface, is one of Earth’s most physically and chemically-active environments. Over hundreds of miles, the atmosphere sets the ocean in motion and drives the exchange of climate-critical gases such as carbon dioxide, particularly over upwelling regions and phytoplankton blooms.

Scientist James Edson’s marine research career at WHOI has focused on this critical space, and the device he is building is designed to directly measure the exchange, or flux, of carbon dioxide across the air-sea interface. His goal, along with WHOI scientist colleague Seth Zippel, is to develop a device that measures the average air-sea carbon dioxide concentration difference in this interface. It will compliment an existing system, informally known as the Carbon Dioxide Flux System, perated by marine chemist Aleck Wang on the WHOI research vessel Neil Armstrong.

They eventually hope to replicate the carbon dioxide flux and concentration systems on other oceanographic research vessels globally to expand the breadth of their climate research.

On a research vessel in the Indian Ocean, WHOI senior scientist James Edson installed an observation system to investigate the exchange of heat, mass, momentum, and moisture across the air-sea interface. He is developing a similar system for the WHOI-operated research vessel Neil Armstrong to measure the exchange of carbon dioxide. (Photo by Chris Fairall, NOAA)

Toward this goal, in the past year Edson has purchased several key pieces of equipment, including motion sensors and a sonic anemometer to determine wind speed. Working together, these instruments help to provide more accurate measurements of carbon dioxide exchange by correcting for the motion of the ship. He has also set up and tested an infrared gas analyzer, which is the device that measures the high frequency carbon dioxide fluctuations in the atmosphere. Finally, he purchased a dryer that removes the water vapor from air samples entering the analyzer to reduce moisture contamination as well as a “vortex sample inlet,” which helps eliminate sea spray that further contaminates the optics.

All of these improvements help to improve sampling accuracy, Edson said. “We’re coming up with new tricks to make things work more efficiently.”

In November, Edson’s talk on “blue carbon” (organic carbon that is captured and stored by the oceans and coastal ecosystems) at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Egypt (COP27) included a description of this project, which gained the attention of two marine research laboratories in the United Kingdom.

“The exchange of ideas and learning from each other is key to the ongoing climate discussion,” he said.

A low-cost, high-accuracy sensor for measuring ocean acidity

As humans increase levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, there is more carbon dioxide dissolving in the ocean. With that comes an increase in acidity, which scientists have measured for decades by monitoring pH levels in seawater.

Sensors exist to track ocean pH in different coastal areas, but historically it has been a tough parameter to measure accurately as some sensors are difficult to calibrate and may drift, said WHOI marine chemist Jennie Rheuban. She hopes to combat this with a unique new instrument and a wider community of partners.

“We are trying to use inexpensive components to build a reliable, easy-to-deploy sensor that will provide high-quality and trustworthy data,” Rheuban said.

This fall and winter, she and collaborators Aleck Wang and Glen Gawarkiewicz were pleased to develop a proof-of-concept sensor, including electronics, with early results showing a high enough precision (to the third decimal) to be considered nearly “a climate-quality pH measurement,” Rheuban said.

WHOI-MIT Joint Program student Jonathan Pfeifer (left) has been working with the project’s lead funding agency, ADI, to engineer and test electrical components that may be useful for a critical optical sensor on the instrument. He is part of the project team with Jennie Rheban (center) and Aleck Wang. (Photo by Kate Morkeski, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The team has also spurred relationships with others who will be key to the program’s success: commercial fishermen. A workshop funded by the WHOI Ocean Carbon and Biogeochemistry Office in late January, 2023 brought 80 participants to WHOI, including members of the New England fishing industry.

“They were central to the success of this workshop as they are the ones who will actually deploy the sensors from their vessels,” such as attaching sensors to lobster pots or trawling gear, Rheuban said. Fishermen will also benefit from the scientific data collected; they will be able to add accurate seawater pH information to the data they collect, providing a clearer image of the waters where they work.

After extensive instrument testing in the lab this spring and summer, and with the development of the needed wireless communication device to transmit collected data, Rheuban said they plan to test a deployable prototype instrument that may be used in depths of up to nearly 700 feet (200 meters). By fall, she anticipates that partnering fishermen will be testing a prototype instrument on their vessels in coastal New England waters.

A 10-year-old idea to collect climate data comes to life

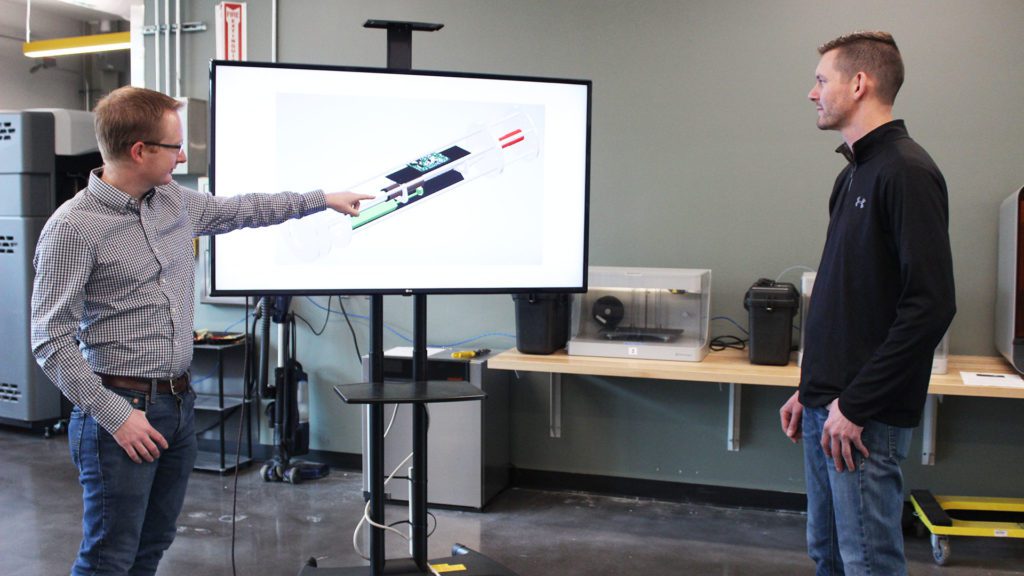

More than a decade ago, WHOI engineer Paul Fucile began thinking about how to power undersea profiling robots primarily from natural resources in the ocean environment, such as through solar or wave energy. When the call came for projects that continuously monitor critical metrics related to ocean conditions, including the collection of data related to carbon and climate change, he found the timing perfect to begin pushing his idea forward.

“It’s an opportunity to develop a lower-cost, longer-lasting robotic observer for extended missions that would have the capability to ‘self-heal,’” or recover from power deficits before they are potentially lost at sea. This also provides uninterrupted data collection, Fucile said.

With a robotic design in hand this spring, including a new controller board and electro-mechanical laboratory test fixture, Fucile and collaborators Robert Todd (left) and Patrick Deane are constructing components using the DunkWorks rapid prototyping facility at WHOI. This supports the instrument design testing and creation prior to deployment in a marine environment. (Photo by Paul Fucile, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The study of carbon in the ocean is made possible by the ongoing collection of temperature, salinity, currents, and biogeochemical characteristics, enabled by robots that work at sea for weeks, months, and years at a time. Operational limits in robots mean that scientists may miss capturing critical phenomena, such as the spring phytoplankton bloom, or that robots may be lost if their power supply fails before they surface.

“What we are doing is designing a new methodology for managing an ocean robot’s dive cycle energy,” Fucile said. During the past year, embracing years of experience from legacy designs, he and collaborator Robert Todd, a physical oceanographer at WHOI, have worked to develop new electronics architecture, energy storage, and circuit board design that makes their robots and robotic platforms less vulnerable to failure.