Should We Inject Carbon Dioxide into the Deep Ocean?

Study finds that some seafloor life may be harmed by high CO2 levels

One proposed strategy to offset rising levels of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere is to capture carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil-fuel-burning power plants and pump them into the ocean depths. Under the pressure of the deep sea, the CO2 would remain sequestered, proponents say—out of the atmosphere, out of sight, and out of mind.

But some tiny but critical denizens of the seafloor might be out of luck.

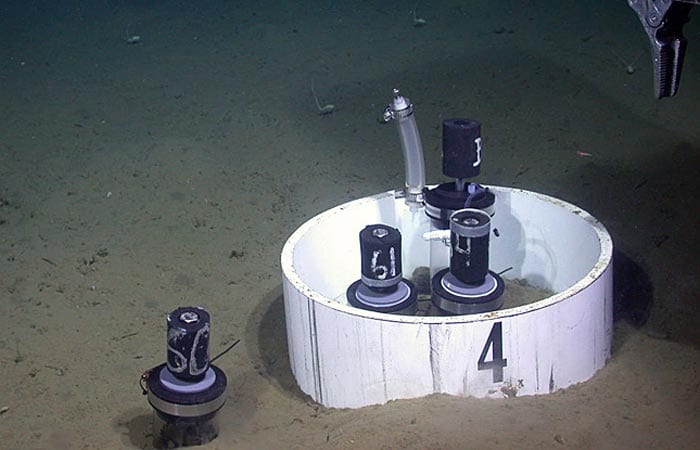

Joan Bernhard, a geobiologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and colleagues at Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) investigated how one proposed geoengineering technique—direct injection of CO2—might affect deep-sea life. Below a certain depth, the gas would form a dense mixture called a hydrate. Scientists think it would remain in depressions in the seafloor, not mixing with upper water layers and returning to the atmosphere.

In experiments they conducted on the seafloor of Monterey Bay off California, they found that some organisms survived exposure to high concentrations of CO2, but others were killed.The researchers published their results in the November 2009 issue of the journal Global Change Biology.

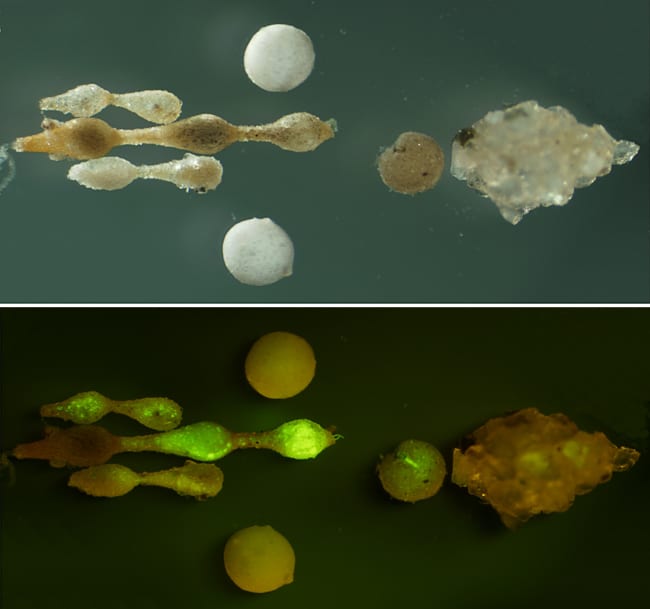

Bernhard studies the ecology and biogeochemistry of some of the ocean’s smallest inhabitants: single-celled organisms called foraminifera, which play a central role in the marine food web. The research team—Bernhard and Victoria Starczak at WHOI and MBARI colleagues James Barry and Kurt Buck—used a remotely operated deep-sea vehicle to push specially made cylinders into the seafloor mud and injected pure CO2 hydrate directly into them. After a few weeks, they also injected a fluorescent dye that labels live cells, but not dead ones.

“We found that foraminifera react [to injected CO2] in two ways—some did not appear affected in the slightest, but others are just gone,” Bernhard said.

The lack of green fluorescence in some species of foraminifera that make their protective coverings (called “tests”) out of calcium carbonate showed that they had not survived. But other foraminiferal species that make coverings of protein and sand still had a green glow.

The explanation? Higher concentrations of CO2 in waters make them more acidic, creating more hydrogen ions that bind with carbonates. That leaves fewer carbonates available for carbonate-forming (or “calcifying”) foraminifera to make their tests.

“It’s not doomsday for some species, but for others it may be,” Bernhard said. “If we’re serious about pumping CO2 to seafloor, we need to think about it. The seafloor is one of the biggest habitats on the planet.”

Bernhard and WHOI colleagues, geochemist Dan McCorkle and postdoctoral investigator Anna McIntyre-Wressnig, have done similar experiments on foraminifera with photosynthetic symbionts living on coral reefs at shallower depths, which are also threatened by increasing CO2 levels in the ocean due to the atmospheric CO2 rise caused by human activities. They are presently analyzing that data and hope to secure more funds to conduct further studies at sites where CO2 naturally vents from the seafloor to reveal more about how the smallest sea life will cope with changing and challenging climate and ocean conditions.

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Joan Bernhard (green jacket), of WHOI's Geology and Geophysics Department, and Kurt Buck of Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) carefully remove cores of seafloor sediment from the MBARI robotic vehicle Tiburon. Bernhard and colleagues injected carbon dioxide hydrate directly into cylinders pushed into the deep sea floor sediment and incubated them in place for a month to learn whether benthic single-celled organisms called foraminifera could survive the high-CO2, high-acidity method of carbon capture and sequestration known as "direct injection of CO2." (Photo by Erin Ricketts, University of California, Santa Barbara)

- Paired microscope images of deep-sea foraminifera—species that do not secrete calcium carbonate to make their shells—reveal that some cells survived extremely high levels of CO2 directly injected over the sediments they inhabit. The image on top shows individuals seen under a microscope using transmitted light. On the bottom, after specimens are labeled with a stain, only the living specimens emit green fluorescence. In the experiment, no calcareous (calcium carbonate-forming) foraminifera survived after CO2 hydrate was injected onto the sediments in which they live. (Photos by Joan Bernhard, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- To Tag a Squid

- How Do Corals Build Their Skeletons?

- Searching for ‘Super Reefs’

- Coral Crusader

- Hidden Battles on the Reefs

- Is Ocean Acidification Affecting Squid?

- Scallops Under Stress

- Swimming in Low-pH Seas

- Can Squid Abide Ocean’s Lower pH?

- Tiny. Ubiquitous. Vital. Delicate. Vulnerable.

- Sassy Scallops

- A Quest For Resilient Reefs

- Exhibit Spotlights Sea Butterflies

- Will More Acidic Oceans Be Noisier?

- The Once and Future Corals