Sharks Take ‘Tunnels’ into the Depths

Spiraling eddies offer conduits to food in the ocean twilight zone

As the Gulf Stream current curves away from North America and heads east across the Atlantic, it swirls at its edges. If one of these swirls is large enough, it will pinch off, sending a whirling pocket of water—more than 60 miles in diameter—spinning through the ocean like an underwater hurricane.

These swirling pockets, called eddies, may also be full of sharks.

No, this isn’t the plot of the next Sharknado movie. It’s a discovery by researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the University of Washington, who tracked the movements of several tagged great white sharks. They found that white sharks in the open ocean seem to seek out eddies for a surprising reason: The eddies offer a beeline to a banquet of food.

The Gulf Stream can spin off both warm- and cold-water eddies, and surprisingly, the sharks seem to have a preference. The warmer eddies are spawned when the Gulf Stream snakes farther northward, drawing warm water up from the Sargasso Sea. When the eddy spins away from the current, it traps that warm water in its center. But because that water is typically low in nutrients, these eddies aren’t thought to contain much life.

“The paradigm is that they’re like these ocean deserts,” said Camrin Braun, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography and co-author of the new study published in May 2018 in Scientific Reports.

Cold-water eddies are just the opposite. “They trap cold, nutrient-rich water from north of the Gulf Stream,” Braun said. “They’re anomalously cold and anomalously productive.” The extra nutrients can fuel enough phytoplankton growth to make these eddies visible from space.

So it might seem logical that when adult white sharks leave the seal-filled waters of coastal New England and head for the open ocean, they might seek out these whirling blobs of cold water, where phytoplankton at the base of the food chain are blooming. But apparently not. To the scientists’ surprise, the sharks spent most of their time in the warmer eddies.

Playing tag with sharks

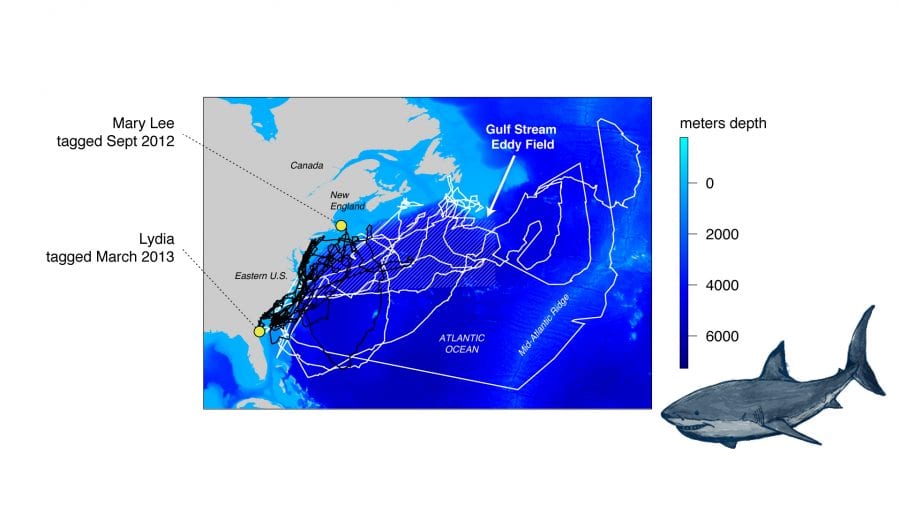

The research team followed two mature white sharks. Mary Lee, 16 feet long and 3,460 pounds, was tagged off the coast of Cape Cod in September 2012. Lydia, slightly smaller at 14.5 feet and just under one ton, was tagged off Jacksonville, Florida, in March 2013. (Their trackers have likely reached the end of their five-year lifespan, but both sharks still maintain active twitter accounts: @RockStarLydia and @MaryLeeShark.)

Lydia gained some notoriety as the first white shark to be tracked crossing the Atlantic, while Mary Lee tended to stay a little closer to the coast. Both demonstrated the unexpected preference for warm-water eddies, but it was Lydia, equipped with a second, specialized tag recording her depth, who hinted at a possible explanation.

Both sharks had SPOT tags, an acronym for Smart Position or Temperature. When the sharks came to the surface, the SPOT tags reported their position to a network of satellites.

Lydia, however, carried a second tag called a PSAT (Pop-up Satellite Archival Transmitting tag), which could record the depth and temperature of the water around her every five minutes. After six months, this tag released from her dorsal fin and bobbed to the surface to broadcast the data it recorded. All that accumulated information allowed the scientists to reconstruct her vertical movements as she swam through the eddies and paint a picture of her behavior.

“She made daily dives—spent a ton of time at the four hundred- to eight hundred-meter range,” Braun said.

What was she looking for in the depths?

“To be a shark that big, you’ve got to eat a decent amount,” Braun said. “And if you’re in the open ocean, where are you going to get a lot of food? The only place I can think of is in the deep ocean.”

About 656 feet down into the ocean—roughly two Statues of Liberty deep—the light grows dim. This is the upper boundary of the mesopelagic zone, which extends 3,280 feet deep before the ocean grows completely dark. There isn’t enough light for photosynthetic plankton to grow in this area of perpetual twilight, but that doesn’t mean it’s empty. In fact, the mesopelagic is one of the most abundant places around. Research suggests there may be more fish biomass in this area than in all the rest of the ocean.

It’s a great place for a shark like Lydia to eat her fill. But it’s also cold.

White sharks are endothermic. Like us, their bodies need to stay at a higher temperature than the water around them to function properly. It takes energy for sharks to create body heat, but it allows them to swim in the quick bursts they need to catch their prey and to digest more efficiently. It’s a good trade-off. But swimming in cold water for too long can throw off this balance, causing the shark to expend more and more energy to keep warm.

The warm eddies may provide a solution. “These eddies spin downward and inject warm water deeper into the ocean,” Braun said. For white sharks trying to grab a meal, it’s an efficient way to save energy. The eddies act “sort of like highways of warm water that might help connect them from the surface to farther down in the ocean.”

In search of a meal

Lydia dove in both warm- and cold-water eddies, but she stayed down for longer when the water was warm. She also made most of her dives while the sun was up, when animals that live in the mesopelagic zone remain in the deep, dark depths to avoid predation. At night, when those same species migrate to the surface to feed under cover of darkness, she made fewer dives, seeming to follow the food.

Still, a lot of questions remain unanswered. Scientists have yet to successfully document white sharks eating in the mesopelagic or determine why adult white sharks move offshore in the first place. But Braun says they aren’t alone in taking advantage of these warm-water eddies. He is currently working on a study tracking blue sharks, and his preliminary results show a similar behavior.

“We see this across at least a couple different species, where they’re using these eddies more than we might expect,” he said.

Which means these eddies, acting as conduits into the deep ocean, might be vital to the survival of these large predators.

“If these animals are indeed diving into the mesopelagic for foraging, which we think they are,” Braun said, “we don’t understand how much they might rely on that. Is it ten percent? Then maybe it’s not a big deal. Is it eighty percent? Then that’s pretty important for sustaining, say, a white shark population.”

Support for this research was provided by the WHOI Ocean Life Institute, OCEARCH, NASA, and the National Science Foundation.

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

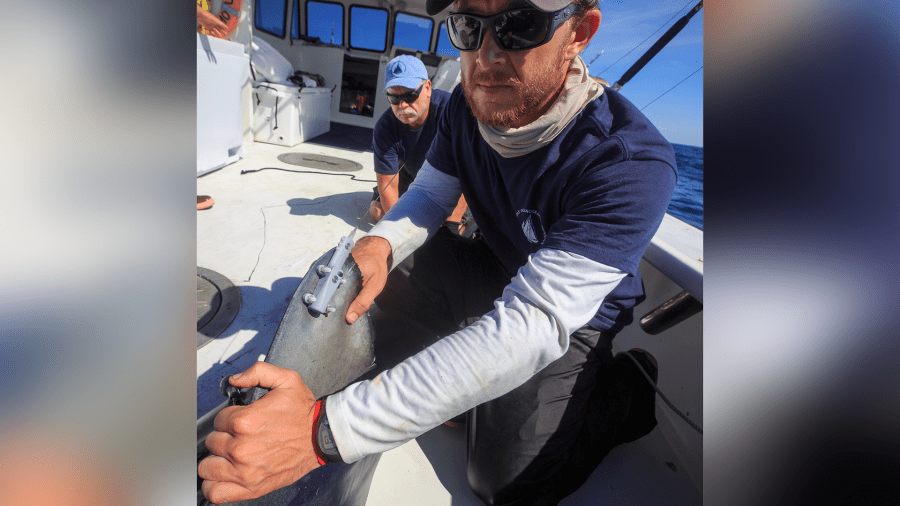

- Camrin Braun, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in oceanography, prepares to release a recently tagged blue shark off Cape Cod. Braun uses the data from these tags to figure out sharks' movements and behavior once they’re out of sight. (Courtesy of Tane Sinclair-Taylor)

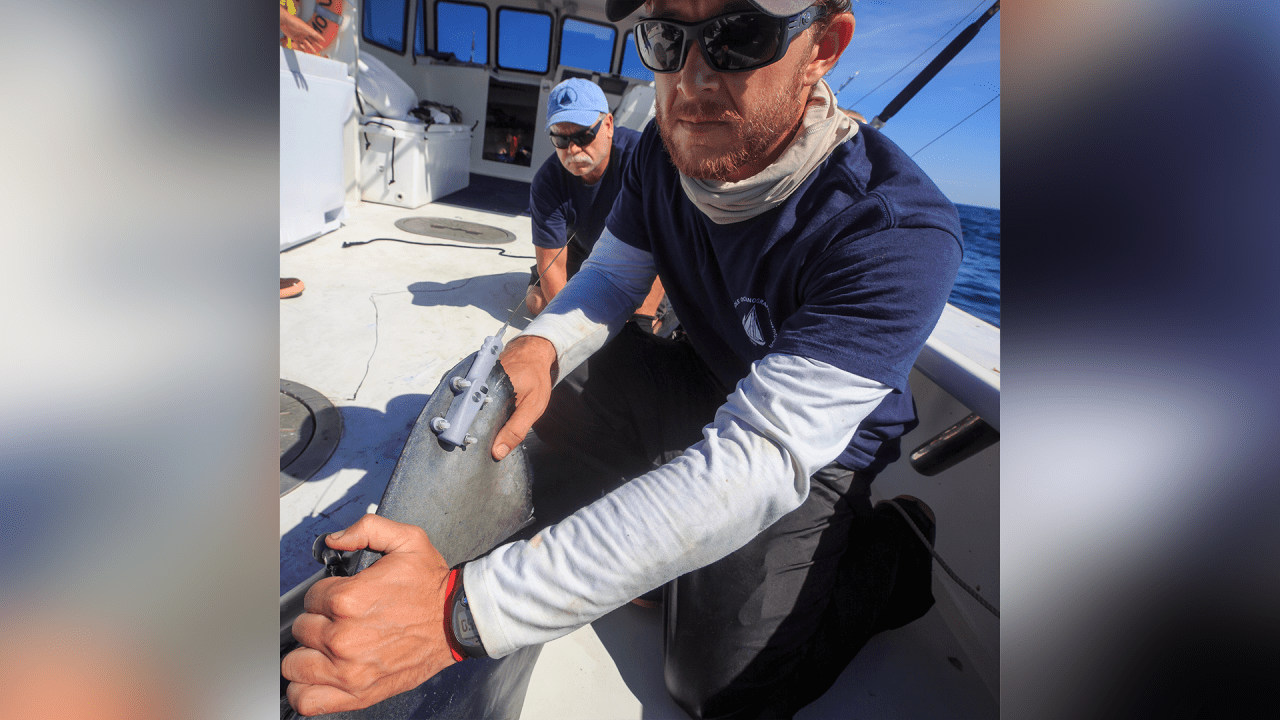

- OCEARCH researchers attached two tags to Lydia’s dorsal fin. The blue tag is a SPOT (Smart Position Or Temperature) tag, which reported her location via satellite when her dorsal fin breaks the surface. The tag’s lifespan is about five years. The orange tag is a PSAT (Pop-up Satellite Archival Transmitting) tag, which recorded the depth and temperature of the water around Lydia every five minutes. The tag released from Lydia’s fin after six months, floated to the surface, and transmitted its data via satellite. The combined tag data allowed researchers at WHOI to observe how Lydia dove through eddies to reach deeper waters. (OCEARCH/Rob Snow)

- Data from tagged white sharks such as Lydia give scientists a window into the movements and behaviors of these animals, which can help inform conservation and management decisions to protect the species. (OCEARCH/Rob Snow)

This map shows the tracks recorded by tags on two great white sharks: Mary Lee, tagged in September 2012, and Lydia, tagged in March 2013. Sharks can swim hundreds of miles in a day. Lydia was tracked for 4.5 years, and she the first white shark tracked crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Mary Lee also swam thousands of miles over the four years tracked here, but she preferred to stay in the western Atlantic.

(Camrin Braun/Natalie Renier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- Behind the blast

- Sonic Sharks

- Tracking big fish at fine scales

- Hope in fossilized fish bits

- A cascade of life

- As illegal fishing rages on, is there any hope on the horizon?

- Casting a (long) line to the twilight zone food web

- Wilmington’s shark tooth divers can thank the last ice age for their treasure trove

- Edie Widder: A light in the darkness

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Gulf Stream Sea Surface Currents and Temperatures The warm water of the Gulf Stream current ripples and swirls as it heads west across the Atlantic Ocean. These meanders can turn into massive spiraling eddies that spin back toward the eastern coast of the United States. New research by WHOI scientists has shown that sharks use these eddies to dive into the depths to find food.

- Diving in Eddies Camrin Braun, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program, created this animation showing the movement of a blue sharked tagged in October 2015. The tags on this blue shark recorded not only its horizontal movements but also the depths to which it dove and the temperature of the water around it. The shark dove deeper and stayed down longer in warmer water created by Gulf Stream eddies.

- Shark Tales from Oceanus magazine

- Following the Eddies Camrin Braun, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program, created this animation from data from a blue shark tagged in October 2015. You can see how the shark followed warm-water Gulf Stream eddies.

- The Secret Lives of Sharks A video on Camrin Braun

- An Ocean That's No Longer Wild An interview on apex marine predators with WHOI biologist Simon Thorrold

- Global Shark Tracker OCEARCH

- WHOI Fish Ecology Lab

- WHOI-MIT Joint Program in Oceanography