Meet the Sentry Team: Justin Fujii

A research engineer on autonomous reconnaissance and adapting the vehicle to new tasks

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

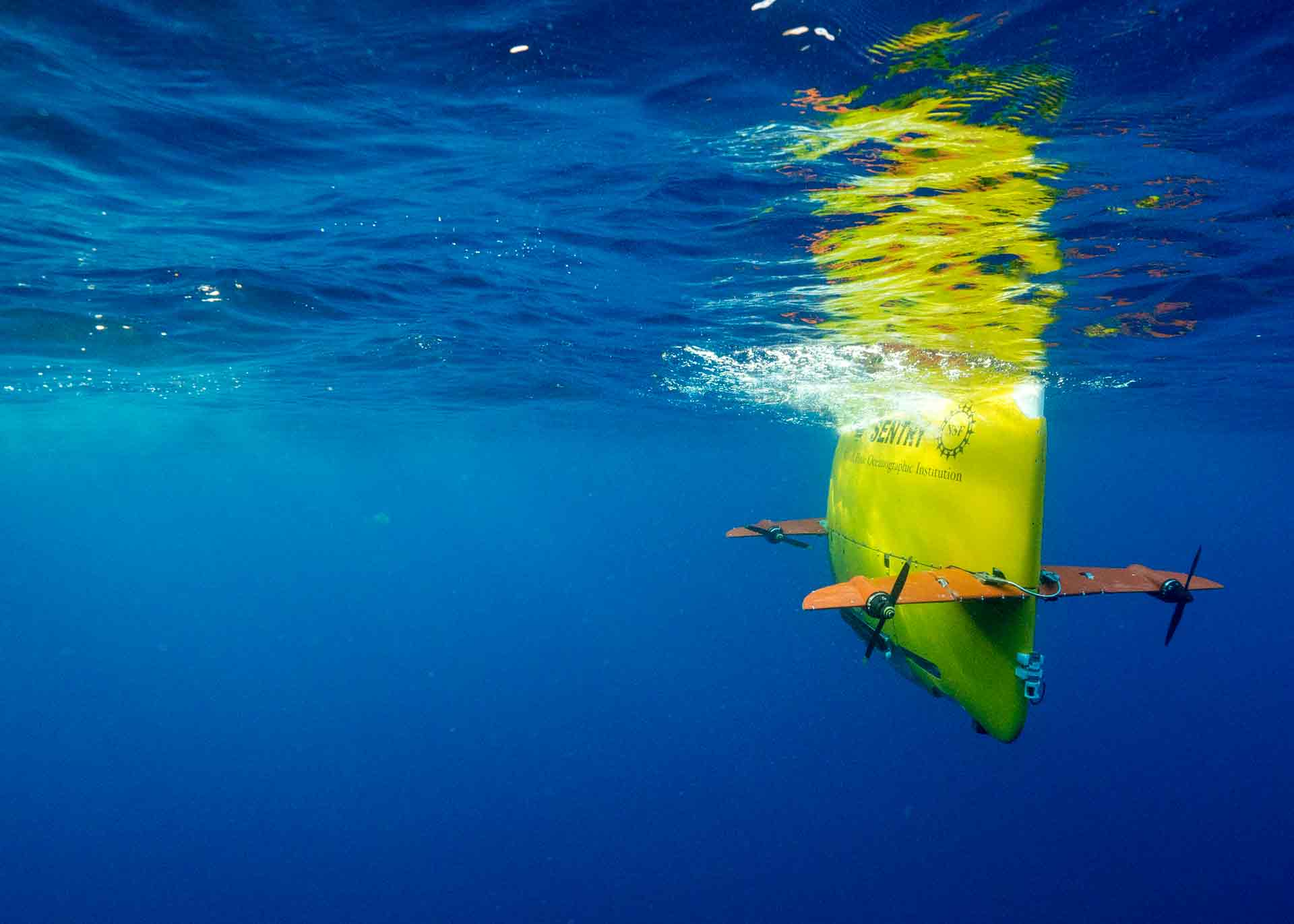

Justin Fujii is the lead mechanic and operation lead for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Sentry and an occasional expedition leader. Recently promoted to research engineer, Fujii has been with the Sentry Group for eleven years. Over that time, the Sentry Group has maintained a reputation for running a reliable vehicle that consistently performs the mapping and surveying tasks it was designed to do. Fujii is part of a team that adapts the vehicle to perform new tasks dreamed up by its scientific users.

(Luis Lamar © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Oceanus: What does Sentry do?

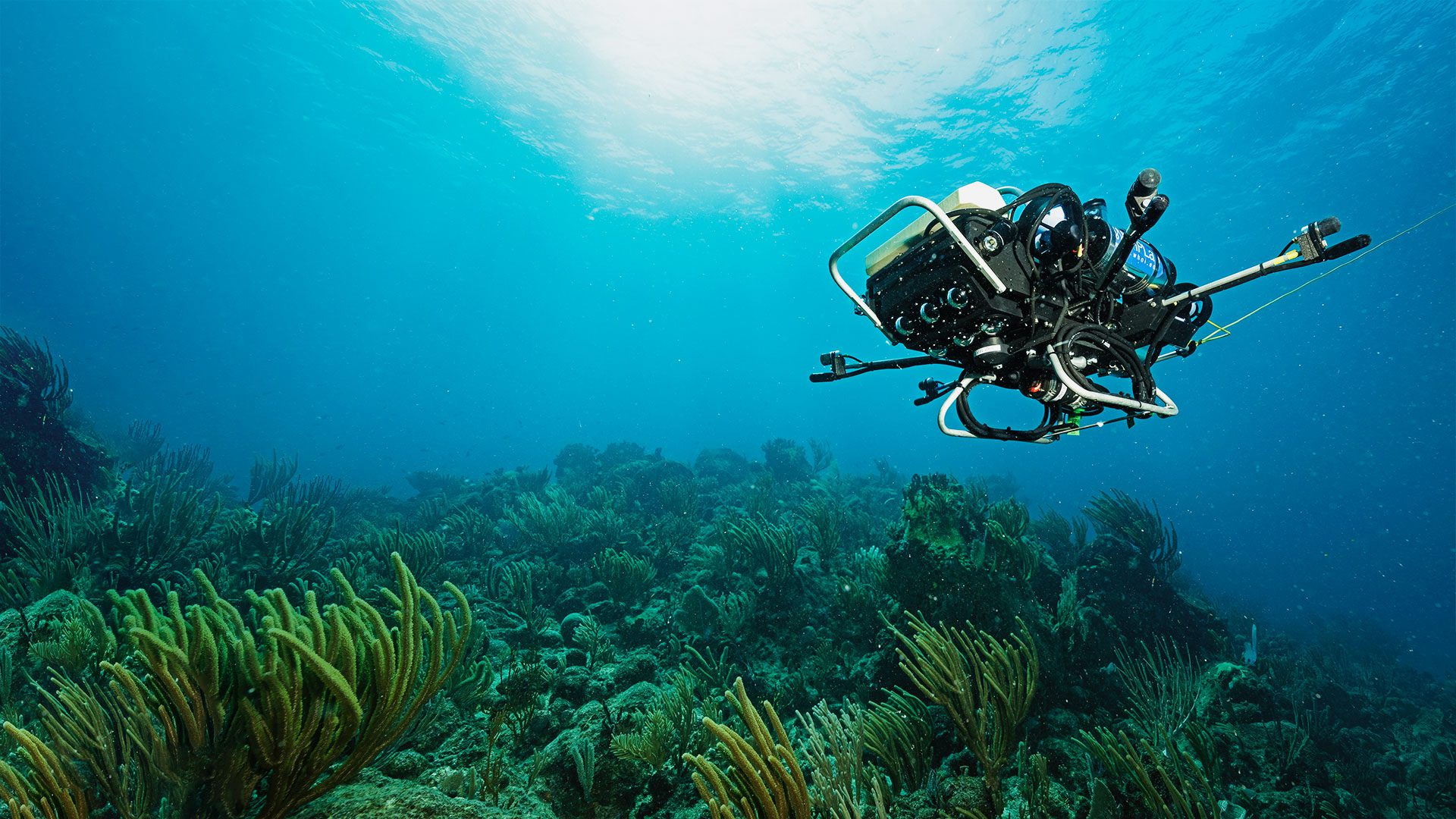

Fujii: Sentry is an autonomous underwater vehicle that can dive up to 6,000 meters deep (19,685 feet or 3.7 miles). It can cover a very large area very quickly without any kind of piloting, so you program it and away it goes—kind of like a Roomba. It is a nice asset to have in conjunction with remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason or human occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin. Sentry does the reconnaissance mission and then the ROV or submersible can go out and take pictures and collect samples.

We are also able to make a map from the information that comes back from a Sentry mission. A ship can get about 50-70 (165-230 feet) meter resolution mapping of the ocean floor, and Sentry can get resolution down to the centimeter.

Oceanus: How have Sentry’s capabilities changed over the time you've worked on it?

Fujii: When I started, it was able to make maps and do camera work. Now it does water sampling and larval sampling. We just did a cruise where we strapped methane sensors on it. It still works as it was designed to, but it has proved to be a stable platform to carry sensors as scientists have more ideas about how we could use it.

Oceanus: Did you ever expect to work on deep-sea vehicles?

Fujii: I studied to be an aerospace engineer. And I didn’t even know about oceanography when I was an undergraduate. A lot of the concepts are similar but different. Pressure is on the outside of the vehicle instead of the inside. And strength of weight is still important, but not as important as it is for aerospace applications. It’s ok for things to be heavy, which is also kind of weird compared to aerospace. In aerospace you want everything super light and strong and the ocean it’s like: “Yeah 3,000 pounds is ok.”

Oceanus: Does being at sea prompt new engineering ideas?

Fujii: A lot of cool things come out of being at sea. Sometimes, when I am waiting for the vehicle to come back on deck, I can go down a rabbit hole of what might be possible. But in general, I have an operational focus, and all my design is geared towards making Sentry work at sea and being able to fix it.

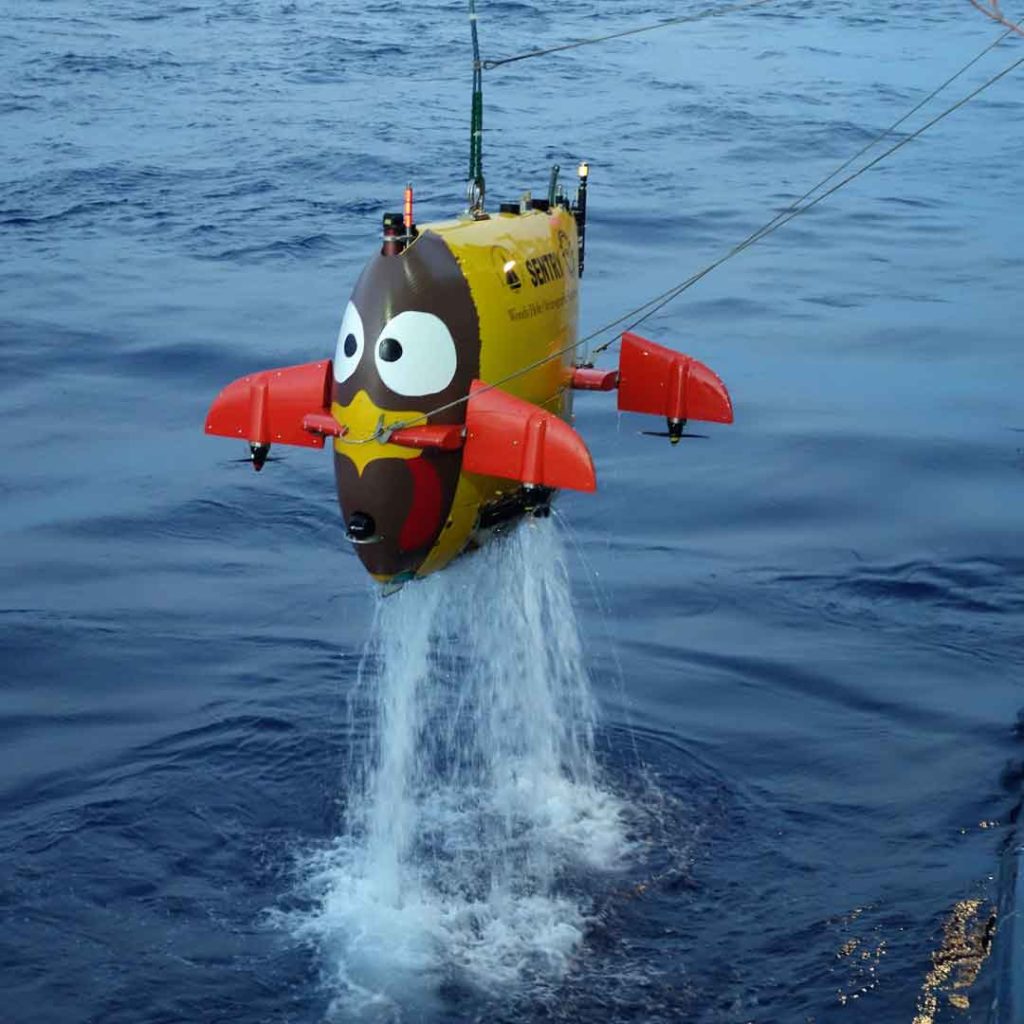

Oceanus: Tell us about the many “faces” of Sentry. How did that start?

Fujii: It was originally the idea of the chief mate on the R/V Thompson on a 2011 cruise when I had just started. She had made a face with scary eyes for Sentry long ago and suggested we do it again. And then it kind of caught on that Sentry gets a face. Now it's the immediate question as soon as I get on the ship: what's the face going to be?

I'll kind of sketch it out with like a dry erase marker and then I use electrical tape as the lines, and then I'll trim it to length and fill it in. There's a lot of excitement around the faces of Sentry and I’ve been trying to expand it more and have the scientists and other engineers do it too.