‘Seasonal Pump’ Moves Water Between Ocean and Aquifers

Seawater is drawn underground in winter and flows into ocean in summer

Knee-deep in water, WHOI hydrologist Ann Mulligan was working in Waquoit Bay on Cape Cod, investigating fresh groundwater flowing into the coastal ocean. Across the beach, she spied Holly Michael and Charles Harvey of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who were examining salty and brackish water flowing underground. Thus began a collaboration that has cleared up a mystery of why so much salty water emerges from aquifers into the coastal ocean.

The researchers discovered a counterintuitive seasonal pumping system at work: Groundwater mostly flows out to sea in mid-summer, when conditions in Massachusetts are driest and underground water supplies would seem to be at their lowest level. Conversely, great volumes of salt water are drawn landward from the ocean in winter to fill aquifers, which you would think would be filled by winter rain and snow percolating downward.

The findings were published in the Aug. 25 issue of the journal Nature.

Scientists have known for some time that the groundwater discharging into the ocean from aquifers can be salty, fresh, or a brackish mixture of the two. But how does salt water get into the fresh aquifers? Scientists know that seawater seeps inland—via tidal action, waves lapping on the beach, and other forces. But none of those processes moves enough ocean water inland to account for all of the salty water flowing outward.

Michael, Mulligan, and Harvey measured the flow of water in Waquoit Bay’s subterranean mixing bowl. They used seepage meters to measure the rate of groundwater flow into the bay during summer, and piezometers (which measure pressure) to determine the flow during winter when the surface was frozen. The measurements indicate that groundwater flows into the bay during summer, and bay water flows into the aquifer during winter.

The team used mathematical models to show that it can take several months until winter rain and snow can seep down through the layers of soil, sand, and rock. As a result, seawater is drawn into aquifers during winter until fresh water arrives. As fresh water reaches the aquifers in spring and summer, the water table slowly rises and reaches a threshold where momentum tips and forces water—now fresh and salty—to flow back toward the sea.

Mulligan notes that the inflowing seawater can acquire a lot of dissolved nutrients, contaminants, and trace elements from the ground. When it flows back out in summer, it may carry a substantial amount of those nutrients into coastal waters—at just the time of year to feed blooms of marine plants. Environmental experts know that nutrients running off land surfaces and through fresh groundwater contribute to algae blooms and to eutrophication—the deadening of coastal waters by overgrowth of plants that deplete oxygen. The new research points to salty underground waters as another potentially significant nutrient-loading source.

Mulligan and Harvey plan additional fieldwork in Waquoit Bay and hope to extend their studies to Florida to see if this natural, seasonal pumping system also occurs there. Mulligan and WHOI Engineering Assistant Alan Gardner also received a grant from the WHOI Coastal Ocean Institute to create a differential pressure logger, a new tool for detecting which way water flows between aquifers and ocean surface water. With that information, Mulligan can test the theory that seasonal pumping of nutrients from underground sources is playing a role in coastal eutrophication.

The National Science Foundation and the WHOI Coastal Ocean Institute funded this research.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- WHOI Assistant Scientist Ann Mulligan examines a data logger that has been lowered into a well in Waquoit Bay, Mass. The probe measures the conductivity, temperature, and water level in the well.

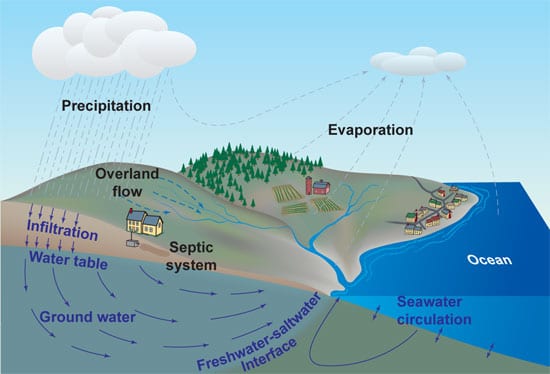

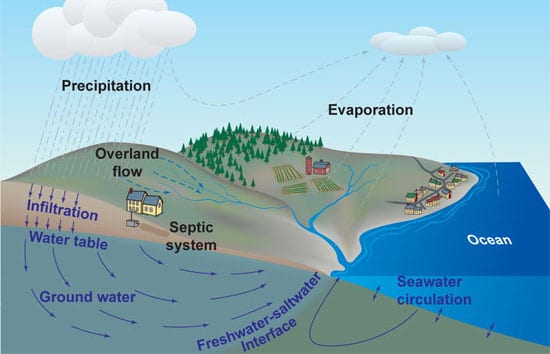

- This schematic shows the hydrologic (water) cycle near the coast. Water precipitates out of and evaporates into the atmosphere. It gets taken up by plants, flows into streams, or infiltrates the ground and recharges aquifers. Underground water flows from inland locations to lakes, streams, or coastal waters. On the seaward side, denser salt water enters sediments and establishes equilibrium with fresh groundwater. Tides and mixing along the freshwater-saltwater interface results in seawater circulation through the sediments.

- Ann Mulligan lowers a manual water level meter into a groundwater well near Waquoit Bay. Researchers measure the water level and chemical composition of groundwater to detect whether it is flowing landward or seaward.