Scuba Gear and Origami

A conversation with diving safety officer Terry Rioux

Terry Rioux has lived the life aquatic. He took a scuba diving course in college in 1967 and has been diving ever since. He’s lost track of how many dives he did when he was in the Navy, but since 1980, when he became diving safety officer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), he has logged (meticulously) 2,579 dives and 67,938 minutes under water.

Rioux inherited the job from WHOI’s first dive officer Dave Owen, who began the WHOI dive program in 1953. Since then, some 500 scientists, graduate students, engineers, and technicians have been trained—or tested and certified, if previously trained elsewhere—to dive to conduct their research. Rioux is responsible for reviewing and enforcing diving safety regulations, training and certifying divers, approving dive plans and equipment for scientific projects, and maintaining diving equipment.

“Terry has trained and influenced an entire generation of WHOI divers,” said David Fisichella, manager of WHOI’s Shipboard Scientific Services Group, which encompasses the diving program. “In his thirty years of service he set a standard of safety that will be be the benchmark for all future DSO’s (Diving Safety Officers) here at the institution.”

On April 1, Rioux and his wife Maggie, a long-time librarian at WHOI (whom he met at a scuba-instructor training course in 1980), are both retiring.

Where did you grow up?

I’m a local guy. I was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, raised across the Acushnet River in Fairhaven, which as the seagull flies, is only about 14 miles across Buzzards Bay from here.

My father was a commercial fisherman for 35 years. He’d go on 10-day trips out to Georges Bank or the Grand Banks, and then be home for four days, and then out again. It was a really tough life, and every time there was a Nor’easter or a hurricane, my mother would worry.

Did you ever go out fishing with your father?

I thought about it for a little while, but my mother was absolutely adamant that I not go into that line of work. Fishing is a very difficult life and one of the most hazardous occupations in the country.

Your chosen profession isn’t exactly without risk.

Let’s face it, diving is an adventure sport. It’s an environment for which we are not adapted. We use technology to visit this realm. You never, ever reduce the risk to zero. So there’s a need for people to be trained to go into that environment and do work. We have fairly stringent rules so that people can come back and do it again another day. The scientific diving community has had an admirable safety record.

How did you get started as a scuba diver?

I belong to the generation that saw the original films of Jacques Cousteau and also [the television series] Sea Hunt with Mike Nelson every week doing all his heroic things.

I was a biology major at Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute [now the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth]. I saw an advert for a scuba course at the old YMCA in New Bedford and thought, “That’d be kind of fun.”

Then when I graduated from college, I got this letter from Uncle Sam that started off, “Greetings.” So I said, “Hmm, well, I just don’t want to get drafted and end up in Vietnam. I think I’ll just join the Navy.” The opportunity came to go to diving school, and I took it. About a year later, there I was, heading off for Cam Ranh Bay, as a marine mammal handler.

What did you do in Vietnam?

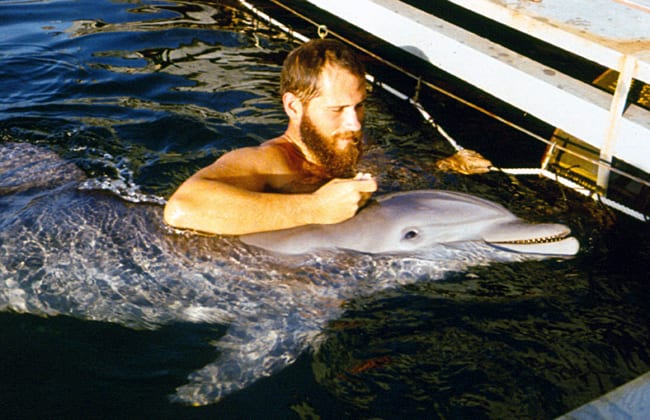

I was part of the military detachment testing out a new system using porpoises to defend supply ships from enemy swimmers who would come in and lay mines on the ships. Our job was to utilize the trainability, intelligence, and extraordinary sonar capabilities of the porpoises to detect and nullify the swimmer.

How did that work?

It was a secret program, but they recently declassified it a few years ago. They would put a special device on the porpoises’ rostrums with a spring-loaded little harpoon. The animal was trained to come and bump you, and the harpoon would come out and lodge in the enemy combatant with long wire and a strobe light, and then we’d go out and neutralize them. The system was never actually put to a real test.

Of course, we had to test the system. So us low-rated folks would be woken up in the middle of the night, and they would take us way the heck on the other side of this tropical lagoon and have us try to sneak up on the porpoises. Of course, they didn’t have the real thing when they bumped us [Laughs].

Then I got transferred to the USS Coucal. She was built to rescue and salvage submarines, should they become sunk. I was a hard-hat diver— the old copper “Mark V” diving helmets. A full generation hasn’t seen that equipment.

I’ve seen pictures of that old diving gear. What was it like?

You had to be fairly strong, because it was heavy, and it was not like the modern dry suits. The rig itself weighed about 190 pounds on the surface, when you include the lead-soled, leather shoes and the heavy-duty canvas-rubber diving dress, as they called it, the brass breastplate, the heavy-duty helmet, and the heavy weights. You needed all that weight, because you’re in kind of a human-shaped bag filled with air. The helmet was actually a big bubble. You’d have continuous flow of air coming through the helmet. It was very noisy, and it would damage your ears after awhile. You had to shout all the time to be heard.

Why do WHOI scientists need to dive, when they have sophisticated vehicles and subs for oceanographic research?

People really need to make firsthand observations. It’s really hard to chase, say, a fish around with an ROV [remotely operated vehicle]. In the past, you’d take nets and dredge them through the ocean and come up with whatever comes up on deck, but if you’re dealing with gelatinous zooplankton, you come up with goo. Whereas, when you actually are down there with these animals, you can see that they have some pretty complex behaviors. You can actually see them completely spread out, doing natural things.

Nowadays, most of our divers are engineers. They develop gadgets and test them right here at the dock to make sure it works before they take them out at sea. And divers rapidly and fairly inexpensively maintain instruments that are put in the water. I don’t know how you’d be able to do some of these jobs without diving.

What is the safety record of the WHOI dive program?

Well, we’ve had people get decompression sickness, but when you look at what actually happened, they have all been what they call “undeserved bends,” which means the divers were well within limits of safe diving. It’s just that, you know, humans are fairly fragile beings, and we’re going in an alien environment, and sometimes things happen, but it wasn’t because we did anything wrong.

What has been the biggest challenge of your job?

We have rules to try to rein in the enthusiasm, shall we say, of scientific divers. Sometimes, guys and gals chafe at the rules. It’s a juggling match between enabling your clientele and trying to be flexible to let them do their jobs, but also trying to enforce rules to prevent injuries. All these dive rules were written in blood, when you think of it.

There is a small but still significant risk every time you get in the water. You have to realize and accept that or else you don’t get in the water. And if you’re in the business for long enough and do enough dives, then sometimes your number can come up.

I tell my divers there’s three times during the diving career when they’re most at risk. The first is when they’re novices, and they’re still getting used to the environment physically and psychologically. The second is when they’ve been an active diver, but they haven’t done it in a long time. They might remember themselves as good divers, but they’re pretty rusty, so they have to come back and refresh their skills. But the third: Some of my divers who are really, really very experienced—they’ve done it a long time—sometimes you can get complacent, and you really have to guard against that. Sometimes really experienced divers get into trouble. Now that I’ve actually had my own injury, I know from a firsthand point of view what it feels like, and I would like not to have anyone else have to go through that.

Tell us about how you got “bent”?

It was on a dive that I have done probably a thousand times in the past. I was in my office, having my coffee, and one of my divers came in and needed to do a few more dives, and, of course, at the time, any time anyone wanted to do a dive, I was right there, just loved to dive. So we popped in the water off the dock and just kind of swam around. The water temperature was 53°F, a little chilly, but nothing that I hadn’t done. And the profile was well within the tables. We even did a nice slow ascent. I usually like to stop at 15 feet for three to five minutes, just as a safety factor, but it was chilly, and I only stopped for like 30 seconds to a minute, came up and developed symptoms in the shower. My legs didn’t work. So something happened on that dive—what, I don’t know. I just made a bubble, and it just happened to come out in my spinal cord. Having oxygen here, I was able to control it a little bit, and we went to the [recompression] chamber. But still it took a long while to come back. I was in the hospital for about a week.

Do you have to train divers for different kinds of conditions?

Our divers go pretty much anywhere in the world, from the Red Sea to Antarctica. We can do the training for all those right here in Woods Hole.

We can train for low visibility. The best visibility I’ve ever seen off the WHOI pier is about 30 feet. This past year we’ve had a lot of storms, and the visibility has been 2 to 3 feet, so it really trains the divers to be aware of where they are and what they’re doing and be able to come back to their exit point.

We also have a lot of current under the pier. We have an awful lot of boat activity. There’s fishing lines, and there’s all sorts of things in the water. So our divers are trained to be able to maneuver [amid obstacles]. They start off their diving careers really forced into dive safety.

We can do deep-water training. Right at the end of the WHOI pier, the water is 70 feet deep. It’s one of the very few areas in Cape Cod where you can actually get into deep water from the shore.

And we can do cold-water training. In certain years, wintertime temperatures off Woods Hole can approach temperatures off Antarctica.

You have also dived with disabled people.

We have had in the past a group called the Moray Wheels dive with us. It was formed for and by folks with various physical challenges. They’ve dived here at the pier, and we’ve actually gone with them to various Caribbean areas. We’ve dived with folks who were quadriplegics, paraplegics, amputees. They’re always buddied with an able-bodied buddy, and they do very well under water.

What are some amazing animals you’ve seen on dives?

Oh, I’ve seen sea snakes. I’ve seen lots of sharks. I’ve pretty much touched or encountered just about anything you can think about. Put my hand on a crown-of-thorns starfish, snorkeled into a little cavern where the walls were lined with turkey fish—you know, those fish with the big filamentous rays that are all poisonous.

Is there anything you wish you’d seen that you never did?

Nowadays, I’m very jealous of my students. You know, I spend all this time and effort in the pool and in open water with them, and then a few months later, they go to the Red Sea and don’t take me. [Laughs.] Highly jealous of that. Kelton McMahon and Leah Houghton found their way into a project tagging whale sharks in the Red Sea. I’ve never even seen a whale shark, and these guys go out and have some nice shots taken of them tagging whale sharks.

Do you have other hobbies besides diving?

When I was on the Coucal in 1971 in Sasebo, Japan, I saw this book, in English, about paper folding, and I thought, “Yeah, it’s going to take us two weeks to get back across the Pacific.” After I had gone through the book and done the models, only one really stuck in my mind, a traditional frog. My long-suffering wife finally said, “Would you learn something else?” So there’s a group called Origami USA, headquartered at the Museum of Natural History in New York City, and they have conventions. We decided to go, I started to acquire books and things.

It’s a fun little hobby. My mom was an artistic person. She was a housewife, but she had many artistic interests. She did ceramics and silver working and stained-glass work, and quite a few other crafts like that. I got into crafts because of her.

It’s a lot of fun when you go out to restaurants, because you can make origami out of dollar bills. Let me show you an example [looks through his wallet]. I usually have a couple. Ah, here we go. This is a very popular one—a little teddy bear. We leave these [with wait staff], and we tell ’em, “If they keep it in their wallet and don’t spend it, they’ll always have money.”

—Interviews by Frank Taylor and Kate Madin. Erich Horgan was interviewed by Heather Handley Goldstone. Photos accompanying audio interviews courtesy of of Terry Rioux, Maggie Rioux, Larry Madin, Cathy Cetta, and Erich Horgan. Edited by Lonny Lippsett and Kate Madin.

What is decompression sickness?

While underwater, divers are under pressure, which is measured in atmospheres. At the surface, the pressure is 1 atmosphere, but divers are subject to 1 additional atmosphere for every 33 feet they descend. The air they breathe is about 21% oxygen and about 78% nitrogen, and increased pressure causes their blood and tissues to absorb more of those gases. For example, at 99 feet, tissues have four times the nitrogen that they have at the surface. When divers ascend, the nitrogen concentration in their tissues is higher than in the air they are breathing, said Craig Cook, medical editor for Sport Diver Magazine and a physician who has served as diving medical officer on many expeditions. The excess nitrogen comes out of their tissues into their blood and lungs, and is eliminated by breathing. If the diver stays down too long or comes up too rapidly, the nitrogen comes out too fast and can form bubbles in the tissues and blood, instead of being breathed out. The diver may develop symptoms of decompression sickness (“the bends”), which can range from mild to severe—from rashes and joint pain to paralysis and death.

To treat the bends, divers are put in a hyperbaric (recompression) chamber, breathing pure oxygen under pressure simulating diving depths, to shrink the bubbles and accelerate the elimination of nitrogen.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- In the 1970s Rioux trained to be a Navy hard-hat diver, which required a sealed copper helmet, lead boots, and more heavy gear. “The whole rig weighed about 190 lb on the surface,” he said. “Nowadays, a full generation hasn’t seen that equipment.” (Photo courtesy of Terry Rioux, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A Navy diver during the Vietnam war, Rioux worked for a few months in a program training dolphins to use their intelligence and sonar capabilities to locate enemy swimmers approaching docked ships. (Photo courtesy of Terry Rioux, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Diving Safety Officer Terry Rioux’s office overflows with material collected over the years—partly inherited from his predecessor—documenting scientific diving from its infancy in the late 1950s though the development of modern equipment and regulations, and including records of every logged scientific dive made by a WHOI diver. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Rioux trains both new and experienced divers for scientific scuba diving and WHOI certification. Here, in a local pool, Rioux (right) conducts a class that includes Joint Program student Kelton McMahon (left), who now uses scuba diving to study coral reef fish and whale sharks in the Red Sea. (Photo by Margaret Rioux, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Maggie Rioux diving under the WHOI dock: “A scientific diver has to do, collect, or observe something, and it might not be in the best conditions,” Terry Rioux said. “People need to be trained to go into that environment, do their work, and come back safely. But we have a great area to train divers for many conditions.” For example, the average visibility under the WHOI dock is about 8 to 12 feet, and after storms, ”not so good—3 feet, 2 feet.” (Photo by Terry Rioux, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- How WHOI helped win World War II

- Seeding the future

- New underwater vehicles in development at WHOI

- Learning to see through cloudy waters

- Five marine animals that call shipwrecks home

- Go with the flow

- Navigating new waters

- For Ben Santer, the fingerprints of the climate crisis are very human

- The 10,000-foot view